"What's It Like There?": Desultory Notes on the Representation of Sarajevo

Jim HicksSmith College

james@transpan.it

© 2002 Jim Hicks.

All rights reserved.

- In order to begin, I'll have to confess: what follows here will be an essay in the early sense of the term (in other words, I have no idea whatsoever how it's going to come out).[1] I've decided, nonetheless, to make an effort to address--or at least avoid in a somewhat more professional manner--an issue which for me, in the five or so years that I've been visiting Sarajevo, just won't go away. The problem is that I continue to have no real answer to the question that my title poses, the question that, for understandable reasons, I'm asked on almost every occasion when someone finds out I've been spending time in postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina.

- To some extent, my lack of a well-considered response may be personal. I also have a great deal of trouble with word association games ("What's the first thing that comes to your mind when I say 'Bosnia'?"); invariably, what comes to my mind--no matter what the word is--is nothing. Faced with such questions, rather than "associate freely" (as if such a thing were possible!), I become increasingly embarrassed at not having a response, more or less in the way that insomniacs lie awake obsessed with their inability to sleep. On the other hand, such a reaction may be situational as well. Hannah Arendt long ago argued that there is essentially nothing to say about events which require our compassion. For Arendt, the problem with compassion is precisely that: it puts an end to all discussion, and hence, to any possibility for political remedy (53-110).[2] (There are, of course, other opinions about the relation between compassion and expression: Clarissa, La nouvelle Héloïse, and Uncle Tom's Cabin are all very long novels.)

- In any case, in conversations with friends, I found out quick enough that my problem couldn't easily be finessed through intellectualization. Like some character from a Woody Allen film, I tried to begin my (non)responses by describing my inability to describe, cleverly attributing this inability to my complete lack of adequate representational categories. My experience, in short, was "like" nothing in the least. And without adequate categories, some would argue, we may not even have the experience at all--"a blooming, buzzing confusion" is the phrase usually evoked in such contexts. Yet, for Walter Benjamin, experience itself--at least its truest, and increasingly rarest form--may in effect only come at times like these, where we lack all preparation.

- Friends, since they know you, can't be put off by such diversionary tactics, and, to be frank, I wasn't even satisfied myself with this non-answer. But then, at some point--I don't remember precisely when--I came up with an alternate strategy. I still began by describing my inability to describe, but now this ramble became only the preamble to my next gambit--telling a joke or two. The number, as well as the character, of the war-related jokes that I heard on my initial trip to Sarajevo no doubt prompted this idea. In retelling these jokes, I also eventually managed to convince myself that there was logic behind my strategem: where do such jokes come from, after all? why do people tell them? and wasn't the collective voice behind them more direct, more authentic, than anything that I myself might say? At one point, I even thought about compiling a Sarajevo Joke Book, a sort of exercise in contemporary folklore. One Bosnian who heard this idea from me commented, "Sure, everyone who comes here wants to do that."

- A couple of jokes, then. Here's one that nearly

everybody there knows:

Too quick? Lack the relevant history? (In case you don't already know, during the war, Bosnian Serbs dynamited the mosques in the towns they controlled; Banja Luka used to have many, including the celebrated fifteenth-century Ferhadija mosque, which is now a parking lot).[3] Let me try another one:[4]Q. How do they give directions in Banja Luka?

A. Turn left where the mosque used to be.

So you get the picture. Or at least some of the picture. Whatever these jokes are, they're certainly not timid. Part of their impact, no doubt, comes from the particular ways in which they violate our conventions and expectations. Take a look back at the image at the beginning of this essay. How does your sense of it change when I tell you that--although the site is in fact located in Sarajevo--it is not actually war-related? It's just an abandoned farmhouse, and it's looked more or less as it does here for as long as any of my Bosnian friends can remember.[5]Mujo is walking down the street, just out of the hospital after having his right arm amputated. He's depressed to the point of desperation, crying, talking to himself, thinking about suicide. He can't bear the thought of life without his arm. Suddenly he sees Suljo walking towards him, skipping and smiling. When he gets closer, Mujo sees that Suljo is actually laughing out loud. What is most amazing to Mujo is that Suljo is carrying on like this despite the fact that not just one, but both of his arms have been amputated.

So Mujo stops Suljo, who continues to snicker and smile. Mujo says, "Suljo, I don't understand you. I'm desperate, I'm even thinking about killing myself, all because I've had one arm amputated. You've had both your arms cut off and here you are smiling and laughing like an idiot. In your condition, how can you be so happy?"

Suljo replies, "Mujo, if you'd had both of your arms cut off, like I did, and your ass was itching like crazy, like mine is, you'd be laughing too."

- Actually, the first photo I took in Sarajevo was this one:

This was the view from the window of the Human Rights Coordination Center, in the Office of the High Representative, downtown Sarajevo, Maršala Tita Street, in early January, 1997. I like it--something about the perspective reminds me of Bruegel.[6] Given the stories about Sarajevans burning furniture and books in order to heat their homes, the sight of children sledding in this wooded urban park might surprise you. (It did me, which is probably why I took the photo.) Just above the park is the central police headquarters, used by the Bosnian military during the siege. The trees, in other words, were left as cover--anyone silly enough to try and cut one down would probably have been shot. A second park survived for similar reasons, and there is also still a beautiful, tree-lined avenue next to the river (and next to the former front line as well).

Figure 2 - My next photo is an exterior shot of the building from

which the sledding picture was taken:

I have a theory about this one. This is, or was, the headquarters of the Office of the High Representative (the international supervisory agency set up as part of the Dayton Accords, <http://www.ohr.int>). The High Representative has very extensive powers to enforce the implementation of the peace accords; among other things, OHR has designed Bosnia's new currency, license plates, and flag, and the High Rep has also dismissed a fairly large number of Bosnia's elected officials (including on two occasions, members of the Presidency). If you've seen Men in Black, the movie that's being advertised in this photo, you'll understand my suspicions: my guess is that the placement of this particular advertisement is meant as a comment on the internationals working just behind these curtains. There's certainly no cinema in this building, or anywhere close by, and, as far as I know, no other movie was ever advertised here.[7]

Figure 3 - My overall point so far, with the "farmhouse" photo as with the others, is fairly simple. Pictures don't speak for themselves, however much we may be predisposed to let them do so. But then neither do my Bosnian jokes: one thing that strikes me about the two cited here, besides their ruthlessness, is that they are both in some sense directed at the very group that is telling them. Much like Jewish anti-Semitic jokes, Bosnian humor has a long tradition of self-parody. The two amputees of my second joke are actually the stock characters, the fools, of Bosnian comedy (Mujo, by the way, is short for Mustafa, or Muhamed, and Suljo for Sulejman). A third character, Mujo's wife Fata (short for Fatima), also makes frequent appearances. But those jokes you don't want to hear.[8]

- You have no doubt been waiting to see a photo

like this:

Actually, I would go further than that. My guess is not only that you've been expecting to see a photo like this: if you followed the war in the former Yugoslavia at all, I imagine that, on some level, you've been waiting to see this very photo. This, of course, is the Oslobodjenje building, headquarters of the Sarajevan newpaper of the same name (which means "liberation" in English).[9] I haven't heard what, if anything, is planned for this building, but I wouldn't be surprised to see it left as it is now, as a war memorial of sorts. Which, once again, changes what it is that we're looking at, does it not? Is it event or emblem? In a certain sense, memorials may not be seen at all; to paraphrase Robert Musil, if you want to be absolutely certain that someone is forgotten by history, build them a statue.

Figure 4 - One more photo in this vein:

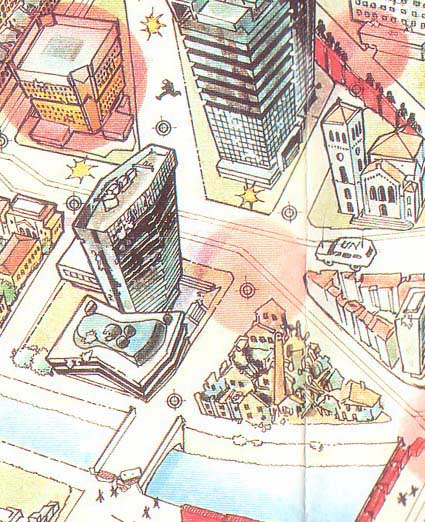

I reproduced this shot for two reasons. The photo shows a government office building in the foreground and the two UNIS skyscrapers in the background. What I mean to give you here--the academics among you--is a rather unique vantage point. The shot was taken from the balcony at the end of the hall on the fourth floor of the Filozofski Fakultet, right next to the English Department offices. (Does it make you feel at home?) My second reason is explained on the back of a map which the FAMA group--a local artists collective--did to commemorate the siege (<http://www.saray.net/SurvivalMap/Index.html>). It seems that Sarajevans had nicknamed these twin towers "Momo" and "Uzeir" after a popular pair of local comedians (their names mark them as members of two different cultural groups). According to FAMA, no one knew which tower was which, and so the Bosnian Serb army had to destroy them both. Such are the stories one hears.

Figure 5 - Time for another sort of story, I think.

This one is from Miljenko Jergovic, a journalist, novelist, and poet. Jergovic wrote for Oslobodjenje during the war, and he now writes for the Feral Tribune in Zagreb. The text of his that I will examine here is, in a sense, the titular story of his first published collection, Sarajevo Marlboro. The final scene of Jergovic's short story unwraps this pair of name-brands for his reader--but I'll get to that in a minute.[10] The tale itself, in contrast, is titled "Grob" ("The Grave"--for reasons unclear to me, his translator decided to retitle the story "The Gravedigger," i.e., "Grobar").

Figure 6 - When Jergovic chose his title, it is absolutely certain

that the grave he had in mind was not shown in this last photo. First of

all, it's not even the right graveyard. Second, this shot, if it were

published in Sarajevo today, might well appear to be Bosnian Muslim

propaganda. The tombstones in front, with their inscriptions

written in calligraphy said to be found only in Bosnia, are just the sort

of things used to send a "nationalist" message. (There are, of course,

items of this sort available for all of the so-called nationalist

parties. If it's old enough, and culturally specific enough, it will do.)

Nice photo, though.

Figure 7 - The story begins by asking us a question: "Know why you should never bury people in a valley?" (78). Jergovic's gravedigger, a Shakespearian character in more than one sense, goes on to answer the question with a story. He tells a tale of two lovers, and two deaths, related (in the original text) by means of a single long sentence, a conversational diatribe that twists and turns at least twice as often as the lives the story traces. In high school, Rasim and Mara fell in love (again, their names are markers), his father said no, and they ran away. Rasim's father eventually found them, but his son wouldn't come home alone; so the couple moved in but she wasn't allowed to leave the house by day. Eventually the father built them a home in another neighborhood, they married publicly at last, and then she died. (As the gravedigger comments, "[the dead] just happened to lose [their lives], the way some people lose a pinball [... after] having scored a hundred points a hundred times--you could have scored more, but... you didn't" [82].)[11] Rasim moved again, mourned by day and worked in his uncle's bakery at night, and, when WWII broke out, he joined the Ustaše (the Croatian fascists); then the war ended and the Partisans arrived, who jailed him and were planning to shoot him, at which time a certain Salamon Finci appeared and convinced them that, during the war, Rasim had helped five Jewish families escape through Italy. So Rasim was freed, but nothing changed, and he continued to mourn his wife until, one day, he too was found dead, facedown in a pile of bread dough, and was brought back to his father's house and buried "just here beneath the patch of grass you are standing on" (80).

- As told by the gravedigger (as opposed to the account you

just heard), this story is not only an answer to the opening question, it

is a demonstration of the answer. As the narration unfolds, it is filled,

in line after line, with gestures toward the neighborhoods, buildings, and

landmarks where the lives of Rasim and Mara are said to unfold. Its

refrain is "ono ti je Bistrik... ono ti je Širokaca... ono ti je Vrbanja"

(Roughly, "That's Bistrik for you," "That's Širokaca for you,"

etc.) In my last photo, the lower section of the Alifakovac cemetery

can just be seen on the upper left; like us, though from the other side,

the gravedigger looks down the Miljacka river with all of the Old City

before him. His story concluded, he points to Rasim's grave below his

feet and ends by commenting, with obvious satisfaction:

From this spot, it's possible for you to review and reflect on Rasim's whole life. Only thieves and children and people with something to hide get buried in valleys. There's no life left in the valleys--you can't see anything from down there. (Jergovic 64, translation modified)

- In an essay entitled "Dell'opaco," Italo Calvino has described how people can sometimes be imprinted with a particular topography of the imagination, just as goslings are imprinted with a maternal form. For Calvino, that topography was his native city of San Remo, with its rugged, mountainous coastline sloping sharply down to the west, opening out expansively toward the mist-covered sea. Jergovic's gravedigger carries a different template, but his principles are those of Calvino.

- And there may be more. As we are painstakingly shown,

Rasim's life, with and without Mara, stitches together most of old

Sarajevo, geographically and topographically (and hence, we may conclude,

socially and culturally as well). We are even told that Mara's distraught

husband "blamed each of the local districts... for her death" (79), and

that he responded by moving to Vrbanja. Now I don't know what Vrbanja

looked like before WWII, but I can show it to you on the FAMA Survival

Map.

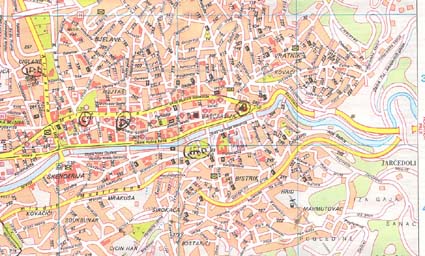

There it is, at the start of the modern city, where the Parliament building is, and where most major social protests in Sarajevo begin. It's also where, on April 6, 1992, Radovan Karadzic's men--from a position atop the Holiday Inn (the yellow building, circled in red)--started firing at a crowd of antiwar protesters. Serb paramilitaries had already killed one young student during similar demonstrations the previous day, on the bridge right at the bottom of the image. The bridge is also called Vrbanja.[12]

Figure 8 - However relevant such commentary may--or may not--be

to the Jergovic story, it still leaves unmentioned that narrative's

central connection to the essay at hand. As it turns out, about half of

"Grob" actually relates a second anecdote, one that speaks of the living

rather than the dead. Immediately after his comment that "There's no life

left in the valleys," the gravedigger begins telling a more recent tale,

one that recounts the unpleasant experience of being interviewed by an

American journalist:

The journalist claims that "he wants to know everything" (81); in order to respond to his questions, however, Jergovic's narrator has either to ask for clarifications or resist the terms in which the questions are put. Asked to speak indiscriminately of both the living and the dead, the gravedigger replies that such a task is impossible, "because the dead have their lives behind them while the living don't know what's just around the corner" (81); asked if he's sorry, after all his travels, to have "ended up" in besieged Sarajevo, the narrator corrects his interrogator, commenting that, "I didn't end up here. I was born here" (81). Then, when "the idiot" reporter asks if the gravedigger is ready to die now in Sarajevo, the latter replies, "I've thought up hundreds of ways to stay alive, and I like all of them" (82). Moreover, when the gravedigger does respond to the questions, his philosophizing appears to be of little interest: "I can tell that he doesn't understand or even care what I'm saying, but I don't take offense" (81).Perhaps he'd heard that I lived in California for a while, and had seen the world, spoke languages and knew important people. But now I was working as a gravedigger again, so perhaps he thought that I might be able to explain to him what had happened to the people of Sarajevo. (80)

- In short, Jergovic's second anecdote relates an account of failed communication. This failure, we should know, is a specific sort, one probably common in such interviews. The central difficulty involves what might even be a familiar trope of journalistic performance, if readers and viewers were sufficiently aware of the tricks of the trade. At the risk of losing my own audience, I'll venture to call this particular sleight of hand "Live Puppet Ventriloquism" (and I'm thinking here, analogically, of the "Live Organ Donors" scene from the Monty Python film, The Meaning of Life).

- As far as Balkanist writings go, the classic work for

illustrating this trope is, without a doubt, Robert D. Kaplan's

Balkan Ghosts. For those not familar with this work, let me cite

Kaplan's thesis statement (a claim which, not by coincidence, is also a

perfect example of the figure in question). Here then, for your

information, is the essence of the Balkans, according to Kaplan:

The sentence that ends this quote makes its author's thesis explicit, yet it is ostensibly not the author speaking. Live Puppet Ventriloquism.This was a time-capsule world: a dim stage upon which people raged, spilled blood, experienced visions and ecstasies. Yet their expressions remained fixed and distant, like dusty statuary. "Here, we are completely submerged under our own histories," Luben Gotzev, Bulgaria's former Foreign Minister, told me. (xxi)

- In contrast, Jergovic's tale is meant to reveal the way that such shenanigans obstruct communication (rather than, like a chemical precipitant, giving evidence of otherwise invisible interactions). The gravedigger is extremely clear on this point. When the interview finally breaks down entirely, he comments, "I understand that he is researching the subject for his article, except he can't write the piece because he already knows what it's going to say" (82). The apparent paradox in this sentence's latter half (isn't it easier to write when we know what we will say?) is, in effect, a clever subversion of the sort of journalistic research to which its first half refers. What sort of "research" is it, after all, that aims at producing, from the lips of another, speech that you yourself have scripted? Live Puppet Ventriloquism.

- Unlike Jergovic's journalist, Kaplan is overtly and insistently conscious that he--or at least his American audience--may not yet possess the necessary script. Like Jergovic's gravedigger, moreover, Kaplan sees this issue as a problem of perspective, of obtaining the correct distance and vantage point. The very first lines of Kaplan's prologue summon up a relevant scene: the author has chosen an "awful, predawn hour to visit the monastery of Pec in 'Old Serbia'" (xix). Moreover, he comments, "I brought neither flashlight nor candle. Nothing focuses the will like blindness" (xix). There, while pondering the monastery's medieval frescoes, the author has his book-generating revelation. "Fleetingly, just as the darkness began to recede, I grasped what real struggle, desperation, and hatred are all about" (xx). We should also note that Kaplan opposes this knowledge--obtained as he "shivered and groped" (xix)--to the judgments typical of "a Western mind... a mind that, in Joseph Conrad's words, did 'not have an hereditary and personal knowledge of the means by which an historical autocracy represses ideas, guards its power, and defends its existence'" (xx). (A mind that is also, we may assume, comfortably installed in its favorite Western easy chair, reading Balkan Ghosts.)

- By the end of this prologue, Kaplan is capable of

answering the question that he himself posed only a few pages ago, the

same question which I borrowed as an epigraph for this essay. He pictures

himself again, this time while crossing the Austrian border with the

former Yugoslavia.

Needless to say, our Western mind turns quickly away from this scene of dirt, disease, and misogyny to look outside, only to find dirt, disease, and misogyny:The heating, even in the first-class compartments of the train, went off. The restaurant car was decoupled. The car that replaced it was only a stand-up zinc counter for beer, plum brandy, and foul cigarettes without filters. As more stops accumulated, men with grimy fingernails crowded the counter to drink and smoke. When not shouting at each other or slugging back alcohol, they worked their way quietly through pornographic magazines. (xxx)

[13]Snow beat upon the window. Black lignite fumes rose from brick and scrap-iron chimneys. The earth here had the harsh, exhausted face of a prostitute, cursing bitterly between coughs. The landscape of atrocities is easy to recognize... (xxxi)

- At last, increasingly fed up with his interviewer,

Jergovic's gravedigger finally shuts him up:

In other words, the American journalist is told that he, like Robert Venturi, ought to "learn from Las Vegas": anyone moving at that speed, with those sort of interests, anyone so obviously out of place, certainly shouldn't pretend to intimacy. "When you look at advertising billboards from fifty feet away, you don't have a clue what Sarajevo Marlboro is or isn't" (84). Telling the story of Rasim from a vantage point overlooking the city, or even reading into that story some significance which might still be of use for the living, is one thing. Reading the faces of strangers is certainly another.I tell him that he shouldn't gaze into people's faces so intently if he doesn't understand what he sees. Perhaps he should just look at things the way I used to look at neon signs in America, in order to get a rough idea of the country. (82)

- Or is it? An undeniable characteristic of the stories contained in Sarajevo Marlboro is that they often read like fables or parables. It is equally obvious that, unlike some fables or parables, the moral to these stories is anything but explicit. Capturing both qualities, the final scene of "Grob" will function as a synecdoche for the book as a whole. Having despaired of direct communication, Jergovic's gravedigger resorts once again to demonstration. He takes from his pocket an unmarked pack of cigarettes. He explains that Bosnia has no factory capable of printing brand names and logos. "I bet you think we're poor and unhappy because we don't even have any writing on our cigarettes" (83). Whether this particular journalist, in this instance, had this particular thought or not, it's safe to say that some journalist nearby did. If not about cigarette packs, about something.

- Having snared his opponent, the gravedigger moves in for the kill. He begins to undo the packet, ready to show that it does indeed contain printing, on the inside. Sometimes movie poster paper is used, sometimes soap boxes, sometimes other forms of advertisements. What's inside is, in the narrator's words, "always a surprise" (83). This time, however, hidden around the corner is a joke, one played on the gravedigger himself. In this particular case, the paper used was from the old Bosnian brand of Marlboros. Hidden inside the paper of this particular cigarette pack was the paper of a pack of cigarettes: Sarajevo Marlboros.

- The narrator comments:

Later on, I regretted that I ever opened my big mouth to the American. Why didn't I just say that we are an unhappy and unarmed people who are being killed by Chetnik beasts, and that we've all gone crazy with bereavement and grief. He could have written that down, and I wouldn't have ended up looking ridiculous in his eyes or in my own. (84)

- Time to sum up. Having at last recounted "Grob"'s final anecdote, I may now also be in a position to say something further about a contradiction, or at least a confusion, in my essay thus far. How exactly does the gravedigger's favorite point of view, the template of his imagination, differ from that of Kaplan's "Western mind"? Both, it seems clear, are a product of distance, and both attempt to present their subjects by placing them on some sort of narrative map; furthermore, the explanations that both give are explicitly meant to be seen as products of those maps. It wouldn't be all that unfair to say, like Rasim, that Robert D. Kaplan blames "each of the local districts" for the tragic fates of its inhabitants. Given the unexpected, and self-defeating, result of the gravedigger's final demonstration, could it then be said that a Las Vegas blur is the only sort of vantage that remains?

- It seems to me that such a conclusion, or any such conclusion, is precisely what Sarajevo Marlboro resists. Let me offer some small bit of evidence, albeit indirect. Until the final paragraph of "Grob" (I checked), none of the three so-called "ethnic" or "national" labels occur, even once, in Jergovic's story. This is not to say, of course, that this is not a tale about cultural difference--above, you will recall, I argued that it is precisely that. If forced to summarize, I'd probably say that Jergovic shows us culture as the product of many things and people as the product of many cultures: names, neighborhoods, war, family, all of these things--even "a brand of cigarettes developed by Philip Morris Inc. to suit the taste of Bosnian smokers" (83, emphasis added).

- One more comment. When the gravedigger points out, with great satisfaction, each key site in the life of a single Sarajevan, I am quite certain that I don't know what it is he's talking about. I myself never set foot in any part of the former Yugoslavia while it was still Yugoslavia, I never visited Sarajevo until after the war, and, although I read journalists, I don't plan to become one. You, in all likelihood, have never been to Sarajevo at all. Even so, you probably understand why some people wondered whether "Mara had in fact remained Mara, or had become Fatima" (79). Some people do worry about such things; in Jergovic's tale, however, we are also told that no one asks, and that Rasim doesn't tell. My point is quite simple. When we hear a litany of place names in a story about Sarajevo during the siege, just what does a given place, or even its name, mean to any given Sarajevan? How could we even ask?

- By way of closing, however, I will relate one last

anecdote of my own (a brief one, I promise). Actually, what I'd like to

do, even if only in virtual space, is to take you on a nice

little walk, first up above the gravedigger's cemetery (where it says

"Alifakovac"--just below the first sharp turn in the river) to a sort of

two-lane highway (the yellow road below the river), and then walking east

along the hillsides, following the Miljacka upstream--eventually taking

you right off the Sarajevo town map, I'm afraid.

I learned about this particular itinerary on my first trip to Sarajevo, from Leah Melnick, a close friend of my sister (and an inveterate flaneuse, I was told). That's when the following pictures were taken.

Figure 9

Click for a larger image - Walking down the highway, after fifteen minutes or so you

come to a tunnel (visible on the far right of the map above). You don't

want to go in the tunnel, not even in a car. Tunnels in Bosnia

don't have artificial lighting and they're usually full of water and

potholes (although these days at least they no longer have little

surprises like an IFOR tank at the other end).[14] In any case, Leah's

directions were clear--follow a little path, off to the right, up over the

tunnel. You should be a bit nervous about that, and, of course, you will

remember the rule: don't walk anywhere where many, many others haven't

already walked before you. Follow footprints. Otherwise, as the public

safety announcement tells you, it's not a question of "if," just

"when" (cf. <http://www.unicef.org/newsline/super.htm>). Here,

the path is in fact a very well-trodden path, and it leads

surprisingly soon into a small village, one that was hidden until now by

the curve of the hill in front of you. (And by me.) Here's a part of what

you find.

I haven't got anything to say about this one. Just look at it. And imagine, if you can. (I can't.) Then, as you continue to walk along the small, two-track path though the village, this is what you see.

Figure 10

And this is all you see.[15] And there's plenty more of it, above these houses too and in front of you along the path, as well.

Figure 11 - And then, at the very last house before your road starts

to wind around and down to the river, there's something different. A dog

barking. Not a friendly dog. Some movement and some noise in the back

corner of a yard.

It's not much of a house, not yet at least, but it's standing. And there's someone there, living there perhaps, working in the yard at the moment, probably cleaning up. I have no way of telling you how glad I was to see him.[16]

Figure 12 - After I followed the path down toward the river, I turned

back once more. Here's that shot as well:

Now then. Leah had mentioned that eventually I would come to a bridge, so that I would be able to get across the river and walk back along the other side. (This soon after the war, a bridge wasn't by any means a given). Here's the bridge:

Figure 13

The locals call this ancient monument, this sculpture, this testament to both place and time, The Goats' Bridge. Though I didn't know it then, it's traditionally thought of as the easternmost border of Sarajevo. So here's where we turn back, walking along the river back into town. What will greet us at this end of the city is, for a couple of reasons at least, a fitting conclusion to our (or at least my) cyberramble.

Figure 14

This, of course, is (or was) the National Library, first built as a city hall by the Austrians at the end of the nineteenth century. If the Oslobodjenje building has any competition in the category of de facto memorials to the Sarajevo siege, this would be it. Appropriately for us, Miljenko Jergovic ends his Sarajevo Marlboro collection with a piece entitled "The Library." Its final words are as follows:

Figure 15 The fate of the Sarajevo University Library, its famous city hall, whose books took a whole night and day to go up in flames, will be remembered as the fire to end all fires, a last mythical celebration of ash and dust. It happened, after a whistle and an explosion, almost exactly a year ago. Perhaps even the same date that you're reading this now. Gently stroke your books, dear strangers, and remember, they are dust. (154)

Figure 16

|

| Figure 1 |

"What does the earth look like in the places where people commit atrocities?"

-- Robert D. Kaplan, Balkan Ghosts

English and Comparative Literature

Smith College

james@transpan.it

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2002 JIM HICKS. READERS MAY USE

PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S.

COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED

INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

1. A shifty statement, for obvious reasons. The following text was first presented on April 21, 2001 as part of the "Visible Cities" session of the annual meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association, at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Given that it investigates public, and published, modes of representation, including my own, I think it best to present the paper here more or less "as is," or "as it was." With the exception of minor adjustments intended to ease the shift from oral to written, all elaborations, corrections, qualifications, commentaries, and other forms of more recent speculation on my part are given in italics.

The quote by Kaplan, presented here as epigraph, was not read at the conference, although I did, and do, feel that my analysis as a whole can be characterized as an attempt to understand how someone--and quite possibly anyone--could think (not to say publish) such a thought. If I have an answer to Kaplan's question, it would be, quite simply, "Home."

2. My summary of Arendt's argument is borrowed from Elizabeth Spelman's Fruits of Sorrow (62-8). Another important recent work, also responding to Arendt's views, is Luc Boltanski's La souffrance à distance (15-21).

3. This reference, for anyone following events in the region, is particularly loaded. As it turned out, a couple of weeks after the ACLA conference, a ceremony was held in Banja Luka to mark the beginning of this very mosque's reconstruction. The event was attended by various members of the international community, including the U.S. Ambassador. It was also attended by a well-organized, well-equipped mob of Bosnian Serb nationalists, who broke up the ceremony by stoning the officials and lighting buses on fire, fatally injuring at least one Bosnian Muslim man. For more information, see the Institute for War and Peace Reporting's "Balkan Reports," #245 and #258, by Gordana Katana (<http://www.iwpr.net>).

4. At Boulder, I had to cut the second joke to keep within (or at least close to) my allotted time.

5. This may be overstated. When I double-checked my story after the conference with another Sarajevan friend of mine, one who often goes rock-climbing near there, he agreed that the house was abandoned before the war, but added that it was also damaged significantly--the roof for example--during the war. My point in introducing the photo, and introducing the essay with the photo, was to evoke a certain ready response in my audience, one that is based on some fundamental assumptions. One such assumption is, of course, our belief that we know what we're looking at: "We've seen this kind of thing before." Also prevalent is our faith in the testimony of "experts."

6. Actually, the photo shown at the conference was somewhat different. Here various smudgy areas in the snow hide (poorly, I assume, since this is my first attempt at doctoring a photo) telephone and electricity wires, as well as a garbage can.

7. The question remains, however, just how far my knowledge goes. Again, on further inquiry, I found out that there was in fact a cinema--The Dubrovnik--in this building before the war and that, a year or so after this photo was taken, the space was again used to advertise a movie (in this case, of all things, Runaway Bride). Despite these ugly facts, I still like my joke; moreover, it still sounds, to my ear, sort of "Bosnian."

As in the previous note, I mean to call attention to the dogmatic character of the language used: e.g., "no other movie was ever". By now it should be evident that I don't really trust such statements, yet I nonetheless find myself drawn into making them--as if it somehow goes with the territory.

8. This section was also cut, mostly for lack of time.

9. The story of how the paper kept going throughout the siege is recorded in a book called Sarajevo Daily, by Tom Gjelten. The paper's editor-in-chief during the war, Kemal Kurspahic, has also published an account.

10. Actually I didn't. At the conference I decided, nonetheless, to leave in this reference to my original destination. The commentary on Jergovic's story has been extended in this version, and now does include some analysis, however brief, of the section alluded to here.

Ozren Kebo, in a war diary which rivals the achievements of Sarajevo

Marlboro, has commented on the branding of the Bosnian capital:

Anything blessed by the media acquires exchange value. The market is

blind to morality, to the fight between good and evil. This market begins

just behind the Serb trenches at Kiseljak. Once the media have managed to

make people sick of one product, something that they've robbed of its

tragic character, or its greatness, or whatever, that product becomes

nothing more than consumer goods. In Milan, on the 24th of December,

1993, I came across a porno video that was titled "Sarajevo." It was on

display in a black street vendor's stall. Here, in short, was the dirty

trick played on us by CNN. The cassette offered a profusion of

coprophagic mischief, of copulations, of trilingus, of cunnilingus, of

fellatio, but that wasn't enough to attract buyers. The title was there

in order to sell it. The black man had no idea what this eight-letter

word signified. 'It's a really good video,' he told me, 'Look at the

title.'

Sarajevo is becoming a brand name, like Benetton, Coca-Cola and

Nike. (103, my translation of the French translation)

11. Time constraints.

12. Laura Silber and Allan Little's

Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation gives the following account

As the leaders of the procession, gathering in the Parliament forecourt,

declared a 'National Salvation Committee,' the demonstrators swung right,

over the bridge, and into Grbavica. Unwittingly, they were moving up the

hill towards the beseiged police academy and into the Serb guns. Shots

rang out... someone threw a hand-grenade. The crowd panicked and

dispersed. Unknown to most of the demonstrators--for whom the prospect of

open war still seemed preposterous--Sarajevo had suffered its first

casulties of war. Suada Dilberovic, a twenty-one-year-old medical student

from Dubrovnik, was the first to die. She was shot in the chest as she

crossed Vrbanja Bridge and was dead on arrival at Koševo Hospital. (227)

Enida Jahic, a friend and former student, after reading the conference version, added a comment about the memorial now on this site. "The Vrbanja bridge is now [itself] called Suada Deliberovic.... So I guess that the whole bridge stands for her tombstone, and it can hardly be used for propaganda. The inscription is: 'Krv moje krvi potece, i Bosna ne presuši' ('A drop of my blood was spilt, and Bosnia--i.e., the river and the country--has not become dry.')" The inscription was written by the Bosnian poet Abdulah Sidran.

13. My excerpts from the Kaplan text may perhaps be criticized in that they intentionally excise the "big idea" which it is the purpose of this scene to convey (that bourgeois democracy and prosperity, with time, make fascism impossible). He gets "the old Nazi hunter [Simon] Wiesenthal" to mouth this one for him. My point, that Kaplan's distinction between the West and the rest is, to put it as mildly as possible, self-serving, is certainly no less true of his actual thesis. To show that both the distinction and the idea are wrong--which I also believe--would require another essay, and, I'm afraid, another essayist.

14. IFOR stands for "Implementation Force," i.e., the 60,000 troops, led by NATO, that were dispatched into Bosnia-Herzegovina as a part of the Dayton accords. The name has since been changed to "SFOR," an abbreviation of "Stabilization Force."

15. Again, the language here ("All you see," "it") now strikes me as particularly coercive. Moreover, things are no longer as they were then. In the years since this photo was taken, about half of these homes were rebuilt; on the other hand, the home that I show in the next photo hasn't changed much at all.

16. When I sent this essay to my friend in Sarajevo, I added the following comment: "In reading these lines, it occurs to me how the expression is typical of sentimental writing. The person writing this doesn't know this man, and doesn't want to know him. What he wants is a receptacle for his own interpreting sensibility. The man himself, here portrayed as a hero, may conceivably be just the opposite. Or he could just be an ordinary human being. What do we see, if we see?"

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1963.

Boltanski, Luc. La souffrance à distance: Morale humanitaire, médias et politique. Paris: Editions Métailié, 1993.

Calvino, Italo. "Dell'opaco." La Strada di San Giovanni. Milano: Mondadori, 1990. 117-34.

Gjelten, Tom. Sarajevo Daily: A City and Its Newspaper Under Siege. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

Jergovic, Miljenko. Sarajevo Marlboro. Trans. S. Tomaševic. London: Penguin, 1997.

Kaplan, Robert D. Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History. New York: Vintage, 1994.

Kebo, Ozren. Bienvenue au enfer: Sarajevo mode d'emploi. Trans. Mireille Robin. Paris: La Nuée Bleue, 1997.

Musil, Robert. "Monuments." Posthumous Papers of a Living Author. Trans. Peter Wortsman. Hygiene, CO: Eridanos, 1987. 61-64.

Silber, Laura, and Allan Little. Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation. London: Penguin, 1997.

Spelman, Elizabeth V. Fruits of Sorrow: Framing Our Attention to Suffering. Boston: Beacon Press, 1997.