"The World Will Be Tlön": Mapping the Fantastic onto the Virtual

Darren ToftsSwinburne University of Technology

dtofts@groupwise.swin.edu.au

© 2003 Darren Tofts.

All rights reserved.

- The world may be fantastic. The world will be Tlön.

- The cartographers of antiquity have left a profound and fearsome legacy. Only now can we speak of its dread morphology. Spurning the severe abstractions of scale, they achieved exact correspondence: the map occupies the territory, an exact copy in every detail. Here, after centuries of vanity, is exactitude in science, pitiless, coincident, and seamless. I have stood on the threshold of the cave, having escaped the bondage of shadows. I have climbed to the top of the mountain and sought out the tattered ruins of that map. I have discoursed with the scattered dynasty of solitary men who have changed the face of the world. I have come to offer my report on knowledge. I have come to tell you that the world will be Tlön.

- The figure of the map covering the territory has become an indexical figure in discussions of postmodernism. It has come to stand for a problematic diminution of the real in the wake of a proliferating image culture, obsessed with refining the technologies of reproduction, making the copy even better than the real thing. As Hillel Schwartz, author of the remarkable Culture of the Copy, notes, with untimely emphasis, "the copy will transcend the original" (212).

- Preoccupied with the relationship between reality and its copies, postmodernism deflects the idea of an absolute reality in favor of high-fidelity facsimiles. The passage from postmodernism to virtuality involves a shift from copying to simulating the world, from the reproductive practices of photography and film, to post-reproductive or simulation technologies such as telepresence, advanced digital imaging, virtual reality and other immersive environments. This journey from reproduction to simulation involves the disappearance of difference, the breakdown of binary metaphysics and all that we understand by the term representation. The movement from analogue to digital media is a significant event in the diminution of reality's a priori status. It comes on the heels of a long artistic tradition of exploration into the relationship between reality and its representability.

- Fantastic literature is one such mode that has actively explored this nexus of reality and representation, traditionally doing so through the distorting glass of allegory--whether it be in the writings of J.R.R. Tolkien, with his mythical Middle Earth, the dark and insular labyrinth of Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast trilogy, or the miraculous world of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Macondo. In such writing, the creation of imaginary "other" worlds is astonishing, seductive in its realism, in the persuasive weight of presence it delivers. For the time of reading, Mordor's fire and cobwebs are oppressively real, as is the stench and menace of Swelter's kitchen, or the jungle's embrace of a Spanish galleon, festooned with orchids. While fantasy is seen as a discrete form of writing, like science fiction or the gothic novel, it is still an art of fiction, a conjuror's verisimilitude, all smoke and mirrors, sleights of hand, and verbal prestidigitation.

- While the realities of such writing are convincing, they fall short of actually supplanting our own sense of the real. That is, they don't disturb our sense of what is real and what is not. Like all fiction, they are temporary zones, carnivalesque moments in which anything is possible. Without thinking too much about it we know that they are realistic. But we also know they are not real. This intuitive understanding is the safety valve of catharsis, the limit point of identification within the boundaries of a particular cultural technology, whether it is literature or cinema. This certitude, that we are immersed in realistic unrealities, is the metaphysic that allows us to tune into fantasy, live there for a time, and then re-inhabit the real without believing that the fantasy continues beyond the book or the film. It is fantasy's exit strategy. Without this strategy, this metaphysical way out, we run the risk of psychosis, certainly as Sigmund Freud had imagined it, as a sustained and problematic over-identification with a fictional character or world. Please allow me to introduce myself: I am Titus Groan, and my quest in life lies somewhere beyond the agonizing rituals of Gormenghast. I must flee its stone lanes and unforgiving walls. Can anyone here help me?

- Cultural theorists, such as Umberto Eco and Jean Luis Baudrillard, have given other names to such extreme identifications with fictions, names that defined the cultural climate of the last decades of the twentieth century--terms such as simulacrum, hyperreality, the desert of the real, faith in fakes, the culture of the copy. Not wanting to be seen to lag behind the po-mo cognoscenti of Europe, Hollywood has manufactured a genre of cyber-technology films that equally responds to this perception of the closure of fantasy's exit strategy, in which there is no longer a way out, a return to the real. Films such as The Truman Show, The Matrix, and Dark City, to name but a few, postulate worlds of hard-wired false consciousness, in which what is taken for reality is, respectively, the most insidious reality TV, the ultimate simulation, the perfect virtual reality. To be outside the deception is not to be mad, as Michel Foucault would perhaps have it, but rather to be all-powerful, in control of reality and its representations, the architect of representation as reality--the auteur, in other words, as demiurge.

- This brings us to the qualitative and disquieting difference between the fantastic and the virtual. In the realm of the fantastic, we don't need anyone to welcome us to the real world, since we reliably know what it is and what it is not. When the exit strategy of fantasy is closed, or denied, we have no way of knowing that we don't even know there is a difference anymore between fantasy and reality. Unless we are liberated from the simulacrum, like Neo in The Matrix, or find the out-door to a reality we never knew existed, like Truman, it's business as usual in the real world, where people go to work, go to the football on the weekends and catch the occasional paper at cultural events, such as the Biennale of Sydney. Welcome to the desert of the real.

- In the desert of the real you can still find, if you are lucky, ruptures in the seam of things, little tears in the otherwise flawless surface of the map that covers the territory. One of these is in fact a parable about maps and territories, simulation and fabricated reality--a parable about the creation of the world. This artifact is a short fictional text written by the Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges. First published in 1940, "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" occupies an important place in the history of twentieth-century speculation on the relationship between fantasy and reality. It is at once a meditation on and an example of this relationship. Indeed, for Borges, terms such as fantasy and reality are in no way absolutes, nor are they dependent figures within a binary opposition. They are rather manifestations of possible worlds, projections of the world as it may be.

- We have much to learn from "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius." Although he died in 1986, Borges is still very much our contemporary. His presence, more than we can perhaps ever realize, or imagine, is everywhere felt but nowhere seen at the start of the third millennium, this year, this day, this afternoon. As we invest more time, money, and metaphysical capital in the cultural technologies of virtuality, we are perhaps closing off our own exit strategies, dissolving the liminal zones of genre and metaphysics that partition the fantastic and the real. We can learn something of how we are doing this, as well as the consequences of doing it, from "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius." It is worthwhile, therefore, briefly to review the fiction in this context, to refresh the memory of those who are familiar with it, to submit it to the memory of those who are not. For those of you from the border, who have difficulty with me describing Tlön as if it is a fiction--and not an assured commentary on your world--I humbly beg your indulgence.

- As with many of Borges's stories, "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius"

begins with a found object. It is a single volume, number 46 to be

precise, of a pirated edition of the Anglo-American

Cyclopaedia, published in New York in 1917. The volume is

unremarkable in every way, apart from four extra pages that are contained

in this singular volume only and not in any other copy of this particular

edition. The superfluous pages contain a detailed account of a

previously unknown and uncharted region of Asia Minor called Uqbar. The

narrator and his companion, Adolpho Bioy Cesares, search in vain for

further references to Uqbar, but nothing in the way of corroborating

evidence emerges from their labors, even from hours spent at the National

Library of Argentina. The entry on Uqbar contains detailed information

on the history, customs, geography, and literature of this mysterious

region. One piece of information will suffice to impart a flavor of the

piece:

The section on Language and Literature was brief. Only one trait is worthy of recollection: it noted that the literature of Uqbar was one of fantasy and that its epics and legends never referred to reality, but to the two imaginary regions of Mlejnas and Tlön. (29)

- After further research, "events," the narrator observes, "became

more intense" (40). It is discovered that the documentation of Uqbar was

in fact the aborted precursor of a more ambitious project, undertaken by

what is subsequently revealed as a secret society, originating in the

seventeenth century--a kind of enlightenment Sokal hoax on a

trans-historical scale. More ambitious and sublime in its conception and

scope, this society, which included George Berkeley as one of its number,

set out to invent the fictitious history of an entire planet, called

Tlön. The imprimatur of this society, Orbis Tertius,

is found in a similarly unlikely volume--of which there exists, again,

only one copy--entitled A First Encylopaedia of Tlön.

In this one volume we encounter the eclectic miscellany of detail, the reassuring kind of data and information that adheres reality to representation, the documentary

veracity that endows the encyclopedia with the solidity of truth,

authenticity, and knowledge:

Now I held in my hands a vast methodical fragment of an unknown planet's entire history, with its architecture and its playing cards, with the dread of its mythologies and the murmur of its languages, with its emperors and its seas, with its minerals and its birds and its fish, with its algebra and its fire, with its theological and metaphysical controversy. And all of it articulated, coherent, with no visible doctrinal intent or tone of parody. (31)

- As James Woodall, Borges's most recent biographer, has noted, "The discovery of another. . . planet in science fiction is generally a cue for extravagant fantasy; for Borges in this story it was a way of reviewing the world, of offering a critique of reality" (115). In this respect history is everything. Just as Mervyn Peake had used his fiction to explore his time spent at Belsen as a war-time illustrator, so Borges attempted to come to terms with the chaotic horrors of war and the spurious symmetries of the day--dialectical materialism, anti-Semitism, Nazism--in the creation of a harmonious world. But in coming to terms with it he did not attempt to understand it, but rather to replace it altogether. For a world at war, the desire to submit to Tlön, to yield to the "minute and vast evidence of an orderly planet," was overwhelming (42). But such is the stuff of allegory, the tidy protocols of hermeneutic neatness. What better way to explain the embrace of a fictitious reality that is superior in every way to the wreckage of contemporary history?

- But this is not all there is to the story. Borges in fact turns the allegorical mode of fantasy in on itself, closing off its exit strategy and interpolating us, the readers outside-text, along the way. There are a number of things in this fiction that can't be simply written off as allegorical parallel (that is, the interpretation of Tlön as metaphor, as the projection of an ideal world). The world of Tlön, we quickly realize, is palpable and capable of affecting dramatic outcomes in the real world. The First Encylopaedia of Tlön first makes its appearance in 1937, received, as certified mail, by a mysterious person called Herbert Ashe. Little is known about Ashe, other than the inscrutable, yet forthright detail that in his lifetime "he suffered from un-reality" (30). What is beyond doubt is that Ashe was one of the collaborators of Orbis Tertius, and three days after he received the book of Tlön, the book he helped bring into this world, he died of a ruptured aneurysm. We know, too, that as part of their process of rhetorical corroboration, the society of Orbis Tertius disseminates objects throughout the world that cohere with information to be found in the First Encylopedia of Tlön. Such objects, like the forty volumes of the First Encyclopedia of Tlön, are attenuations, material reinforcements, simulacra that solidify the fictitious detail of the books in memory. We could call these objects "proof artifacts," like the scattered ephemera of a holiday never actually taken in Philip K. Dick's 1962 story, "We Can Remember It For You Wholesale" (the text which became the basis of the film Total Recall), or the family photographs coveted by the replicant Leon in the film Blade Runner.

- But there is a difference, of a metaphysical kind, between a suggestive corroboration, a simulated mnemonic device, and something that can't be accounted for in material terms, such as the small, oppressively heavy cone that is found on the body of a dead man in 1942. Representing the divinity in certain regions of Tlön, it is, according to the narrator, "made from a metal which is not of this world," and is so heavy that a "man was scarcely able to raise it from the ground" (41). No one knew anything of the man in whose possession the cone was found, other than the fact that he "came from the border" (41). Here is an instance of the imaginary made flesh, the uncomfortable collision of worlds that we expect to forever remain discrete. It is a kind of perverse, Eucharistic event, the transubstantiation of the fictional into the material, the crossing over from one border to another, from one ontological realm into another--the "intrusion of this fantastic world into the world of reality" (41). Holding this enigmatic object in his hand, the narrator reflects on "the disagreeable impression of repugnance and fear" it instills in him (41). Here is the nausea of the simulacrum, the supplanting of reality by fantasy. Rachael Rosen encounters this dread in Blade Runner when Deckard exposes her childhood memories as belonging to someone else. The contemporary technological shift from one media regime to another, from reproductive to simulation or virtual technologies, entails a similar ontological blurring of worlds that may not be so easily resolved through allegory.

- How do we comprehend, for example, the ability of Neo in The Matrix to "know Kung Fu" without ever having been taught it, without learning its philosophies and techniques as a discipline? The fact is there is little "ability" to his knowing Kung Fu, because he has not acquired it, but rather he has been programmed to know it (together with its cultural resonances and quotations, from Chuck Norris roundhouse kicks to Bruce Lee's trademark cockiness). His experience of Kung Fu is a simulated rather than an actual thing, akin to the competence that airline or military pilots derive from spending hours in flight simulators. The ability to know how to do Kung Fu, repeatedly and without thinking about it, is an issue of second nature, of acquired habit that has become intuitive. The difference here is that second nature, in Neo's case, is not preceded by first-hand experience.

- Such is the consequence of the shift from one media regime to another. In a fine essay that discusses virtuality in relation to Ray Bradbury's 1952 short story "The Veldt," Ken Wark argues that the futuristic, holographic nursery in that text is a technology of the "too real." This virtual technology--which is a cross between a children's playroom and the Holodeck from Star Trek--exceeds the real by manifesting simulacra, such as lions, into the real world. Such manifestations are akin to psychiatric irruptions of the unconscious in waking life. They are affects capable of real and, as it turns out, destructive consequences. This is no allegorical wunderkammer, since the logic of representation has ceased to exist within its machinations.

- If Bradbury's holographic nursery has anticipated anything achieved so far in the name of new media, it is not so much the immersive, virtual-reality environment as the new, "total realism" of hybrid cinema (that is, the convergence of film and digital effects). Lev Manovich, in The Language of New Media, describes how the use of digital technologies in the pursuit of greater realism in cinema has created effects that are "too real" (199). That is, the ability to simulate three-dimensional visual realities--such as the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park--has created a perfect visuality that, paradoxically, has to be "diluted to match the imperfection of film's graininess" (202). For Manovich, digital simulation has precipitated a new order of experience, a synthetic reality that exceeds the limitations of film's attempts to represent real-world experience.

- As evidence of the persuasiveness of synthetic reality, I submit

the following image:

This image, created by artist Troy Innocent, represents the kind of fusion of real people with computer-simulated objects that Manovich describes in relation to the formation of synthetic realities. Created at my request, this image beautifully illustrates the point that synthetic realities can blur the distinction between formerly discrete worlds. Bill Mitchell, author of The Reconfigured Eye. Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era, would probably refer to this image as a "fake photograph," an example of the new aesthetic possibilities of digital imaging. I prefer to think of it as a snapshot from Tlön, the infiltration of one world by another. Mitchell is sensitive to the metaphysical implications of digital imaging, noting that "as we enter the post-photographic era, we must face once again the ineradicable fragility of our ontological distinctions between the imaginary and the real" (225).

Figure 1 - It is such forecasts of the consequences of our embrace of the virtual that confirm the continued importance of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" in today's world. As a "critique of reality," it not only documents an account in the 1940s of the changing of the face of the world, but also anticipates the technological reinvention of the real. Such reinvention, in the name of virtual and simulation technologies, prompts the question: do we need a reality any more, when multiple realities can be created synthetically? As a synthetic reality, "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" draws us, the readers of Borges the writer, the people outside-text, into its perplexing ontological orbits. That is, our experience of the world is affected by our involvement in the story. Like the inhabitants of Tlön, we find ourselves engaging with metaphysics as if it were a "branch of fantastic literature" (34). Borges defiantly teases the readers' desire to believe in the reality of the discovered world, secure, as they are, in their assured, known world outside-text. He tests, in other words, the extent to which readers are prepared to forestall their exit strategy, to explore the outer limits of credulity to do with this previously unknown world. After all, all the reference points in the story are verifiably factual, such as the Brazilian hotel, Las Delicias, in which Herbert Ashe is sent the mysterious First Encylopaedia of Tlön, or the narrator's companion, Adolfo Bioy Cesares, the person who brings the troubling issue of Uqbar to his attention, in reality one of Borges's closest friends and literary collaborators. Borges's style is clearly documentary-like in approach: prudent, well researched, and sound, with very few literary flourishes or overt metafictional moments. Indeed, it is more accurate to call "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" an essay rather than a fiction, reading, as it does, with the impersonal, measured factuality of the encyclopedia entry. In the hands of an essayist documenting the conceit of Tlön, Borges's methods of persuasion--or are they in fact forms of evidence?--are compelling. In reflecting on one of the theories of time subscribed to by the inhabitants of Tlön, for example, he notes that "it reasons that the present is indefinite, that the future has no reality other than as a present hope, that the past has no reality other than as a present memory" (34). Furthermore, he notes, in a footnote, that this question had detained the attention of the great Bertrand Russell, who supposed "that the planet has been created a few minutes ago, furnished with a humanity that 'remembers' an illusory past" (34). He identifies the reference as The Analysis of Mind, 1921, page 159. You can pursue the citation if you like, but take it from me, it is not bogus.

- This is one of the many troubling moments in which information

from outside-text corroborates the collaborative, invented world of

Borges's fiction. That is, facets of this grand guignol can be chased

down as referential points in our own world. We can confirm these

references from scholarly sources, such as The Analysis of

Mind, or volume 13 of the writings of Thomas De Quincey. As with the people within the diegetic world of the story,

it is difficult to rationalize the feeling that our reality, or at least my reality, is not

yielding to Tlön. In considering the parallels between "Tlön, Uqbar,

Orbis Tertius" and The Matrix, I

was startled when I re-read the story and came upon one of the

doctrines of Tlön: that "while we sleep here, we are awake elsewhere and that

in this way every man is two men" (35). The duality of actual self and

digital representation in The Matrix is the anchor that

smoothes out and reconciles the split between the worlds of meat and

of virtuality--the conduit between different ontologies, different

metaphysical states. So, in playing around with this parallel, looking

for an angle, an opening gambit, you can imagine my concern, when reading

of the progressive reformation of earthly learning in the name of

Tlön, at discovering that "biology and mathematics also await their avatars"

(43).

Figure 2: A Surreal Visitor - Events became more intense as I moved deeper into the vertigo of writing about Tlön. On reading the Melbourne The Age Saturday Extra on the 20th of April 2002, it was with a mixture of fascination and alarm that I came across an account of a little-known visit to Melbourne by Borges in the late Autumn of 1938. Written by Guy Rundle, under the title of "A Surreal Visitor," the piece took me quite by surprise. My first inclination was to check the date: it wasn't the 1st of April. To my knowledge Borges had never traveled to Australia, a view quickly confirmed in the pages of the biographies at my disposal. Yet the detail was all here: he arrived on May 16th at the invitation of John Willie, a member of Norman Lindsay's bohemian circle and admirer of Borges's work, gave a lecture at the Royal Society entitled "The Author's Fictions," and spent much of his time in the domed reading room of the State Library of Victoria. These were all likely, Borgesian places, places that I would expect the great man of letters to frequent if he was in Melbourne, right down to the oneiric epiphany of a set of locks in a Glenhuntly shop window. In all, Borges spent ten days in Melbourne before returning to Buenos Aires, the smell of eucalyptus no doubt still lingering in his mind (a sensation that would seem to have found its way into the remarkable opening line of his story "Death and the Compass," published in 1944).

- On closer inspection, it became clear that Rundle was playing a very erudite joke on his readers, treating Borges by the rules of his own game, so to speak. Indeed, the first line read like a Borges pastiche, citing an author, a prodigious event and an ironic allusion, all within the strict economy of a single sentence: "Devotees of the writings of Jorge Luis Borges will not be surprised by the recent discovery that the great Argentinean writer once spent some time in Melbourne." The rhythm and balance of the syntax recalls the opening sentence from "Death and the Compass": "Of the many problems which exercised the reckless discernment of Lönnrot, none was so strange--so rigorously strange, shall we say--as the periodic series of bloody events which culminated at the villa of Triste-le-Roy, amid the ceaseless aroma of the eucalypti" (106). The suggestion that Borges's admirers "will not be surprised" is the ironic allusion, a rhetorical maneuver gesturing to the fact that a devotee of Borges, well versed in the art of fabulation, would recognize that Borges is the perfect subject for such a fiction.

- Rundle's piece cannily imitates distinctive features of Borges's writing and, in particular, "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius"--a text famous for its challenge to readers to accept, or at least consider, the reality of a fictitious world. For all we know, Rundle may have written his story with "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" at his elbow, open at page twenty-eight. On that page you will find one of Borges's own ironic, reflexive allusions, as the narrator and Bioy Cesares discuss the article on Uqbar in the Anglo-American Cyclopaedia. The key detail here is that they found the piece "very plausible" (28). Rundle's piece is crowded with plausible detail that is very specific and combines known facts about Borges's life--such as his involvement with Victoria Ocampo and the important literary magazine, Sur--with previously unknown information. It sounds plausible that someone in Norman Lindsay's bohemian circle would have been aware of Sur and passionate enough to mentor the Argentinean writer's visit to Australia. Most of all, Rundle exploits Borges's delight--especially indulged in "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius"--in inviting the reader to trust in evidence that is confined to fugitive or lost documents, missing or unverifiable detail. The record of Borges's visit, for instance, is "confined to a few notes made for a poem (never written) that Borges made in a notebook, which recently came to light at a house in Cordoba, and some letters written to fellow novelist Bioy Cesares" (5). The reference to Bioy Cesares is a delightful touch, an unquestionable source offsetting the potential unreliability of such fragmentary, incomplete records. Borges's lecture, presented to the Royal Society is, not surprisingly, "also lost, if ever written down" (5). Nor should we be surprised to detect the occasional flash of audacity as Rundle warms to his work, noting that a vernacular reference to a "strange lecture by a Spanish chap" is attributed to Harold Stewart, who, along with James McAuley and writing under the pseudonym of Ern Malley, perpetrated one of the great literary hoaxes of the twentieth century.

- I have reflected that it is permissible to see in this story of a visit never taken a kind of palimpsest, through which the traces of Borges's "previous" writing are translucently visible. It is especially noteworthy that Rundle exploits the plausible conveyance of tenuous information, or what Borges, in "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," refers to as a tension between "rigorous prose" and "fundamental vagueness" (28). This is noteworthy. Of the Borges stories Rundle refers to in the piece--and they are some of his most well known--no mention is made of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," arguably his most famous work. This absence is also a tour de force of citation by omission, implicit in the gesture to a line from "The Garden of Forking Paths," in which the word "chess" is the answer to the following question: "In a riddle whose answer is chess, what is the only prohibited word?" (53).

- One can imagine that such a persuasive piece of writing would be

not only plausible, retrospectively writing Jorge Luis Borges into

Melbourne's literary memory, but revelatory to many readers. Once again

a line from "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" came to mind: "a fictitious

past occupies in our memories the place of another, a past of which we

know nothing with certainty--not even that it is false" (42-3). A trip

to the Exhibition Gardens or the reading room at the State Library would

never be the same again, knowing that the great Borges had left his trace

there. But literary hoaxes don't fool everyone. Nor are they to

everyone's taste.

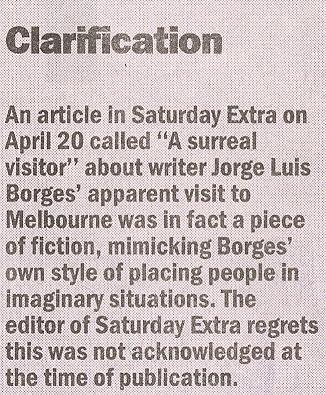

Figure 3: Disclaimer - On the following weekend, I can't say that I was surprised to read

the following disclaimer:

An article in Saturday Extra on April 20 called "A surreal visitor" about writer Jorge Luis Borges's apparent visit to Melbourne was in fact a piece of fiction, mimicking Borges's own style of placing people in imaginary situations. The editor of Saturday Extra regrets this was not acknowledged at the time of publication. (2)

- Now this is a real Borgesian test of credulity. I find the idea of Jason Steger, the literary editor of the Saturday Extra, forgetting to mention this fact far less plausible than the idea of Tlön itself. Jason Steger is clearly the Herbert Ashe of this conspiracy. This disclaimer, while predictable, was actually quite dissatisfying and ruined what, for me, was a marvellous piece of invention. I could see it now, many years down the track, my students wondering, with restrained awe, if they had sat where Borges had in the domed reading room of the State library. So out of some peculiar nostalgia for the lost memory of a visit that never was, I decided, in the spirit of Rundle's piece, to look into the some of the "facts" he assembled, to re-trace and re-claim some of the steps of this sublime, phantom visitation. I didn't expect to find any corroboration, but I wanted to at least participate in the fiction, to walk in the ubiquitous shadow of this rigorous Latin American genius. Now this is where this story gets really weird.

- On the 23rd of April I went to do some research at the State

Library of Victoria. Had the domed reading room been open (it was then

still under renovation), I would have sought out that imaginary vibe.

Mindful of the lessons of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," I suppose I

wanted to imaginatively place Borges in the scene, to fill the gaps that

I knew, full well, I would find. A strange inclination, I know, but then

we are dealing with a writer who, more than any other, has encouraged us

to question what we accept as real, as verifiable, as truth. I wanted to

find the spaces of his absent presence. After all, Borges was a

deconstructionist avant la lettre and he would have known only

too well that if there are no traces, there is no presence.

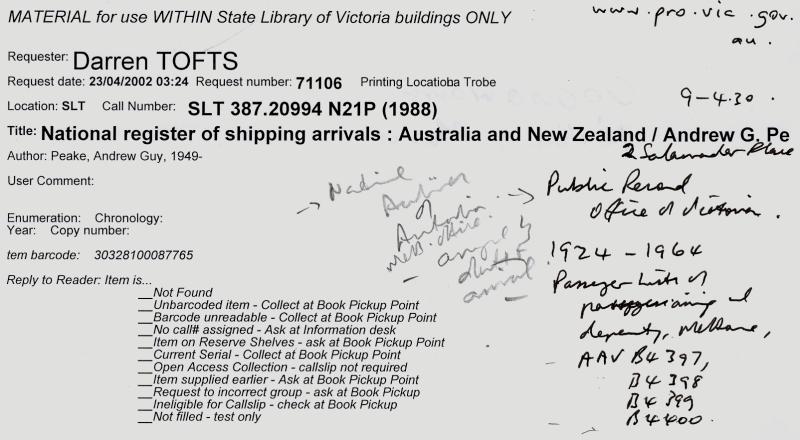

Figure 4: National Register of Shipping Arrivals - My first reference, the National Register of Shipping Arrivals: Australia and New Zealand, was promising,

but by no means conclusive. The volume was in fact an index of passenger lists between the years 1924 and 1964, held

elsewhere, at the Melbourne Office of the National Archives of Australia to be precise, which is part of the Public Record

Office of Victoria. While a deferral, it was at least a start. That reference would have to wait for another day.

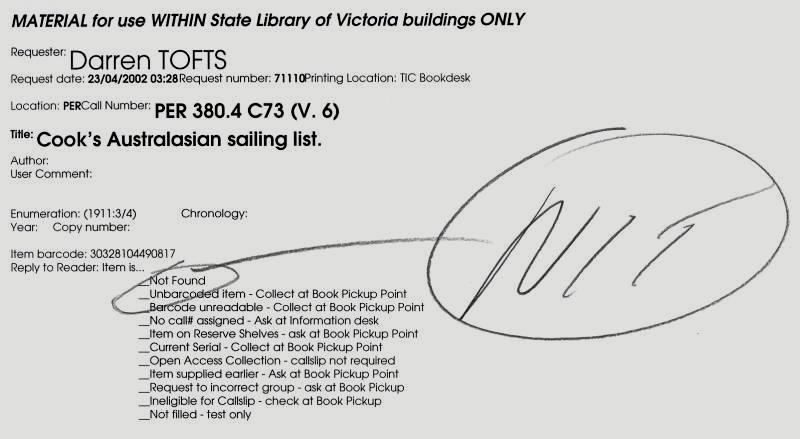

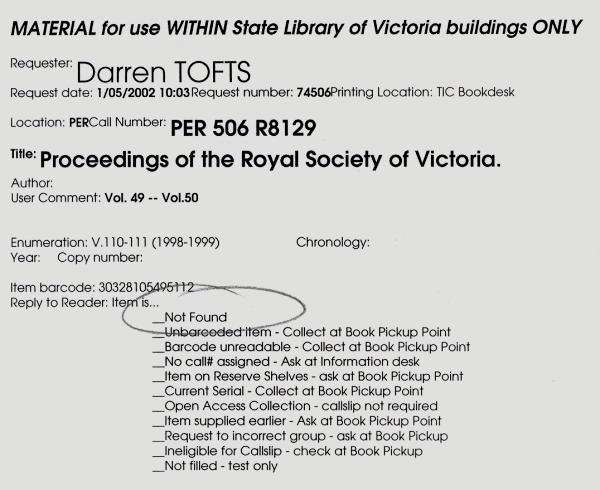

Cook's Australasian Sailing List was my next port of call. When requesting the book, I received every

indication that

it was available, and

as the stacks are not open to public access, it was highly likely that I would get a return.

Figure 5: Cook's Australasian Sailing List - I was disappointed, then, to receive my request slip and no book. The slip indicated that the volume could not be found. The librarian on duty acknowledged that this was indeed unusual, but I was prepared to accept it as part of the hit-or-miss process of library research.

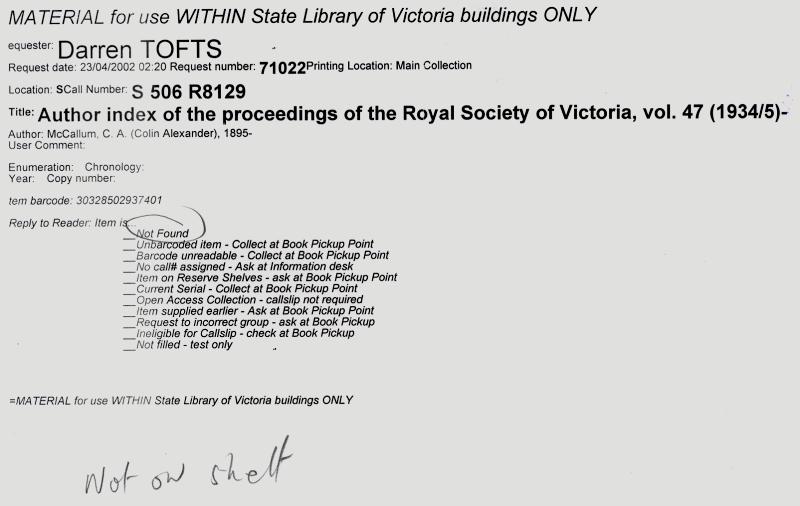

- I started to get concerned, though, when my next request also bounced

on me. Consistent with Rundle's imaginary itinerary, I wanted to consult

the Author Index of the Proceedings of the Royal Society of

Victoria to find no evidence of Borges's guest lecture there.

Figure 6: Author Index of

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria - Not only did I receive a note saying that the volume was not found, but on the request slip there was also a handwritten note indicating that the volume was "Not on shelf." I left the library with nothing to show for my efforts. While, as I had expected, I did not find any positive evidence of Borges's visit to Melbourne, I did not find, either, any negative evidence to prove that he did not visit.

- I returned to the library the following day. On the way there, I

stopped off at the Royal Society. The person with whom I spoke, while

decidedly brusque and unhelpful, did confirm that a guest speaker would

indeed have been registered in their Proceedings.

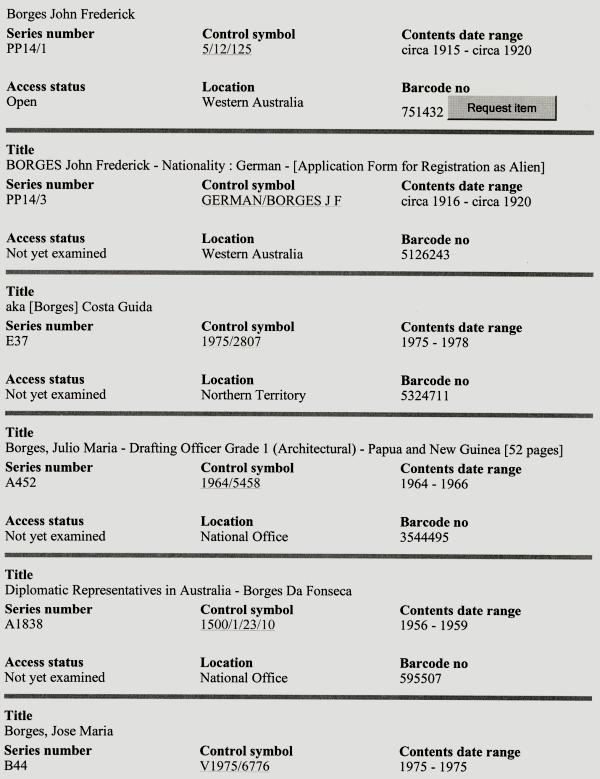

Figure 7: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria - This time at the library, the exact volume of the Proceedings,

containing everything from 1938, was not found. A trip around the block

to the Public Records Office was more promising. A database search of

passenger ships yielded no records whatsoever of the Koumoundouros, nor

did a search of passengers coming into Melbourne as "legal aliens" in

1938 include a Jorge Luis Borges, though, as you will see from this

sample of the inventory, the name Borges was not an uncommon one for

arrivals in Melbourne that year:

Figure 8

Click on image for larger view - But what was starting to disconcert me, in an odd, metaphysical kind of way, was that this confirmed evidence sat cheek by jowl with inconclusive, irresolute results. Nothing, it seemed, could be proved false. The whole thing was actually starting to resemble "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius"--real life as an uncanny form of allusion or repetition. It was as if the very task of researching Borges's imaginary visit to Melbourne had unleashed a kind of strange code or virus, a meme, a Borges meme that had the potential to change the way we perceive reality. But unlike the genetic or ideological connotations of this notion that we find in Richard Dawkins and Douglas Rushkoff, the Borges meme was of a metaphysical nature, short-circuiting all attempts to confirm its unreality, even in the face of other plausible evidence that declared that the whole affair was a fabulation (not the least of these being Jason Steger's disclaimer printed in The Age). Indeed, for a fleeting instant, the idea did cross my mind that along with Steger, Rundle belonged to the same secret society of intellectuals, Orbis Tertius, who made the world Tlön. Their quest, it could be argued, was an attempt to animate what Rundle called, referring to Melbourne, an "unremarkable and overfamiliar city" (5). This could be achieved through projecting the city anew through the exotic eyes of a "mysterious visitor" (5). The tantalizing possibility that this imaginary event might be real, or the more interesting dynamic of its ambivalent veracity, is the occasion for a kind of belief, a virtual, simulated belief in the reality of the unreal. To paraphrase a line from Borges's "The Library of Babel," it suffices that his visit to Melbourne be possible for it to exist.

- To conclude, the idea of a Borges meme gets us to the

disconcerting heart of this writer's metaphysics. Unlike fantasy in its

allegorical mode, Borges's metaphysical fictions intrude into what we

understand to be real, the obvious world outside-text. Borges writes of

the undecidable, the interzone between fiction and non-fiction,

documentary writing, and fabulation. It is an unclassifiable space of

paradox and contradiction, the sensation, vague yet familiar, that what

seems unlikely may be a forgotten reality--a confused sensation akin to

the afterglow of a vivid dream, before it vanishes in wakefulness. As we

have seen, this is a paradox that we have been confronting for some time

in the name of postmodernism and more recently in relation to virtual

technologies. In the age of virtuality, we are once again retracing

Borges's footsteps as he guides us, a latter-day Ariadne, through the

labyrinthine fantasy that we call the real.

Postscript

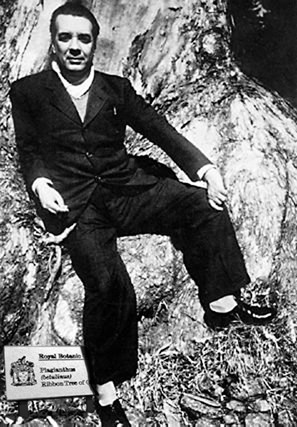

- In the days leading up to my departure for Sydney, I received a

parcel from the Royal Society. Unaccompanied by a letter or note of

explanation--they were as perfunctory as ever--I found this photograph.

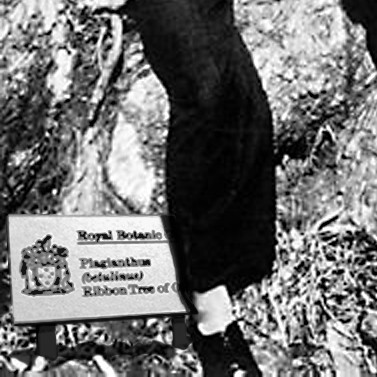

Figure 9 - It is without doubt a photograph of Borges, probably in his late thirties. This would date it around 1938 or 1939. The

intriguing detail is the plaque at his feet. On closer inspection--thanks to my friend Chris

Henschke--it reveals the State of Victoria coat of arms. The botanical

name of the tree on which he is reclining, the Ribbon Tree of Otago,

grown in Melbourne since the nineteenth century, can be verified in

Guilfoyle's Catalogue of Plants Under Cultivation in the Melbourne

Botanic Gardens, published in 1883.

Figure 10 - The only other thing of note about the photograph is that its

verso bears an inscription in an elegant copperplate. For some reason

this would not scan properly, but I offer the following transcription:

I remember him, with his face taciturn and Indian-like and singularly remote, behind the cigarette.

Department of Media and Communications

Swinburne University of Technology

dtofts@groupwise.swin.edu.au

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2003 Darren Tofts. READERS MAY USE

PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S.

COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED

INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Works Cited

Borges, Jorge Luis. "Garden of the Forking Paths." Labyrinths 44-54.

---. "Death and the Compass." Labyrinths 106-17.

---. Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings. Eds. Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1970 [1964].

---. "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius." Labyrinths 27-43.

"Clarification." The Age Saturday Extra. May 4, 2002.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT P, 2001.

Mitchell, William J. The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era. Cambridge, MA: MIT P, 1992.

Rundle, Guy. "A Surreal Visitor." The Age Saturday Extra. April 20, 2002.

Schwartz, Hillel. The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles. New York: Zone, 1996.

Wark, McKenzie. "Too Real." Prefiguring Cyberculture: An Intellectual History. Eds. Darren Tofts, Annemarie Jonson, and Alessio Cavallaro. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT P, 2003.

Woodall, James. Borges: A Life. New York: Basic, 1996.