"Eden or Ebb of the Sea": Susan Howe's Word Squares and Postlinear Poetics

Brian ReedUniversity of Washington, Seattle

bmreed@u.washington.edu

© 2004 Brian Reed.

All rights reserved.

- In Poetry On & Off the Page (1998), Marjorie Perloff argues that the era of free verse may be drawing to a close. She examines recent work by a number of avant-garde poets--among them Caroline Bergvall, Karen Mac Cormack, Susan Howe, Maggie O'Sullivan, Joan Retallack, and Rosmarie Waldrop--and concludes that, whereas classic free verse depends on lineation to distinguish itself from prose, today's "postlinear" poetry considers "the line" to be "a boundary, a confining border, a form of packaging" (157). This new species of verse freely violates longstanding literary conventions governing such aspects of page design as white space, punctuation, capitalization, font type, font size, margins, word spacing, and word placement. These experiments typically result in unusual "visual constructs" that impede, deflect, and otherwise coax readers' eyes out of their habitual, left-to-right, top-to-bottom progress through a text (160). The predictable "flow" of the old free verse line thereby gives way to a "multi-dimensional" field of unexpected movements, arrests, connections, and disjunctions (160-63).

- Perloff hesitates over how to define this emergent poetic sensibility. "I have no name for this new form," she confesses. The "new exploratory poetry [...] does not want to be labelized or categorized" (166). The individual works that Perloff examines vary so greatly in page layout--some resembling shaped prose, some Futurist words-in-freedom, some advertising copy--that it would be hard indeed to find shared identifying traits such as the left-justified and right-ragged margins that typify most twentieth-century free verse.

- This formal diversity signals more than the breakdown of the old paradigm for verse-writing. Postlinear poets have begun inquiring into what W.J.T. Mitchell calls the "image-text," that is, the "whole ensemble of relations" between the visual and verbal (89). Moreover, as Mitchell alerts us, the "study of image-text relations" is far from a straightforward endeavor. Rarely do "image" and "text" work together in perfectly coordinated fashion. On the contrary, "difference is just as important as similarity, antagonism as crucial as collaboration, dissonance and division of labor as interesting as harmony and blending of function" (89-90). Postlinear poets revel in this ambiguity. They have recast their writing as a "composite art" that hybridizes "sensory and cognitive modes" while also "deconstructing the possibility of a pure image or pure text" (95).

- If some poets have thereby discovered liberating possibilities for self-expression, literary critics, in contrast, have been presented with a new challenge. Postlinear poetry presents in miniature a dilemma that Mitchell considers inherent to the problem of "the image-text." He argues that there is no "metalanguage" available or possible that could enable critics to speak confidently, synoptically, and transhistorically about the interface between the verbal and the visual (83). Almost every artistic exploration of that interzone proceeds differently toward noncoincident ends. In response, critics have had to insist on "literalness and materiality" in their analyses instead of resorting to too-abstract or falsely generalizing statements (90). They have had to "approach language as a medium rather than a system, a heterogeneous field of discursive modes requiring pragmatic, dialectical description rather than a univocally coded scheme open to scientific description" (97).

- Developing a satisfactory account of postlinear poetics will almost certainly require a series of disparate but complementary forays into the concrete writerly practices of particular, relevant authors. As Mitchell warns us, induction and deduction would misconstrue the phenomenon, insofar as they seek to replace the messiness of individual cases with the cleanliness of "scientific description." Only by amassing enough specifics, in all their idiosyncrasy and waywardness, will we gain a sufficiently detailed, trustworthy mapping of contemporary poetic involvement in "the image-text."

- This scholarly task is complicated by the fact that many poets embarked on their postlinear experiments within the context of ambitious pre-existing projects. Most of the poets that Perloff identifies as postlinear have careers that stretch over decades, and several are also known for their work in other media and genres (Bergvall as a performance artist, O'Sullivan as a visual artist, Waldrop as a novelist). In each case, we may discover that there is a prodigious amount of prehistory and background to establish before one can speak meaningfully about a poet's visual sensibility.

- This article seeks to demonstrate both the rewards and drawbacks of the quest for an adequate understanding of the emergent postlinear poetries. It concentrates on explaining the origins, functions, and value of a single visual device--the "word square"--in Susan Howe's poetry. Though this might seem a narrowly focused topic, it quickly ramifies. One has to examine not only Howe's verse but also her early work as an installation artist, her debts to the painters Ad Reinhardt and Agnes Martin, her apprenticeship to the Scottish writer Ian Hamilton Finlay, her qualified faith in the divine, and her recurrent fascination with the ocean. Howe's visual experiments only attain their fullest significance when read against the backdrop of her career in its entirety. Perloff has warned that the end of free verse means we can no longer rely on the tried-and-true vocabulary of line breaks, stanzas, and enjambment to orient ourselves when analyzing verse; we will have to master "other principles" that await names, let alone workable definitions (Poetry On & Off the Page 166). The quest to understand Susan Howe's word squares reveals just how arduous the road to such mastery will be.

- Susan Howe first came to prominence as a writer affiliated with Language Poetry, an avant-garde literary movement that originated in New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Washington, D.C., in the 1970s.[1] In the 1980s, her literary-critical study My Emily Dickinson and her long poems Defenestration of Prague, Pythagorean Silence, The Liberties, and Articulation of Sound Forms in Time attracted such academic partisans as Jerome McGann, Linda Reinfeld, and Marjorie Perloff. In the 1990s, further publications such as The Nonconformist's Memorial, Pierce-Arrow, and The Birth-mark solidified her fame as one of the most original, erudite, and challenging of postmodern U.S. poets. The secondary literature on her writing is growing quickly--a search of the MLA Bibliography turns up more than forty articles--and the first monograph on Howe, Rachel Tzvia Back's Led by Language, appeared in 2002.

- Since the 1970s, Howe has been known for her bold experiments with the look of her poetry.[2] Unlike such other postlinear poets as Bob Cobbing and Steve McCaffery, however, Howe has not invented new forms with almost every new volume. Instead, she has tended to repeat, with variations and refinements, a small set of characteristic layouts. Hannelore Möckel-Rieke has identified four principle page designs: (1) "more or less compromised regions of text" with assorted indentations and outtakes; (2) a form resembling that of ballads, often consisting of two-line stanzas; (3) a radicalized, "exploded" style with obliquely positioned, intersecting fragments of text; and (4) sections consisting of words, partial words, nonce words, numbers, punctuation marks and/or letters arranged into more-or-less rectangular shapes (291).

- Of these four kinds of layout, the fourth one has proved the most baffling. The other three are either conventional enough to escape comment (as with the second) or reassuringly similar to modernist precursors.[3] Howe's "more or less compromised regions of text," for instance, recall such Joycean episodes as the Aeolus chapter in Ulysses and the night lessons chapter in Finnegans Wake. These passages generally emphasize the author's role as a redactor and manipulator of material originally written by others.[4] And the "exploded" pages occur at the points of maximum violence in Howe's work, such as the execution of King Charles I in A Bibliography of the King's Book or, Eikon Basilike (EB 56-57).[5] These episodes hark back to F.T. Marinetti's wild typographical intimations of the clash and noise of modern warfare.

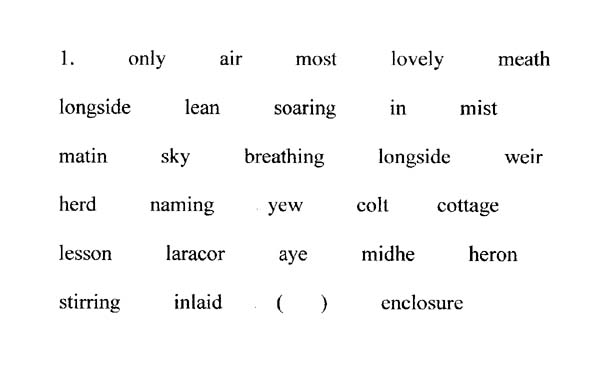

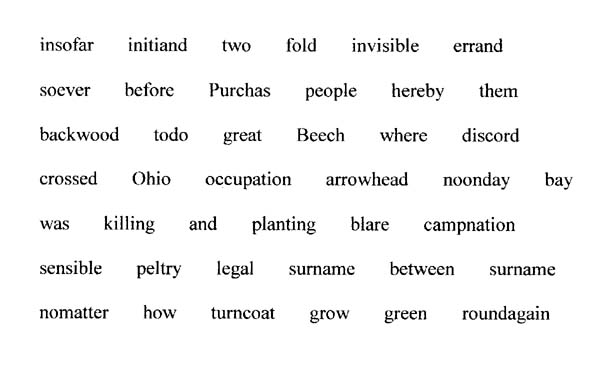

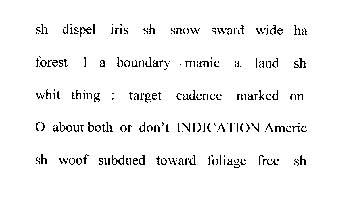

- In contrast, Howe's ragged arrays of words, part words, and symbols--which, following Rachel Blau DuPlessis, I will be calling "word squares" (138)--have few or no obvious literary precedents.[6] One cannot rely on intertextuality or allusion to explain their meaning. Yet they recur mysteriously from poem to poem (see, for example, Figures 1-3).[7] Moreover, they always appear at charged junctures, when the writing confronts the limits of cognition and representation. Examining a particularly striking instance in its original context will demonstrate the enigmatic centrality of this technique in Howe's work.

Howe's celebrated long poem Articulation of Sound Forms in Time opens with a section titled "The Falls Fight," a detailed, three-page report of a historical event: a 1676 raid into Indian territory that ends in a rout.[8] Hope Atherton, a Protestant minister, is separated from his fellow raiders and spends an unspecified period of time wandering in the wilderness before returning to colonial lands and his congregation. He dies soon afterwards. Despite the general lucidity of "The Falls Fight," on occasion Howe breaks into a more stumbling, repetitive, and speculative mode: "Putative author, premodern condition, presently present what future clamors for release?" (4).

The poem's second section, "Hope Atherton's Wanderings," accelerates the breakdown of conventional discourse. The section's strangely sedimented, misleading half-statements tend to confirm, rather than disprove, the charge of "being beside himself" that supposedly "occasioned" Atherton's written tale (5). Amidst this confusion, we discover several of Howe's disorienting word squares:

chaotic architect repudiate line Q confine lie link realm circle a euclidean curtail theme theme toll function coda severity whey crayon so distant grain scalp gnat carol omen Cur cornice zed primitive shad sac stone fur bray tub epoch too fum alter rude recess emblem sixty key (13)

Howe the "chaotic architect" presents us word-rubble so pulverized that if it operates as an "omen" or an "emblem" its significance is deeply obscured. She gives us language so stripped down, so denuded of syntax that a reader could essay it in any direction--horizontally, vertically, diagonally, or at random--without finding a path capable of arranging the word-nuggets into a coherent picture or narrative. The word-sequence "severity, whey, crayon," for instance, makes as much (or as little) logical sense as "severity, omen, tub." One cannot, though, dismiss Howe's word-array as arbitrary. She has limited her choices of words to a few isolable categories. One can discern traces of the Classical world: its mathematics ("circle a euclidean," "line Q"), architecture ("cornice"), and language ("Cur" means "why" in Latin). Another set of words impressionistically sketches a rural scene ("whey," "grain," "gnat," "shad," "fur," "bray," "tub"), a further set suggests stern value judgments ("repudiate," "severity," "primitive," "rude"), and yet another set enjoins particular kinds of artistic expression ("confine lie," "curtail theme," "toll function," "crayon so distant grain"). Moreover, a scheme, however perverse, evidently dictates the placement of these words: individual clusters possess strong consonance ("line, lie, link") or assonance ("scalp, gnat, carol"); one can detect a numerical ordering principle (the first three lines each contain nine elements, the last two lines ten); and the passage ends on something of a slant rhyme ("key" recalling "bray"). Nonetheless, these lineaments of order do not reduce but heighten the strangeness of the passage, since they provide little purchase for a reader intent upon deciphering it.

-

Critics have, nonetheless, persevered, striving to discover some

manner of commentary on Atherton's plight encrypted in the word

squares.[9] They have tried to pin down

these "most open apparitions":

is notion most open apparition past Halo view border redden possess remote so abstract life are lost spatio-temporal hum Maoris empirical Kantian a little lesson concatenation up tree fifty shower see step shot Immanence force to Mohegan (14)

If we imagine the word squares to be text "by," "about," or "from the point of view" of Atherton, the collapse of syntax inevitably leaves a reader with a multitude of questions. Fifty what? Trees, troops, or Indians? How does one "shoot Immanence"? With a camera? There are also perplexing anachronisms. Immanuel Kant was born five decades after the events that Howe recounts, and the Maori people were unknown to Europeans until after James Cook visited New Zealand in 1769.

- A persistent reader, though, can find residual traces of Atherton's story. Howe provides the barest sketches of the "spatio-temporal" coordinates within which historical narratives such as the clergyman's typically unfold. We have hints of a landscape ("tree," "remote") and perhaps a time of day ("view border redden"--sunset? dawn?). She gives us monosyllabic, vector-like indications of movement ("up," "step"). She indicates, too, the means by which those who have been "lost" try to find their bearings in new, foreign surroundings: by quantification ("fifty"), by induction ("empirical"), by deduction ("concatenation"), by schematization ("abstract"), and by observation ("see"). The more unusual words in the passage ("Kantian," "Mohegan," "Maoris," "Immanence," and "Halo") do not seem to represent agents so much as potential agents, or, better yet, word-nuggets around which sentences can or will take shape. One could easily project appropriately erudite asides concerning Hope's "excursion" (4) within which these words might appear: an anthropological comment on the place of immanence in Mohegan cosmology, perhaps, or an apt citation from Kant on the universal applicability of the categorical imperative even among the wild Maoris of New Zealand. This impression of growth-toward-discourse is reinforced by the moments in this odd passage where words begin to behave in a somewhat orderly syntactical fashion ("a little lesson," "most open apparition"). Such clusters suggest that these words are not only capable of generating conventional sentences but might already be in the process of doing so. Howe's word-grid seems to present a primordial matrix somehow just prior to historical narrative, a condition in which, although the "past" is still no more than a heterogeneous collection of words, it is nonetheless poised to emerge from gross quiddity into intelligibility.[10]

- Alternatively--but, curiously, without contradicting the above interpretation--Howe's word-array might be intended to depict language in a state of decomposition.[11] Howe could be presenting us with a scattering of language that we are supposed to interpret as the barest tracery of long-ago accounts of Hope Atherton's time in the wilderness. We are perhaps to intuit that these accounts are now a "story so / Gone" (6), that is, that they have subsequently been damaged, circulated in faulty copies, or lost altogether, known only through repute or hearsay. The peculiar spacing of the words in the passage beginning "is notion most open" would then be seeking to render visible the historical, entropic erasure that has afflicted what once might have been a set of reliable, detailed documents upon which to base a more conventional historical fiction. Howe, in other words, could be compensating for her inability to represent what has disappeared from the historical record by calling attention to the very fact of its vanishing.

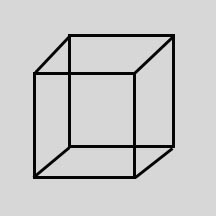

- Like a Necker cube, then, Howe's array beginning "is notion most open" plots an arrangement of nodes in two dimensions that can ambivalently suggest both protension and recession--that is, on the one hand, a process of maturation into rational discourse or, on the other hand, the decay away from it (see Figure 4). Not coincidentally, these impersonal, recalcitrant word-grids also appear just before Atherton concludes with a platitude-rich homily ("Loving Friends and Kindred:-- / When I look back / So short in charity and good works [...] . " [16]). The weirdly geometrical word-arrays mark, as it were, the furthest that Atherton ventures into the wilderness. Like Samuel Beckett in The Unnamable and Texts for Nothing, Howe situates us on the threshold where meaning abuts the incomprehensibility of the other-than-human.

- A close reading of Articulation of Sound Forms in Time can help us appreciate how word squares function--at least on one occasion. We learn little, though, about why Howe has chosen to figure an encounter with the non- or superhuman by mechanically arranging stubbornly particulate words into near-grids. If we are to understand when, how, and why her verse turns "postlinear" in the form of word squares, we will have to cast our net both more broadly and more deeply.

- Geoffrey O'Brien's remarkable series of reviews of Howe's work can serve as a useful point from which to begin fishing for answers. He struggles to articulate why he finds her verse both ineffable and oddly superficial. Her "haunting tunes," he asserts, seduce us by hinting that Truth, if not present here-and-now, nevertheless still exists: "Howe's words give the impression of echoing another, hidden poetry of which we catch only fragments, like an opera sung in another room [...] . The words are like magnetic filings that adhere uncertainly to a receding body of meaning" ("Meaningless" 11). These ghostly traces of a higher order of Being and Meaning seem sufficient to justify her use of resonant phrases that might otherwise seem laughable or irresponsible, such as "truth and glory" and "ideal city of immaculate beauty" ("Notes" 110). Howe's poetry can free a reader to enter into the terrain of the Ideal. She opens up "a world ([is] it ours?) in constant metamorphosis, a swirl of depths and tides, a series of transient landscapes (woods, seas, marshes) dissolving even as they [are] named."

- But O'Brien remarks that at other times, however, a reader can find access to these grand vistas impossible. The poetry then seems "hard, dry [...] spare, fragmented, analytical." What had seemed sublime insights couched in "Miltonic words" instead rather "brutally" turn out to be conjectures that "exist only in the mind" of the reader. "The interior spaces I'd glimpsed were not in the words but in their unstated connections: in the decisiveness and freedom with which the words were laid side by side, and the abysses which were permitted to open up between them." Howe's genius, O'Brien argues, lies in being able to write a fragmented poetry that is able to fulfill a desire for transcendence while also registering a cynical disbelief in it. In this ambivalent aesthetic, the "same word might be both opening and closure, reality and disguise, truth and a lie" ("The Way" 27).

-

Again we encounter a dual movement, as with the Necker cube-like

movement into and out of the discourse of history exhibited by the word

squares in Articulation of Sound Forms in Time. O'Brien,

however, helps us see that this doubling is fundamental to Howe's writing

more generally. A concrete--and visually conventional--example can help

clarify Howe's habitual practice of making two readings equally available

("All things double"--ASFT 28), as well as demonstrate what

she gains by writing in such a manner. Stephen-Paul Martin, in his essay

"Endless Protean Linkages," comments upon Howe's terse précis of

the Tristram and Iseult myth in Defenestration of Prague:

Martin chooses to read Howe's invocation of Iseult as if the poet were a feminist theorist bent on dismantling patriarchal ideology:Iseult of Ireland Iseult of the snow-white hand Iseult seaward gazing (pale secret fair) allegorical Tristram his knights are at war Sleet whips the page (DP 100)

We are not given the opportunity to lose ourselves in the glamor of "one of the world's greatest love stories." We are instead asked to see the "play of forces" that underscores it. Iseult is the conventional female "seaward gazing," pining for her lost lover. She is "(pale secret fair)," a mere feminine signifier who has all the qualities normally assigned to women in medieval legends or romances. Tristram is the masculine signifier, the "allegorical" warrior. In the original romance (and in the countless versions of it that have come down to us through the centuries) we are encouraged to think of Tristram and Iseult as "real" flesh-and-blood human beings. But Howe shows us what they actually are: patriarchal conventions, stick figures used to convey an ideological message under the guise of storytelling. When Howe tells us that "Sleet whips the page," she reminds us that the climate Tristram and Iseult inhabit is a fictive space whose purposes can and should be analyzed. (64-65)

Martin's interpretation has a great deal of merit. Iseult and Tristram appear only once in Defenestration of Prague, in this brief vignette, and they can indeed seem rather like "stick figures" trotted out and dismissed in a satiric pageant. Howe's perpetual insistence on the fictive character of poetry ("a true world / fictively constructed"--PS 54) and on the materiality of the text do lay bare the workings of her verse to such an extent that it is hard to ignore the writerly artifice that culminates in what we see on the page. What Martin finds true of Defenestration of Prague's Iseult is even more evident in the opening lines of Howe's 1999 work Rückenfigur:Iseult stands at Tintagel

Howe, in her brevity, seems to mock the elaborate atmospherics that often cue the introduction of a heroine in a novel or a romance. Here we discover no white dress, no ivory skin, no deep shadows nor silent, dark night--just a telegraphic indication of "light and dark symbolism." Readers are coyly instructed to fill in the blanks with appropriate tropes. They thereby become complicitous in the mechanics and the production of the poem. And, if we are to believe Brecht and Benjamin, this kind of theatricalization of the artistic process operates in service of ideological critique by jolting an audience out of its customary passivity.[12] From this point of view, then, one can say that these schematic, cursory invocations of the Tristram story illustrate the "brutality" of Howe's analytic mind as she probes the unsightly innards of literary tradition.on the mid stairs between

light and dark symbolism (129)

- But is Howe's Iseult just a stick figure? "Iseult stands at Tintagel": although it may sound brisk or even martial, for an informed reader the opening line of "Rückenfigur" can nonetheless strike a powerful chord. It evokes "Iseult at Tintagel," the fifth book of Algernon Charles Swinburne's Tristram of Lyonesse.[13] "Iseult at Tintagel" is one of the most extravagant of lovers' plaints in English. The disconsolate Iseult, aria-like, recounts her grief, passion, and pain. She begs God to damn her if that sacrifice might spare her lover the same fate. She praises and abuses the absent Tristram to the accompaniment of a storm at sea. "Iseult stands at Tintagel / on the mid stairs between / light and dark symbolism." In Swinburne's Tristram, Iseult's dramatic monologue revolves obsessively around tropes of light and dark and their horrifying failure to remain distinct: "dawn was as dawn of night / And noon as night's noon" (94). Good and evil, heaven and hell, morn and eve--to the suffering soul, all such divisions are meaningless ("soul-sick till day be done, and weary till day rises" [97]). For a reader familiar with Tristram of Lyonesse, Howe's statement that "Iseult stands [...] between light and dark symbolism" is not satirical. It recalls a precursor poet writing magnificent verse at the height of his career. "Rückenfigur" could hardly begin on a more explosive note.

- Full or empty? Iseult and Tristram as names wonderfully redolent of myth and literary tradition, or as stick figures acting out tradition's desiccation? Howe seems deliberately to make multiple, if contradictory, readings available to her audience.[14] In this respect, her verse resembles the optical illusions made famous by Gestalt psychologists--the rabbit-duck drawing, the young-old woman, the profiles-goblet puzzle. In each of these instances, a viewer can readily see one or the other option (rabbit or duck, young or old woman) but cannot easily see both simultaneously. The only place where both options coexist harmoniously is in the design of the artwork itself.[15] Similarly, Howe's Iseult is just a stick figure. Sometimes. Other times she comes trailing clouds of glory. It depends on one's point of view.

-

As O'Brien's reviews show, this dynamic is especially

disconcerting in Howe's poetry because she puts transcendence itself up

for grabs. At almost every point in her work she can be read as

critiquing and or offering access to Truth. In other words,

the existence of a transcendental referent is perpetually put into doubt

even as, paradoxically, that same existence is celebrated. The markedly

undialectical character of this worldview is not unusual in the broader

context of late twentieth-century literature. Linda Hutcheon contends

that postmodern literature is, properly speaking, "neither 'unificatory'

nor 'contradictionist' in a Marxist dialectical sense":

the visible paradoxes of the postmodern do not mask any hidden unity which analysis can reveal. Its irreconcilable incompatibilities are the very bases upon which the problematized discourses of postmodernism emerge [...] The differences that these contradictions foreground should not be dissipated. While unresolved paradoxes may be unsatisfying to those in need of absolute and final answers, to postmodernist thinkers and artists they have been the source of intellectual energy that has provoked new articulations of the postmodern condition. (21)

In making this argument, Hutcheon has in mind the unresolved/irresolvable tension between fiction and history common in the contemporary novels that are her proximate subject. Although Howe's poetry likewise mixes history and fiction, the un-dialectical "irreconcilable incompatibilities" in her work are so pervasive, in form as well as content, that its bipolarity seems to represent a sharp intensification of Hutcheon's dynamic. From the microlevel of the line to the macrolevel of the long poem, Howe continually offers repleteness and/or emptiness, the skeptical and/or the visionary, Eden and/or Gethsemane. Moreover, the duality in Howe's poetry is born neither of paranoia nor of paralyzing doubt. She does not plunge us into a regio dissimilitudinis in which we cannot distinguish true and false. Rather, we have the option of apprehending the true and/or the false while still wandering in the Dantean dark wood--a surprisingly optimistic prospect, all things told. In contrast to Hutcheon's account, the "unresolved paradoxes" at the heart of her poetics do not inevitably and always frustrate "those in need of absolute and final answers." Howe grants them the right to choose to read her words as revelation. Skeptics and believers can agree that Howe pierces the Veil of the Temple. The question is whether one decides to see nothing, or something, on the Veil's other side. - A duck-rabbit combination of skepticism and transcendentalism is such a foundational part of Howe's worldview that one can trace it back to her earliest works. In her case, though, such a recounting takes us back into the years before she chose poetry as a vocation. Howe was in her forties before her first chapbook appeared. A graduate of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School, she spent the late 1960s and early 1970s actively involved in the New York art world. By examining this early, under-studied phase in her career, one gains insight into the origins of her visual poetics and into the intense, ambivalent spirituality that subtends them.

- The Susan Howe Archive at the University of California, San Diego preserves written instructions, ephemera, photographs, and other materials relating to Howe's installations of 1969-1971, which possessed such evocative names as Long Away Lightly, On the Highest Hill, and Wind Shift / Frost Smoke / Malachite Green / Rushlight.[16] These installations contained a heterogeneous mix of word and image: original verse; extracts from ecological and geological texts; extracts from historical sources; illustrations excised from books and journals; photographs; and Xerox copies. Howe mounted or pinned these diverse objects to paper, wood, or cloth supports according to precisely determined measurements.[17] She also typically added a few lines or rectangles with tape or pigment and, occasionally, blots of thinned paint.

- Howe's installations were harshly rectilinear. The constituent polygons, cut-outs, and text blocks were uniformly rectangular, and the assorted elements in each installation were distributed as if they occupied coordinates on a Cartesian grid as well as aligned perfectly with implied horizontal and vertical axes. The often flimsy, always unframed supports were attached directly to blank expanses of wall. Finally, Howe left the vast majority of her supports untouched and uncovered. From any distance greater than arm's length, one would have experienced these installations as fields of whiteness, interrupted by images too small to identify and short pieces of writing too distant to read.

- Significantly, as seen in the few photographs that document Howe's actual exhibitions, the installations looked like her later word squares. One particularly suggestive (alas unidentified) photograph depicts a wall upon which Howe has hung nine rectangular pieces of what seems to be paper in the pattern of a tic-tac-toe board. Each piece of paper features images, texts, or a combination of the two, positioned, of course, on an implied grid. The rightmost piece of paper in the middle row has nine, very short statements or passages of verse arrayed, again, in a tic-tac-toe-like pattern, this time spread out across a veritable sea of white space.[18]

-

Howe's 1969-71 installations are very much of their time and

place. Their understatement, relentless geometry, reliance on the

written word, and recycling of banal, mass-produced images speak to her

loose ties to Conceptual Art, more specifically to her then-fascination

with the work of Robert Smithson.[19]

Like Smithson, she mixes the creative and the documentary, intersperses

poetic and scientific language, and makes use of deceptively "boring"

images, mostly monochrome or sepia-tone reproductions cut haphazardly out

of journals or books. She does, however, diverge from Smithson (and

other contemporary conceptual artists) in several respects. First, she

incorporates fiercely romantic verse into her installations, such as the

following:

on the highest hill of the heart

The moral here is conventional: that one's interior life is like a landscape and that, moreover, this landscape is an archetypal one, buffeted by "ancient" forces and offering no solace as one peers into the "west" and sees the "strand" of one's future trailing into the "slaty gray" emptiness and twilight that portend death. The play throughout the lyric on the letters "s" and "t," though, is effective, and, in such a short poem, the three parallel phrases "keen winds cut," "long strand glints," and "heart's sea shivers" offer a marvelously heavy, decisive rebuttal to the Swinburnian lilt of the opening, anapestic line. Howe's versecraft, even at this early stage, is incomparably superior to Smithson's, whose pale imitations of Allen Ginsberg he rightly never published.[21] Moreover, Howe does not satirize romantic longings in the manner of Smithson, whose contemporary piece "Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan" (1969) verges on the carnivalesque in its Beat-like, half-parodic celebration of Mayan cosmology. Instead, Howe subtly ironizes her poetry by submerging it in an oceanic "swash" of space. Blankness overwhelms expression; the indifferent white reduces a speaker's emotions, whether melancholy or ecstatic, to minor, arabesque-like details on an otherwise uniform surface.

the keen wind cuts

ancientwest through the slaty gray of space swash

the long strand glints

stalestars stars stars stars

the heart's sea shivers[20]

-

To explain Howe's plentiful use of white space, one has to look beyond

her overt debts to conceptualism. It speaks to a powerfully quietist

strain in her aesthetics that aligns her also with another canon of

avant-garde artists, as a 1995 interview makes clear:

Q. [An earlier interview] ends with your statement that if you had to paint your writing, "It would be blank. It would be a white canvas. White." I wondered if you could explain what you meant to suggest with that wonderfully evocative remark.

Howe's choice of "minimalist" heroes provides a context for her swerve away from Smithson's aesthetic by underscoring the fact that she never really shared his passion for the muck, mess, and fracture of the natural world. Ad Reinhardt is best known for his "black paintings," which are three-by-three grids of black squares that differ ever so slightly in luster and hue.[22] Agnes Martin is best known for her six-foot-by-six-foot canvases covered with tiny rectangles. Robert Ryman is best known for restricting his palette to the color white.[23] As her comments illustrate, Howe admires this particular set of painters for a specific reason: their art posits that the unsaid, the unpainted, can "suggest" the infinite more effectively than any attempt to represent it directly. Martin, Reinhardt, and Ryman reduce their painterly subject matter to a degree zero, a mere grid or a single pigment, in order to redirect a viewer's attention to the vertiginous freedom that precedes any artistic gesture. Howe makes an analogy between her poetry and their art, seeing in the two kinds of material support--the page and the canvas--an intimation of an Absolute, pure and virginal, that precedes human endeavor and activity. The task of the poet and the painter alike is to let that primal "whiteness" shine out.A. Well, that statement springs from my love for minimalist painting and sculpture. Going all the way back to Malevich writing on suprematism. Then to Ad Reinhardt's writing about art and to his painting. To the work of Agnes Martin, of Robert Ryman [...] I can't express how important Agnes Martin was to me at the point when I was shifting from painting to poetry. The combination in Martin's work, say, of being spare and infinitely suggestive at the same time characterizes the art I respond to. And in poetry I am concerned with the space of the page apart from the words on it. I would say that the most beautiful thing of all is a page before the word interrupts it. A Robert Ryman white painting is there [...] Infinitely open and anything possible. (Howe, Interview with Keller 7)

- Recognizing this principle can help one appreciate Howe's later liberal use of white space in her poetry. She has a habit of including pages in her long poems that consist of no more than a handful of words isolated in the center of a page.[24] These words often look paltry or whispered, certainly chastened. In the small-press edition of Articulation of Sound Forms in Time, for instance, the phrases so treated are "Otherworld light into fable / Best plays are secret plays."[25] The "Otherworld light" refers, at least in part, to the primal whiteness of the page that Howe has rendered so noticeable. This whiteness thereby enters "into fable," in other words, into Hope Atherton's story. It does so, however, as a "secret," since in its pure potentiality it cannot be directly articulated--attempting to do so would grant it determinate form, hence violating the very open-endedness that made it valuable in the first place. "Best plays are secret plays."

- Howe's love for white space alone does not, however, explain her persistent preference for the rectilinear: squares, arrays, grids. Howe's favored "minimalists," though, all share her infatuation with grids, and by turning to an art critic who has famously written on this topic--Rosalind Krauss--we can begin to appreciate why rectilinearity proved essential to Howe's developing aesthetic and spiritual sensibilities.

- In her classic essay "Grids"--in which Reinhardt, Martin, and Ryman all make appearances--Rosalind Krauss takes up the problem of the insistent recurrence of grid-like patterns in modern and postmodern visual art. She claims for it a covert ideological role. As she sees it, artist after artist, from Piet Mondrian to Frank Stella to Andy Warhol to Sol LeWitt, discovers in the grid's geometry a way of circumventing the age-old, ever-vexatious split between spirit and matter. That is, grids look scientific, like a return to the mathematical rigor that typified such Renaissance breakthroughs as vanishing-point perspective, but they also represent pure abstraction, an escape to the realm of universals. "The grid's mythic power," she writes, "is that it makes us able to think we are dealing with materialism (or sometimes science, or logic) while at the same time it provides us with a release into belief (illusion, or fiction)" (Originality 10).

- Krauss would probably diagnose Susan Howe as another victim of the grid's insidious appeal--as well as object strenuously to Howe's use of the word "minimalist" to refer to artists who likewise fall prey to the grid's magic. An art historian who has written on 1960s and 70s minimalism as a phenomenological revolution in the arts, Krauss would likely contend that Howe fixates on the most backward, "modernist" aspects of the movement.[26] In fact, although Reinhardt and Martin are frequently labeled minimalists because of their limited, geometrical subject matter, a critic such as Krauss is liable to argue that they are better understood within the context of Abstract Expressionism. Reinhardt, after all, belongs to the same generation as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, and Martin explicitly styles herself as Barnett Newman's heir.[27] Their grid-paintings are legible as acts of spiritual, aesthetic askesis, and they convey a sublimity entirely foreign to the post-Pop, cool sensibility of most late-1960s avant-garde art. In terms of affect, Reinhardt's and Martin's best paintings belong in the same class as Newman's Stations of the Cross and the Rothko Chapel.[28]

- Accordingly, Krauss has written an essay, "The /Cloud/," which presents Agnes Martin's grids as an endgame in a senescent modernist tradition, not as a postmodern breakthrough. Whereas early-century grids by masters such as Piet Mondrian were able to resolve (that is, repress) the spirit/matter split through the creation of a single image, later artists discovered that grid-paintings no longer possessed that same "magical" potency. Over the years, grids gradually lost their original, spiritual force as a consequence of having become too closely associated--by critics and viewers alike--with the materiality of the canvas (164-65). Agnes Martin, according to Krauss, is unique in having found a way to revitalize an increasingly moribund device. To illustrate this fact, Krauss dwells on a curious feature of Martin's paintings. Up close, one concentrates chiefly on the "tactile" qualities of her work: the tracery of the lines and the weave of the canvas. As one moves back, however, something odd happens. The canvas seems to dissolve into a haze or a mist, observable from any vantage, as with clouds, seas, or fields. One also has an experience of radiance, or directionless illumination. This middle distance is characterized by "illusion" and "atmosphere." As one moves further away, though, the illusion collapses. The "painting closes down entirely," and in its "opacity" it resembles a "wall-like stele" (158-59). Krauss marvels at the "closed system" that Martin thereby creates. The two "materialist extremes"--the fabric of the grid, as seen up close, and the impassive panel, as seen from a distance--frame the transcendent "opticality" of the middle distance. Whereas modernist grids, such as Mondrian's, seek to express transcendence and materiality simultaneously, Martin renders those two qualities a function of a viewer's position vis-á-vis the canvas (164-65).[29]

- Krauss's "The /Cloud/" may have been conceived as an unflattering critique of Martin's outmoded high modernist aesthetic, but, as with Krauss's essay "Grids," "The /Cloud/" is nonetheless most illuminating in the present, literary context. Howe, like Martin, separates out the spiritual and material aspects of her art. Howe, like Martin, makes her audience's choice between the two a function of point of view, not a question of authorial intent. Thus, insofar as they are modeled on Agnes Martin's paintings, one begins to see how Howe's own "grids," her word squares, might function as an extension of her duck-rabbit aesthetic. They prove ambivalently materialist and/or idealist.

- Howe's comments on Martin can further refine this comparison. Not only does Howe credit Martin with being instrumental in her transition from painting to poetry, she verges on calling Martin herself a poet: "I remember a show Agnes Martin had at the Greene Gallery--small minimalist paintings, but each one had a title; it fascinated me how the title affected my reading of the lines and colors. I guess to me they were poems even then" (4). How, though, can a Martin painting be a "poem," by any but the loosest definition? There are no words in a work by Martin, only rectangles. Can a title alone qualify a painting as a poem? As we have already seen, Howe pinpoints Martin's ability to be "spare yet suggestive" as her defining characteristic. If a single word can completely alter the experience of a painting, then ought it qualify as a "minimalist" poem? Howe has argued something of the sort about a scrap of paper upon which Emily Dickinson wrote a single word: "Augustly" (BM 143). The contention that an isolated word can be a poem dovetails with Howe's duck-rabbit outlook. "Augustly" could either be an infinitely evocative word--or a word reduced to its bare quiddity.

-

What, one then wonders, were the poem-words that rendered Agnes

Martin's canvases so memorable? In her anecdote about the Greene

Gallery, Howe does not mention specific titles, but one can make a

reasonable guess. Howe's transition from painting to poetry occurred in

the early 1970s. Agnes Martin's career happens to contain a long hiatus,

from 1967 to 1974, during which time she either was traveling or living

as a hermit in New Mexico, although her works continued to be exhibited

and her fame continued to grow. In the years leading up to the

publication of Howe's first book, Hinge Picture, the poet would

have known Martin primarily through her paintings of 1960-67, the ones

most frequently seen in galleries at the time. These early works are

notable for the recurrent use of two kinds of titles. A first set has marine monikers, such as Islands No. 1,

Ocean Water, The Wave, and Night Sea. A

second set of paintings has linguistic labels, such as

Words and Song. These two classes of names

enshrine Martin's response upon completing her first grid drawing:

"First I thought it was just like the sea [...] then I thought it was

like singing!" (Chave 144). In the catalog for her 1973 Philadelphia

retrospective, the painter further comments,

The ocean is deathless

Martin, it seems, hopes that her grid paintings give access to a timeless, spiritual realm that resembles an ocean, or silent speech. One can see why this aspect of Martin's art might so forcefully capture Howe's imagination. A single word or a phrase transforms a flat canvas into a doorway into a limitless wonderland of silent singing or washing waves.

The islands rise and die

Quietly come, quietly go

A silent swaying breathI wish the idea of time would drain out of my cells and leave me quiet even on this shore. ("Selected" 26)

- Agnes Martin, as understood first through Krauss's "The /Cloud/" and second through the clues that Howe gives us, can be read as offering Howe a poetics in germ. Martin's bipolar paintings represent a combination of vision and/or Vision, words and/or Silence, faktura and/or ecstasy. Which of these two paired terms is in the dominant depends, not on the artwork, but upon the viewer's position in regards to it. Furthermore, Martin's paintings suggest that poetic grids can grant an entrée to a sublime landscape, the "deathless" ocean, which is somehow interchangeable with "words" and "song."

- Questions remain, though. Can one really transpose a painterly technique into another medium--language--without losing something essential? Also: Howe may think of a single word as a mini-poem, but she nonetheless characteristically writes long poems, and her word squares contain many heterogeneous elements. To explain how Martin's painterly sensibility relates to Howe's mature visual poetics, we need a better understanding of the route by which Howe made the transition from painter to poet.

- During the early 1970s, finding her work more and more occupying the borderlands between the visual and literary arts, Howe sensibly began corresponding regularly with one of that region's few éminences grises: Ian Hamilton Finlay, a Scottish poet, sculptor, and publisher who did much to popularize Concrete Poetry in the English-speaking world. Finlay happily played Chiron to her Jason.[30] This period of literary apprenticeship culminated in a 1974 article, "The End of Art," which John Palatella has characterized as a veiled manifesto "mapping a genealogy of [Howe's] aesthetic" (74). In "The End of Art" Howe proposes fundamental connections between Finlay's poetry and the art of one of her minimalist heroes, Ad Reinhardt. Both, she claims, teach the same lesson: "to search for infinity inside simplicity will be to find simplicity alive with messages" (7).

- Given Howe's enthusiastic endorsement of Finlay in the same breath with one of her favorite painters, it is plausible to conclude that Finlay's work might provide the missing link between Martin's painterly grids and Howe's poetic equivalent, her word squares. But as John Palatella warns, it is not immediately apparent whether the man who made such famous works as Wave-Rock influenced Howe's poetry in any measurable way, beyond, perhaps, reinforcing her interest in the materiality of the word and her distaste for conventional syntax (76). Some of Finlay's poems, "Acrobats" for instance, could be called word squares, but they are ultimately closer to a stand-up comedian's one-liners than the mysterious arrays of shattered words that one finds in Howe (see Figure 5).

I would argue that the crucial lesson Howe learned from Finlay was in the first instance thematic and only secondarily formal--the inverse of what one might expect, given Concrete Poetry's reputation for sacrificing complexity of content in order to cultivate instantaneous perceptual effects. In the case of Finlay, that reputation is wholly unmerited. Among much else, he is a poet with an enduring passion for the ocean. Fishing boat names and registrations, for example, supply the words used in his "Sea Poppy" series, and references to boats and nets abound in his work down to the present day.[31] In addition, his love for the sea has influenced not only his choice of subject matter but also his poetry's look. Again and again, Finlay recycles an implicit equation between page and sea that he borrows from a foundational text for much twentieth-century visual poetry, Stéphane Mallarmé's Un Coup de dés. Un Coup de dés repeatedly compares its own lines, scattered across wide expanses of white space, to a plume of foam on the sea, or to the wreckage of a ship breaking apart in a storm.[32] Variations on Mallarmé's conceit occur in such Finlay works as "drifter," in which names for kinds of ships are positioned rather arbitrarily in "oceanic" white space, and in the octagonal poem-sculpture, Fisherman's Cross (see Figure 6).

- Howe's "The End of Art" contains a passage of superb

commentary on

Fisherman's Cross.[33]

After praising Finlay for having bettered Mallarmé, she writes,

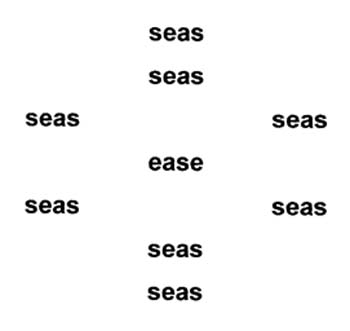

The two words, seas and ease, are as close in value as two slightly different blacks are close. Here the words are close visually and rhythmically. The ea combination in the middle is in my memory as the ea in eat, ear, hear, cease, release, death, and east, where the sun rises. These are open words and the things they name are open. There are no vertical letters, just as there are no sharp sounds to pull the ear or eye up or down. Life (seas) rhymes with Death (ease). The cross made by the words has been placed inside a hexagonal form which blurs the edges. The eye wanders off toward the borders until ease (almost seas backward), in the center, draws it back as does sleep, or death, or the sea. (6)

Words emerging from the deep. People sinking into the sea, as into death. Finlay is one of a long line of poets--including Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, and Wallace Stevens--who feel compelled to meditate on the mystery of the sea, genetrix and destroyer.[34] - Howe is fully in sympathy with this point of view. The ocean is

one of her favorite images. It appears in virtually all of her poems to

date.[35] She has gone so far as to

say, "the sea and poetry [...] for me they are one and the same"

(Howe, Interview with Keller 29). Her prose, too, is full of references to the

ocean, and she frequently weaves into her argument other writers'

statements on the subject.[36] There

are biographical reasons for Howe's abiding interest in the sea--chiefly

her Transatlantic upbringing and her late husband's life-long

involvement with ships and ship-building[37]--but the ocean usually enters her poetry as an

impersonal archetype.[38] Among the

many guises that the sea adopts in her work, the following are the most

significant:

- Chaos. The sea is a place of storms and pirates. It represents the blind violence that governs the course of history.[39]

- Genesis. The sea is a place of origin. It is the First Cause that gives rise to sound, to soul, to language and poetry.[40]

- Pax. The sea is a place of silence and unutterable peace.[41]

- Peregrinatio. The sea is a place of exile, transit, drift, and pilgrimage, much as in Anglo-Saxon elegy.[42]

- Thanatos. The sea is a place of death. It is where one dies, and it is either the avenue to, or the abode of, the dead.[43]

Howe undoubtedly derives her mythology of the sea from a wide variety of literary sources, from the Bible to Moby Dick to Olson's Maximus Poems, but she learns two invaluable lessons from Finlay's particular inflection of this tradition. First is an association between the page and the ocean, and, further, the sense that words float upon, or emerge from, the ocean-page. Although two-dimensional, the page is, like the surface of the sea, a thin, variegated skin concealing depths upon "seacret" depths (EB 75). A written work is no more than a "Text of traces crossing orient // and occident" the "empyrean ocean" of white space (PS 56). As we have already seen, Howe considers the blank page expressive of an infinity comparable to that intimated by Agnes Martin and Ad Reinhardt. For Howe, the ocean is a figure that allows her to conceptualize, to discuss, and to gesture toward that primal and final absolute.

-

The second lesson that Howe learns from Finlay is an appreciation

for the gap between poetry and painting. In "The End of Art" she writes

that "silence" is the only adequate response to a Reinhardt black

painting (2). In contrast, Fisherman's Cross may resemble a

Reinhardt work on account of its use of the cross as a structuring

principle and its symmetry and simplicity, but Finlay's

poem-sculpture uses words as its building blocks and hence introduces the

problem of sound. Hence, in her interpretation of Fisherman's

Cross, she lingers over the vowel combination "ea" and over the

"rhyme" that the poem proposes between "Life (seas)" and "Death (ease)."

In her 1995 interview with Lynn Keller--the same interview in which she

discusses her debts to Finlay, Martin, and Reinhardt --Howe again singles

out the distinction between the absence and presence of sound as the

crucial dividing line between the visual and written arts. She asserts

that she forever crossed over from "drawing" into "writing"

once she began to think about the aural impact of the words she had

been using in her painting.

I moved into writing physically because this was concerned with gesture, the mark of the hand and pen or pencil, the connection between eye and hand [...] There is another, more unconscious element here, of course: the mark as an acoustic signal or charge. I think you go one way or another--towards drawing or towards having words sound the meaning. Somehow I went the second way and began writing. (6)

From the 1970s to the 1990s, Howe has emphasized the role that sound plays in her work. At almost every opportunity, she asserts that it determines the shape and character of each line she writes, both in verse and prose.[44] When at the "cross"-roads between Reinhardt's silence and Finlay's sound, she decisively opted to pursue the latter path. -

The two lessons that Howe learns from Finlay--about the look of

the page and about its intrinsically aural character--govern her use of

the open ocean as a figure for the creation, or emergence, of art from

the matrix of infinity. Although writers since Antiquity have used

encounters with the ocean as a myth of origins, traditionally, as in

Swinburne's "Thalassian" and Whitman's "Out of the Cradle Endlessly

Rocking," the roar of the waves at seaside is the proximate

cause for a poet's desire to write. Howe, too, writes about seashores,[45] but for her the wide expanses of the

ocean-wilderness--the terrain of Fisherman's Cross--hold the

ultimate allure. The "Unconfined [...] ocean" (MM 146) is

her personal symbol of sublimity, and to plunge into it entails great

risk but can also yield revelation. "Out of deep drowning," she writes,

comes "prophetical / knowledge" (DP 88). But she also

contends that gaining "prophetical knowledge" does not, in itself, make

one a prophet. That knowledge must first be brought ashore. One has to

give up the "ease" of the sea's deathly quiet and re-enter the

babble-roar of the human world. She hints at this transition from

silence into speech in "Sorting Facts":

In English mole can mean, aside from a burrowing mammal, a mound or massive work formed of masonry and large stones or earth laid in the sea as a pier or breakwater. Thoreau calls a pier a "noble mole" because the sea is silent but as waves wash against and around it they sound and sound is language.[46] (319)

If one does not return from sea to land--if the obdurate concreteness of the earth does not force Language-Ocean to yield up the "thud" of language (PS 53)--the result, as Howe tells Edward Foster in her Talisman interview, is tantamount to death:If you follow the lure of the silence beyond the waves washing, you may enter the sea and drown. It's like Christ saying if you follow me, you give up your family, you have no family [...] If you follow the words to a certain extent, you may never come back. (BM 178)

Finlay's poetry, especially Fisherman's Cross, instructs Howe how she might go about integrating these concepts into the very manner in which she wrote a poem. "Disciples are fishermen / Go to them for direction" (SWS 35). While writing and arranging her words on the page-sea, she can think of them as ones cast up from the deeps, written by a "foam pen" (L 204). This "brine testimony" (R 131), or "water-mark" (EB 63), is like a "raft in the drift" (DP 117) on the white of the page. Moreover, it may only be an "ebbing and nether / veiled Venus" (DP 128), more "wrack" (MM 145) and "broken oar or spar" (L 168) than epiphany on the half shell, but Howe, having "rowed as never woman rowed / rowed as never woman rowed" (L 168), is able to offer up at least "the echoing valediction / of [...] gods crossing / and re-crossing" (H 52). - Crosses, echoes, waves--the building blocks are now in place to

answer the remaining questions posed by Susan Howe's word squares.

Krauss would have us believe that grids as a structuring device

in art are calculated to suppress history and magically harmonize urges

toward immersion in the material world and urges to escape it. Howe

certainly writes as if her own word squares, and her poetry more

generally, conflate the material presence of the word (its sound/its

appearance) and an experience of the transcendental. "A poet sees arrays

of sound in perfection," Howe has written ("Women" 84), and on other

occasions she has claimed that these perfect arrays of sound come to her

from another, timeless plane of existence.[47]

Writing [...] is never an end in itself but is in the service of something out of the world--God or the Word, a supreme Fiction. This central mystery--this huge Imagination of one form is both a lyric thing and a great "secresie," on the unbeaten way [...] A poet tries to sound every part.

"Echoes of a place of first love"--Howe alludes to Robert Duncan's signature poem, "The Opening of the Field," in which he talks of returning to "the place of first permission" (Opening 7). One could, therefore, read Howe as a Duncan-style poet-mystic who desires her readers "to enter the mystery of language, and to follow words where they lead, to let language lead them" (Howe, Interview with Keller 31). Howe's word squares assuredly do seem designed to open out into infinite possibility and into the unknown. With gnosis wrested from the heart of the sea, Howe comes to us: "I messenger of Power / salt-errand / sea-girt" (DP 96).Sound is part of the mystery. But sounds are only the echoes of a place of first love [...] I am part of one Imagination and the justice of Its ways may seem arbitrary but I have to follow Its voice. Sound is a key to the untranslatable hidden cause. It is the cause. ("Difficulties" 21)

- But this is not the whole story. As we saw with Howe's use of the Tristan myth, at every point in her work transcendental impulses coexist with their antitheses. As Möckel-Rieke has put it, Howe is uniformly contradictory, "teilweise strukturalistische, teilweise sprachmystische" (281). That is, if she is part speech-mystic, she also provides a structural anatomy of mysticism. One can witness this dynamic at work in her word squares, which do serve a definite analytical purpose. As we have seen in Articulation of Sound Forms in Time, they fail to present coherent narratives, and they fail to provide access to a stable "fictive world." Instead, Howe seems to "spread [...] words and words we can never touch hovering around subconscious life where enunciation is born" ("Ether" 119). She gives us not an enoncé, a statement concerning a defined topic, but rather a model of the process of "enunciation" itself.

-

Having explored the relation between Howe and Finlay, we have a means for specifying further how Howe

conceptualizes this process of "enunciation." She frequently relies on

an implicit metaphor between the page and the ocean. It is possible to

say that in her word squares we observe words birthing from an

ocean-matrix. But, as Howe's comments about oceans reveal, this womb is

a blank. An emptiness. "Loveless and sleepless the sea"

(SWS 42) she cautions us, mere

This empty sea cannot, stricto sensu, be "seen." That is, it contains, and is, nothing, and one cannot see what does not exist. Sight, and sound, can properly be said to belong only on this side of the land/ocean divide, in the realm of history and humanity. The world prior to, or beneath the level of, consciousness is an effect of writing as if such a thing existed, a point Howe makes at the conclusion of sequence Rückenfigur:deep dead waves wher when I wende and wake how far I writ I can not see (L 164)

Following this logic, the "spars" and "echoes" in the word squares are like "veils" that conceal nothing. They are, however, calculated to give the impression of Someone behind them. They are attempts at "Theomimesis," at miming an absent God.Theomimesis divinity message I have loved come veiling Lyrists come veil come lure echo remnant sentence spar (144)

- When read aright, then, the "timeless place of existence" that Howe claims as the origin of her poetry does indeed turn out to be a "Supreme Fiction"--"fiction" understood in its original Latin sense as "something made." Her word squares gesture toward an eternity that cannot pre-exist the act of writing or antedate the onset of history. "For me there was no silence before armies" (Europe 9). Jacques Derrida's musings on the topic of "spacing" in his essay "Différance" can help clarify this point. Spacing, Derrida contends, is at once a spatial and a temporal process. An artificer introduces spaces--introduces emptiness, or "difference"--into a system in order to give it a defined spatial form. But the act of spacing is itself a temporal process, that is, an act. And a viewer necessarily takes in this spatial form in time, that is, by looking from node to node and observing their configuration (Margins 7-9). Derrida would agree with Rosalind Krauss that an array, by organizing space, strives to render time an extrinsic variable and thereby approximate a timeless Form. But Derrida would also go on to say that an array's dependence on the act and consequences of "spacing" inescapably imports temporality back into its very structure and thus vitiates its aspiration to represent eternity (13).

- This deconstructive critique comes naturally to Howe. One of her recurrent themes is the inseparability of space and time.[48] "Concerning a voice through air // it takes space to fold time in feeling," she writes in a recent essay ("Sorting" 302), and in a review of John Taggart's work, she praises him for understanding that true poets have "visions of how one might articulate space in an audible way" ("Light in Darkness" 138).[49] The wonderfully ambiguous title of her long poem Articulation of Sound Forms in Time (is "forms" a noun or verb? "sound" an adjective or noun? "in time" as in "just in time"?) can be read as a concise expression of her belief that poetry, "sound forms," are articulated within history, "in time," and not outside of it.[50] "Our ears enclose us," Howe reminds us,[51] and even if we are bent on "the mind's absolute ideality," in daily life "stray voices / Stray voices without bodies // Stray sense and sentences // Concerning the historicity of history" will penetrate our contemplation of things timeless (H 54).

- Howe's word squares draw a reader's attention toward the white space of the page in order (1) to intimate the Void out of which the perceptible world arises and (2) to expose that primordial nothingness as a fraud, or, more precisely, as a "fiction" arising from a certain use of words. For her, the page's white space is the deathless ocean--the Void/the divine/Language--and the words are like the evanescent sea foam that rides upon it. The messiness of Howe's word squares is a consequence of her awareness that poetry comes into being in time, that is, in the fallen world. Howe's word squares all appear at particularly momentous points in her poetry, typically at the beginning or end of a work, or, in the case of The Liberties, when an author-figure is stripped of his or her social identity and confronts the linguistic and phenomenological grounds of selfhood.[52] The word squares mark the limits of the humanly knowable, and they indicate that beyond those limits lies God--if we choose to believe that (S)he exists.

- Surveying contemporary English-language verse, one will occasionally run into word squares in writings by authors other than Howe. Variations on the device appear, for example, in Christian Bök's Crystallography, Kathleen Fraser's il cuore, Jorie Graham's Swarm, Myung Mi Kim's Dura, Darren Wershler-Henry's Nicholodeon, and C.D. Wright's Tremble. Do these poets, too, give us sprays of catachrestic coinages afloat on a page-ocean?[53]

-

One cannot make that assumption. Take the case of Myung Mi Kim:

her long poem Dura is, among other things, a

Korean-American's meditation in seven parts on diasporic identity. The

second part, "Measure," obliquely recounts the Asian origins of paper and

moveable type as well as their gradual diffusion westward to Europe. The

declaration "A way is open(ed), a hole is made," precedes a word square:

The word-spacing here reflects the text's struggle to speak about one place and time--medieval Korea--using an unrelated and ill-suited language--modern English. The grid-like arrangement of words attempts a compromise by permitting a reader to move through them both left-to-right, top-to-bottom (English) and top-to-bottom, right-to-left (traditional Korean). One "turns back" and "makes a turn" after each line, whether that line is horizontal (English) or vertical (Korean). The price of this compromise is degraded syntax. The words refuse straightforward integration into logical statements. Kim suggests one of the frustrations of bilingualism: a speaker endeavors to "translate" one heritage and its attendant social conventions into phrases intelligible to people for whom those things register as "foreign," only then to discover the two languages brushing against and deforming each another, producing unexpected, hybrid results.[54]Introduce single horse turnback

Introduction ride alone

(Capital) (fight alone) make a turn (27)

- Today's postlinear poets do not pursue a unified program, nor do they seek to establish a new, shared formal vocabulary. They work with and against normative reading procedures in their efforts to explore the full range of language's visual, auditory, and conceptual possibilities. Their projects vary greatly. Howe's quietism is in dialogue with the ascetic transcendentalism of the 1950s and 60s New York artworld, whereas Kim's bilingualism belongs very much to the 1990s, a decade when U.S. poetry opened itself to experimental articulations of racial, ethnic, and gender identities.[55] By charting these disparate projects, however, we will gradually produce a topographical map of contemporary visual poetics. The fecundity of the artistry might be daunting, but the results will be correspondingly richer and wilder, unsettled and unsettling.

I. Introducing Word Squares

|

| Figure

1: Word Square. Susan Howe, The Liberties (204). |

|

| Figure

2: Word Square. Susan Howe, "Heliopathy" (42). |

|

| Figure

3: Word Square. Susan Howe, Secret History of the Dividing Line (122). |

|

| Figure 4: Necker Cube |

II. "All Things Double"

III. Howe's Installation Art

IV. The Appeal of Grids, Clouds, and the Sea

V. Language Is Aural and Visual

|

| Figure 5: Ian Hamilton Finlay, "Acrobats." |

|

| Figure

6: Ian Hamilton Finlay, Fisherman's Cross (Solt, Concrete Poetry 205). |

VI. Spacing-Out the Ocean-Page

VII. Word Squares and Postlinear Poetry

Department of English

University of Washington, Seattle

bmreed@u.washington.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2004 Brian Reed. READERS MAY USE

PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S.

COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED

INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

I would like to thank the Stanford Humanities Center and the University of Washington's Royalty Research Fund for making this article possible. I would also like to thank Terry Castle, Bob Fink, Kornelia Freitag, Albert Gelpi, Nicholas Jenkins, Marjorie Perloff, and Susan Schultz.

1. Although Susan Howe claims that the label Language Poet does not apply to her (see Interview with Keller 19-23) she nonetheless published in L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, the poetics journal from which the movement takes its name, as well as other Language-affiliated periodicals, such as O.blek, Sulfur, and Temblor. She has also consistently appeared in the anthologies that have defined the movement for outsiders, such as Ron Silliman's In the American Tree and Douglas Messerli's "Language" Poetries.

2. See Back 3-4 for summary comments on "Howe's visual experiments" as the "distinguishing mark" and "signature" of her style. See Dworkin for a provocative overview of the subject.

3. See Möckel-Rieke 291 for a rare discussion of Howe's "ballad" style.

4. See Dworkin for an extended analysis of the "static" and "noise" that Howe produces through her manipulation, superimposition, and violation of found texts.

5. See Back 142-44 for an analysis of the "violence" conveyed by the "radically disrupted and chaotic" pages in Eikon Basilke. For the remainder of this article, I will be using the following abbreviations for Susan Howe's long poems and works of criticism: ASFT for Articulation of Sound Forms in Time; BM for The Birth-mark; CG for Cabbage Gardens; CCS for Chanting at the Crystal Sea; DP for Defenestration of Prague; EB for A Bibliography of the King's Book, or, Eikon Basilike; Fed for Federalist 10; H for Heliopathy; HP for Hinge Picture; LTC for Leisure of the Theory Class; L for The Liberties; MED for My Emily Dickinson; MM for Melville's Marginalia; NCM for The Nonconformist's Memorial [the long poem, not the collection]; PS for Pythagorean Silence; R for Rückenfigur; SBTR for Scattering as a Behavior Toward Risk; SHDL for Secret History of the Dividing Line; and SWS for Silence Wager Stories.

6. For one possible exception, see the six-by-six word arrays in Robert Duncan's "The Fire: Passages Thirteen" (Selected Poems 82-87). Howe may know this poem. See Howe, "For Robert Duncan" and "The Difficulties Interview" 17-18.

7. See also e.g. ASFT 12, 14, 15; PS 78, 82-84; L 205-8, 216; and SHDL 89, 116.

8. This preface appears only in the 1990 reprint of ASFT that is on the List of Works Cited. It does not appear in the 1987 version of ASFT published by Awede Press.

9. See e.g. Back 42-44; Perloff, "Collision" 528-29; and Reinfeld 142. Compare McCorkle paragraphs 5-6, 13-16. For other efforts to close read Howe's word squares, see e.g. Back 21-22, 27, 96-100, and 118-19; Green 86-87 and 99-100; Keller 231-35; and McGann 102.

10. Compare Back 44 on the "multiple and generative landscape" of this word square.

11. Compare Selinger 367 on Howe's word-grids: "the raw material of a poem yet to be written or all that remains of a piece now decayed."

12. See Benjamin 150-51 and 153.

13. Swinburne has recently become an important presence in Howe's work. See "Frame Structures" (12) and "Ether Either" (122; 126-27). See esp. the 1999 long poem The Leisure of the Theory Class, which immediately precedes Rückenfigur in Howe's book Pierce-Arrow (passim).

14. Compare Back 46 ("tendency to contradict herself, every articulation containing itself and its opposite").

15. See Mitchell 45-56 for a discussion of "multistable" images such as the Duck-Rabbit.

16. The installation materials are stored in Box 15 of the Susan Howe Papers (MSS0201) at the Mandeville Special Collections Library of the University of California, San Diego. Hereafter I will be citing unpublished materials in the Susan Howe Papers as SHP, followed by their box and (if relevant) folder numbers. For Long Away Lightly, see SHP Box 15, Folder 1. For On the Highest Hill, see Folder 4. For Wind Shift / Frost Smoke see Folder 8. Unfortunately, no dates are provided for individual pieces, and the various materials are unlabeled, rendering many of them mysterious or unidentifiable. Several of the scraps of poetry used in the installation pieces, such as that beginning "on the highest hill of the heart," also appear in SHP Box 6, Folder 6, with Howe's earliest poems. In fact, there one can find "Wall 1" and "Wall 2," poem sequences that either derive entirely from the installation work or represent the installations' poetic precursors.

17. See esp. SHP Box 15, Folders 2-3 for some of Howe's meticulous installation instructions.

18. See SHP Box 15, Folder 5 for this photograph.

19. See SHP Box 12 for the working notebook dated 26 April-15 July 1974, in which she declares herself Smithson's lineal heir.

20. See SHP Box 15, Folder 4.

21. For Smithson's Ginsberg imitations, see Smithson 315-19.

22. Reinhardt's "Black Paintings" are notoriously difficult to reproduce. For an example, go to the Guggenheim Museum's online collection <http://www.guggenheimcollection.org>, search for "Ad Reinhardt," and enlarge the available image.

23. For samples of Martin's and Ryman's work, visit the Guggenheim online collections collection at <http://www.guggenheimcollection.org> and search on the artist's name. For Martin, see also the online galleries available from the Los Angeles County Museum <http://moca-la.org> and the National Museum of Women in the Arts at <http://www.nmwa.org>.

24. See e.g. DP 89; EB 61-62; L 162, 180; LTC 32; MM 103; NCM 20-21; PS 77; SBTR 70; SHDL 94, 113, and 114.

25. The Awede Press edition of ASFT is unpaginated. When Wesleyan University Press reprinted ASFT, they crammed these two lines into a single page with another lyric (11).

26. For Krauss's influential account of minimalism, see Passages in Modern Sculpture 198-99, 236-42, and esp. 243-88.

27. In a 1993 interview, Agnes Martin declares herself an abstract expressionist (15) in the "transcendental" mode of Rothko and Newman (13). She says that she has always sympathized with minimalism's aspiration toward perfection, but intuition and inspiration are necessary to lead one beyond mere mechanical perfection to its "transcendental" corollary (Interview with Sander 13-15).

28. I concede that Reinhardt was an advocate of art in its purity and that he considered any confusion between art and religion to be anathema. Nonetheless, as Krauss points out, "the motif that inescapably emerges" as one contemplates his black paintings "is the Greek cross" (Originality 10). For Howe's transcendentalist reading of Reinhardt, see "The End of Art" 3-4.

29. Agnes Martin's paintings reproduce very poorly in digital formats, but for a hint at the dynamic Krauss describes, see the interactive "tour" of the Agnes Martin Gallery available on the web page of the Harwood Museum (Taos, New Mexico): <http://harwoodmuseum.org/gallery4.php>, last accessed 29 January 2003.

30. See the Keller interview for Howe's cursory recollection of this correspondence (20). For Finlay's letters to Howe, see SHP Box 1, Folders 4-6.

31. See Bann 55-57. See also Stewart 124, 129-30, and 139.n34. Stewart posits that around 1971 Finlay's relation to the sea shifted, and that fishing boats gave way to warships in his work (124-25).

31. The original is unpaginated. See esp. the second, third, fifth, sixth, and eighth openings. I have included in the List of Works Cited a recent, readily available translation of Un Coup de dés that respects Mallarmé's original layout.

33. See Palatella 74-76 for more analysis of Howe's commentary on Fisherman's Cross.

34. See E. Joyce, paragraph seven for a comparison between Mallarmé's Un Coup de dés and Howe's compositional practice.

35. See for example: ASFT 1, 23, 25, 29, 35, 38; CCS 61, 63, 68; CG 79, 79, 80, 81, 85, 86; DP 88, 96, 100, 101, 103, 117, 124, 135, 146; EB 75, 79; H 43; HP 53, 54, 55; L 158, 164, 168, 172, 173, 174, 187, 196, 198, 199, 213; MM 123, 134, 145, 146, 150; NCM 17, 19, 26, 33; PS 28, 30, 31, 42, 45, 48, 51, 53, 56, 60, 64, 80; R 131, 136; SBTR 66; SHDL 90, 105, 110, 111; and SWS 36, 42.

36. See for example BM 17, 18, 26, 28, 32, 37, 46, 50, 55, 61, 69, 82, 83, 132, 150, 166, 178; "Ether Either" 119, 123; "For Robert Duncan" 54, 55, 57; MED 45, 87, 106, 109; "Since a Dialogue" 172; "Sorting" 297, 308, 311, 319, 320, 326-327, 323, 325, 328, 338, 342; "Where" 4, 11, 12, 18, 19; and "Women" 63, 88.

37. Howe spent her childhood and youth split between the United States and Ireland. See "Ether Either" 112-13 and 118-19. See also a letter by Howe qtd. in Möckel-Rieke 303.n92. And see BM 166 and "Sorting" 320. Ireland in Howe's work is identified strongly with the ocean and ocean-crossing--see HP 54, L 213, "Sorting" 338 and the first page of WB. For Howe's discussion of her husband's love for the ocean and ship-design, see "Sorting" 295-97 and the Keller interview 4-5 and 29.