Maximal Minimalism

Charles AltieriUniversity of California, Berkeley

altieri@uclink4.berkeley.edu

Rei Terada

University of California, Irvine

terada@uci.edu

© 2005 Charles Altieri and Rei Terada.

All rights reserved.

Review of:

Robert Smithson. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. 12 Sep.-13 Dec. 2005.

We saw this show together. We saw it differently. We enjoyed those differences and wanted to convey that pleasure. Below we mention Smithson's Four-Sided Vortex, which gives the viewer the ability to see one's companions in a mirror instead of oneself, for a moment. Here are some glimpses of our experience.

Boy Genius

MOCA's approach to the problem of exhibiting Robert Smithson de-emphasizes writings, plans, and reproductions of large-scale works (although these are represented, selectively) in favor of Smithson's paintings and drawings, a few films, and several elegant and quietly assertive sculptures. Through this relatively intimate Smithson--a living room and backyard kind of Smithson--the viewer remembers and catches glimpses of the colossal earthworks. The effect is to imply a continuity between the kind of interest we have as children in the rocks and old lumber that collect at the side of one's house and the architect's ambition to reshape the landscape, or between junior high school notebook fantasies and Smithson's brainy, eclectic sketches for projects (for example, his Proposal for a Monument in Antarctica [1966]). In the showily juvenile male fantasies of the barely post-adolescent Smithson, airplane parts and erect nipples are motifs of competing interest; the famous Smithson too was never more than a very young man, his language full of ostentatious allusion, deadpan humor, and other tropes of precocity. The question is not so much how Smithson's smart-aleck rhetoric becomes something more as how he manages to convey the nascent challenge in adolescent intellectualism when it starts asking questions of the physical world.

Beginnings

Robert Smithson seems an enticing anomaly. In an age where the reigning interest is political, Smithson still gets treated as he would want to see himself--that is, through the lens of powers attributed to genius or, as he puts it, as above all a "generative artist" (88), creating context more than responding to specific cultural forces. Thus MOCA's show brings into focus Smithson's capacity to reinvent himself in order to make art objects so visibly and entertainingly the realization of a thinking that could have no other satisfying outlet. Make no mistake: Smithson was so deeply engaged in the cultural life of his time that he could become perhaps his age's most powerful critic of the then-dominant formalist modernism. But he could manage that role because his fealties lay not with the human or social orders so much as with an imaginative site produced by the mind's dialogue with geologic time and crystallographic space. Comparisons to Leonardo are not uncommon, and not unjustified in relation to Smithson's constant inventive activity, as well as in relation to how that activity seems to warrant a position apart from the culture wars.

Born in 1938, Smithson worked at first (after high school and the army) primarily in drawing and in painting. His brushwork and palette in works like Eye of Blood (1960), From the Valley of the Suicides (1962), and various renderings of the passion of Christ make me think of Philip Guston on speed. There is everywhere the intense painterly activity unwilling to settle for representation, but like Guston, Smithson insists on providing an image as the provocative source of that activity. But this Guston-on-speed also manifests a Blakean spirit of linear excess, here adapted to what would become the cross between the psychedelic and the comic book sensibilities common in the art of the mid-seventies. In one respect Smithson's painting is the work of the classic repressed nerd (fifteen years before the emergence of that figure for genius), albeit one talented nerd. I love the tension between human and organic forms in the painting and drawings responding to Dante's valley of the suicides: clearly suicide is no solution, since the soul's discomfort only carries over into other forms of alienated material existence. The Christ paintings are remarkable for their evocation of a manifestly staged pathos that elicits what can only be called "vulnerability on a divine scale." Even Christ, or especially Christ, finds it impossible to inhabit an expressive body and must resign himself to metonymies like hands and feet. When the entire body emerges in Jesus Mocked (1961), it seems so aware of its impotence relative to what it might want to signify that it is ready for the tomb.

Thought as Non-Site

Like Warhol, whose early works include little portraits of people covered in gold leaf, miniature versions of his paralyzed icons of fame, Smithson explores anxiety about and attraction to reification as the other side of familiarity with inanimate nature. By this logic he moves from comic-like representations of cultural stereotypes to paintings based on Dante and Blake--allegories of imprisoned persons whose fantasies of escape into mind produce only a more rigid version of the body, or "emanations" that seek to represent something that is neither body nor mind, but wind up seeming less than both. Meanwhile, on the separate track of the sketches for sculptures and architecture, Smithson's persona unfurls, like an emanation itself, in the handwritten annotations that populate these pages. The notes seem to immerse the sketches in a mental non-space of arcana and asides. Like the voiceover Smithson uses in a film or two, these jottings have a thin, haphazard relation to the shapes on the page, but present the artist's thinking self as an ironic, disembodied interlocutor.

The Unrepresentable and the Presentable

I think of Cézanne as the presiding model of visual genius here. Cézanne had similar beginnings. He did not know Blake or prefigure the alienations of psychedelic culture, but his early work shares with Smithson's the sense that the only good image is an image so distorted by the painter's energies that these energies have to seem utterly overdetermined in relation to what they are trying to represent. The representable is haunted by the unrepresentable, with the painter's affective identity established by the effort to locate the sense of difference between the two as an effect of the ego.

Then both artists eventually sublate the energies that undo representation into the will to form enabling the precision of gestures toward representation. (I am counting the Nonsites as bizarre representations by representative materials.) Both realize that identifying the individual subject only with the production of excess with energies possible for the eye is less a result than a cause of alienation. Ultimately the work of genius is not to express the self's anxieties but to find sites where anxiety seems trivial in comparison to the mind's capacities for intricate impersonal appreciation of where it can find itself situated. One does not have to look very hard at Smithson's Eye of Blood to see how it could be transformed into a stone spiral jetty in a red sea, in a world where the return of energy to the subject is a sign of insufficient awareness of the contemporary person's limited place in the world.

Blind Spots and Rabbit Holes

At least two kinds of Smithson's mirror works are represented at MOCA: wall-mounted or floor-standing arrangements of brightly painted metal with reflecting panes, and heaps of rocks and minerals bisected by glass. The first group are funhouse-like pieces with pop/op touches. Smithson frames blind spots as though once you knew where one was, you could handily store things in it. Thus the sculptures model and parody psychic interiors. Untitled painted metal and glass polyhedrons (1964-65), like large split and mounted beveled stones, make the floor hover over one's head and parts of the room at middle height disappear. A reconstruction of Smithson's Enantiomorphic Chambers--a series of metal and glass frames resembling a row of partly opened residential windows--evokes infinite regress when you try to look through all the frames from one end. The floor-standing sculptures look more unassuming and are more deceptive. Four-Sided Vortex (1965), a mirror-lined steel rectangle about three feet high, is a kind of negative wishing well: looking in, you can stand in such a way as not to see yourself, only the person beside you. A similar untitled piece from 1965 looks like the kind of green plastic wastebasket you might come across in a city park, but drops the eye into a kaleidoscopic netherworld.

Minimalism Maximized

Smithson put himself on a path to this capacious perspective by turning from painting to collage, then to wall structures that drew their inspiration from crystallography, then to a geological perspective that could contextualize why the crystalline might prove so fertile a source of fascination. To grapple with the content promised by these different angles of vision, Smithson turned from expressivist traditions to the minimalism that had recently become fashionable. But he could accept neither the cult of all-at-once apprehension that attracted Donald Judd and Frank Stella nor the pure play on conditions of response that characterized work like Robert Morris's circles. Technically his work in floor sculpture would be characterized not by minimalist seriality but by progression in various dimensions (22). And, more important, that work would not settle as either a distinctive, immediately graspable object or an event manifesting some aspect of the phenomenology of seeing. Rather, object and event would enter dizzying interactions allowing both object properties and event properties to dangle intricate metaphoric possibilities leading beyond the material object but not beyond theater (in the sense of the term popularized by Michael Fried). In Smithson's later work, all the event properties that include the viewer's perspective return us to aspects of his materials while opening them up to the play of mind. Even his simplest structures, like Pointless Vanishing Point (1967) and Leaning Strata (1968), make manifest forces that enter perception while focusing one's attention on astonishingly elegant objects that one has to let unfold and linger before the mind's eye.My general claims about Smithson's relation to minimalism will be difficult to demonstrate in this limited space. I hope it suffices to say that a good part of the breakthrough stems from his appreciating the capacities of mirrors to provide both distinctive substance and irreducible metaphors of reflection and mobility. By making the mirrors part of floor sculptures, Smithson can extend the sense of enantiomorphic structure into complex interactive fields. As one walks around the sculptural object, the mirrors simultaneously stabilize the assemblies of rock by making them dynamically occupy space and destablize those assemblies by playing on what is substance, what shadow, and what illusion. For example, in Chalk Mirror Displacement (1969) (see Figure 1), eight long but low rectangular mirrors radiate out from a center, dividing the work into an open octagon. Because the space is filled with crumbled mineral chalk of various sizes, one is tempted to think of this piece as a large pill box for minerals. But the minerals will not rest in their container. We are constantly stopped as we move around because the glass seems both transparent and reflecting. So the pile of chalk seems both continuous and discontinuous: at times the chalk appears as fluid as water, even as we see the edges and shadows that mark discrete objects. Yet these discrete objects also enter into various mirroring relations, so what is substantial merges with what is reflected. And the chalk comes to seem endlessly alive, proliferating textural qualities and rewarding the sense that as one moves one is productively bound to sheer contingency. How one sees and how one thinks depends here entirely on where one stands.

Figure 1: Chalk Mirror Displacement (1969)

Estate of Robert Smithson

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York

© Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York

Lyric Sheets

Smithson's mirror-divided piles of rocks and minerals are the really lyrical pieces in the exhibition. The mirrors lie on the floor with the minerals on top of them (as in his Nonsite from 1969), line a corner so as to seem to round out an actually interrupted cone (as in Mirror with Crushed Shells [Sanibel Island] [1969]--see Figure 2), or bisect minerals sloped into symmetrical heaps so that as the viewer looks at any segment of the pile, the reflection of the segment seems to join it to the whole, even though our actual view of the whole is occluded by the slicing glass. In each case the reflections act as supplements so nearly perfect that we continually overlook what's missing and what's been quietly replaced. This is "aesthetic ideology" so smooth that you can barely feel its sublimated violence. The piles of stones themselves imply human contact, since they're beautified by sorting. Loose aggregations rather than objects, they are not integral enough in the first place to be broken by the more explicitly human interruptions of the dividing glass sheets. As a result there is something simultaneously sacrificial and nonviolent about these pieces. The glass planks that section them are as simple and surgical as the monolith in Kubrick's 2001, yet painless, as though phantom limbs really restored amputations and any cut were also a repair.

Figure 2: Mirror with Crushed Shells [Sanibel Island] (1969)

Estate of Robert Smithson

Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York

© Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York

Nonsites and the Play of Difference

In Rocks and Mirror Square II (1969/1971) (see Figure 3), Smithson turns the dividing panes of mirror into a rectangular container and rocks take the place of the chalk, now located both within the mirror and outside as a border. Here relations between what is inside and what is outside seem as unstable as the dizzying interactions between substance and reflection and between determinateness of structure and the flow of constant visual eventfulness. Because we are invited to move around, we cannot help thinking that the psyche is caught within this same play of inner and outer, self-reflection and escape from self into elegant sheer materiality. At the same time, the rocks convey an aura of immense power to resist inwardness because they retain their obdurateness even as they seduce us with texture and intricate play among edges and shadows. Ultimately it seems impossible not to feel at once deeply grounded in geological time and as inconstant as passing reflections. And both worlds of flux and permanence seem to mock our merely human interests. One might say that Smithson's genius was most evident in his realizing in practical terms how almost a century of abstraction in art might produce this turn from the anthropomorphic in life.

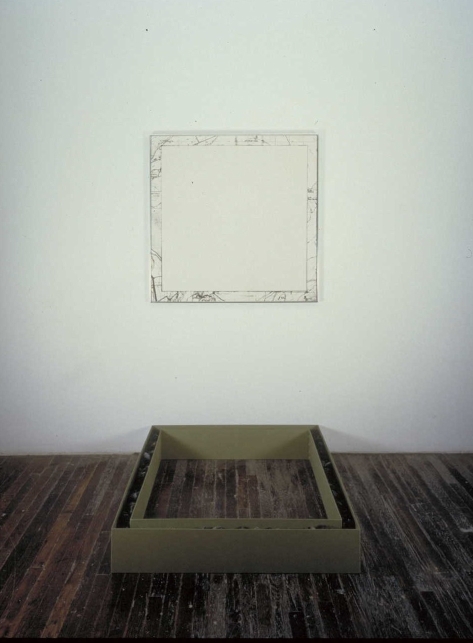

I am going to have to pass over Smithson's many intriguing sketches and diagrams, the remarkably inventive photo sequences that place mirror surfaces in various landscapes, and Smithson's fascination with what might be called marginal architectural forms that begins with his work on the Dallas Airport. But I have to at least mention my favorite Nonsite, Mono Lake Nonsite [1968] (see Figure 4). This combination of wall and floor objects offers an apparent wall map of the lake with most of its surface covered by a plain white painted rectangle. Then the floor piece provides one rectangle nested within another, the larger one matching in size the white painted area. The rectangles present the stuff that the map refers to but which cannot be represented by the map--the outer rectangle containing rocks and the inner one sand. Likewise, I must remark on two films, the justly famous thirty-two-minute film of the building of Spiral Jetty and a film of Smithson describing a suite of architectural photographs he made at the Hotel Palenque in which his speaking tone proves as intricate as the relation between inside and outside in his work with mirrors.

Figure 3: Rocks and Mirror Square II (1969/1971)

Image used by permission of the National Gallery of Australia

Art © Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Figure 4: Mono Lake Nonsite (1968)

Image used by permission of the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego

Minimalist Architecture

The domestic cousins of Smithson's negative places--unrealized plans, blind spots, margins, minds--are airports, outbuildings and hotels, the between- and afterthoughts of supposed destinations. The exhibition gives us Smithson's recorded comments over a slideshow of photos he took at the Hotel Palenque, a dilapidated Yucatan inn of no more vernacular fascination than any neighborhood dive, where you might imagine someone like William Burroughs staging a literary decline. In a laconic vein somewhere between Cage and Godard, Smithson praises or pretends to praise to an amused university audience the idiosyncrasy that accumulates there or anywhere. A set of double doors painted green, turtles in the turtle pond, "interesting" rubble--minimalism's respect for the indestructibility of curiosity, or irony about that respect?

Memorials

The otherwise admirable catalogue does not pay much attention to questions of tone, or, for that matter, to the expressive detail of his work. It is too busy trying to figure out what Smithson might be thinking--perhaps one of the pitfalls of being taken as a genius. The most useful of the essays for me were Eugenie Tsai's summary of Smithson's career, a wide-ranging interview focused on his dislike of Duchamp, and particular treatments of his relation to Christianity, of his idea of the enantiomorph, of his work in the Yucatan with mirrors, and of his legacy in the form of "post-studio art."

Futures

In the brief film Swamp (1969), Smithson urges his collaborator, Nancy Holt, to walk with her movie camera into a marsh thick with rushes and reeds higher than her head. Smithson directs her to go left or right or turn around and walk further, seemingly randomly, in this landscape without reference points. Anxious almost immediately, Holt keeps saying, "I can't see anything!" Smithson tells her it's OK, she should just keep walking, straight ahead as much as possible. It's a surprisingly tense encounter, the little contest between her body and the rushes that give way easily underfoot, but never give onto anything else. She never becomes less anxious and never learns anything about where she is. In the middle of a discussion about how much film is left (Smithson thinks there should be more), the film runs out. We might read Swamp as a mini-emblem of the antiheroism of Smithson's contacts with the nonhuman, contacts that record resistance to the latent inanimacy of the living body without making too much or too little out of it.

Robert Smithson closed at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles on December 13. The show travels to The Dallas Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. The catalogue for this exhibit is Robert Smithson, ed. Eugenie Tsai (Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California P, 2004).

Department of English

University of California, Berkeley

altieri@uclink4.berkeley.edu

Departments of English and Comparative Literature

University of California, Irvine

terada@uci.edu

Talk Back

-

COPYRIGHT (c) 2005 by Charles Altieri and Rei Terada.

READERS MAY USE PORTIONS

OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT

LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE. FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO PROJECT MUSE, THE ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.