Enduring Proximity: The Figure of the Neighbor in Suburban America

Dana CuffUniversity of California, Los Angeles

dcuff@ucla.edu

© 2005 Dana Cuff.

All rights reserved.

- The figure of the neighbor in contemporary culture is both spatial and social: neighbors begin as strangers necessarily inhabiting proximate space. When that closeness is intense in duration, distance, and circumstance, it gives rise to potent, if not perverse, reactions. An estate owner's three-story fence that imprisons and intimidates his neighbor (see Figure 1) is surely spiteful, but neighbors can be far crueler, as we know from the history of the battle to integrate U.S. neighborhood schools since the mid-twentieth century, or even the genocide waged against proximate others in Germany or Rwanda. Intensified by proximity, the presence of difference--inescapable otherness--may press cultural norms past tolerable boundaries.

- Of course, neighbors are not usually spiteful. The notion of neighborliness often connotes the benign, minor kindnesses bestowed among co-residents that punctuate a steady state of general disregard. But when irritations arise, they can mushroom into disputes that do not seem warranted on the surface. Neighbors wage battles with and against neighbors to defend unpretentious terrains that would appear insignificant. So perhaps neighborliness should be construed as a set of concerted practices by individuals in a relationship somewhere between friendship and enmity. The rhetoric of the neighbor condones interaction without intimacy or intensity; we especially resist vehement interchange for fear of antagonizing those among whom we must live. It is this repressed desire for something more or less than neighborliness that erupts in bizarre local disputes, often directed just outside the neighborhood.

- The main reason neighbor relations are charged is sheer proximity. Unlike other social relations, including friendship, enmity, love, and even familial relation, space is inherent to neighborship. Unlike the "neighbor" at the office or the one seated beside us at a concert, residential neighbors live their daily lives near one another over extended periods of time. This remains true even in an era of increasing household mobility. Further, residential neighbors are in a significant and often causal relation. Their actions impinge upon one another, and at some levels, are mutually dependent: neighbors affect each other's property values and make their street a safer or more dangerous place. We may like, dislike, or hate our neighbors, but we are locked in relation with them to some degree.

- In this essay I scrutinize the figure of the neighbor through the architecture and planning of the American residential landscape. Neighbor architecture--that is, the forms of neighborhoods and all that goes into shaping them--has received little consideration in the study of architecture, as has the construct of the neighbor itself. Psychic and cultural negotiations concerning the latter are made visible to some extent in critical discussions of literal negotiations over neighborhoods; when neighbors debate a proposed affordable housing complex, for example, their arguments about traffic, parking, and density are understood to reflect fears of difference. But there has been little critical reflection on established physical forms for neighborhood, in contrast to architectural styles for individual buildings or urban planning strategies for larger regions. The open-endedness of possible neighbor architectures, I suggest, produces a new way of looking at residential architecture itself.

- Just as neighbor relations are unlike other intersubjective relationships, neighborhoods are unique physical environments. Unlike districts, towns, or regions, neighborhoods embody a social relation linked to specific land use. A neighborhood is comprised of people living in close proximity in significant relationships, yet they are usually there by default. Further, the figure of the neighbor involves not only the space between strangers, but the relation of the house as a non-human object to its human occupants and the relationship between interiority and exteriority modeled therein. Bachelard writes in The Poetics of Space that "it is not enough to consider the house as an 'object' on which we can make our judgments and daydreams react. . . . the phenomenologist makes the effort needed to seize upon the germ of the essential, sure, immediate well-being it encloses" (3-4). Bachelard's idealized imagery places the experience and memory of the self inside the house, from cellar to attic. The interiority of the individual and the house in turn both reside within an exterior public presentation. The house is figured not as an inanimate solid object, like a rock, but like the well-worn boots in Van Gogh's painting, read so eloquently by Jameson. The house is a receptacle for humanness and a record of its existence. But the same can be said for the neighborhood as a whole, which has its own interiority. The figure of the neighbor reverberates in my reading of myself and of my neighbor in his house and in our neighborhood.

- What happens in the neighborhood when the villager's workboots give way to Warhol's "Diamond Dust" stilettos; when the generational family home yields to mass-produced Levittown? The "flatness or depthlessness" and "new kind of superficiality" that Jameson attributes to postmodernism is indeed present in an endless string of similar commodified houses. The postwar suburb homogenizes a group of strangers through exterior repetition and erodes presumptions of interiority. Yet the repetitive plans of mass-produced houses also attempt to provide some reassurance as to the identity of the inhabitants. Behind the front door, inside the picture window, is a place known to each neighbor as her own. In the mass-produced house we can imagine both our own uniqueness and our neighbor's familiarity. Decorating the same basic shell furnishes each household with a limited degree of individuality. But in the mass-produced house, the neighbor's interiority is not fully explored; it remains both real to and somewhat distant from us. The postwar suburb corresponds to the territory between workboots and high heels, between the fully situated biographical individual and the interchangeable, depthless stranger. The mass-produced box house reproduces an arm's length familiarity among neighbors.

- The figure of the neighbor as I am defining it here is an up-close construction of human otherness. Thus neighbor relations are proto-political, growing from imposed, inescapable, and open-ended confrontation between self and other. Sociality located beyond the household and before the city forms a grain of sand around which participatory democracy or civil society can begin to take shape. And if the neighbor can be associated with the political conceptually, it is also incumbent upon us to reckon with the concept empirically: neighborhoods are among the most forceful political entities in the U.S. today.

- The potency of neighborhood politics has led some observers to conclude that the future of national politics is not to be found in the bleak "vanishing voter" syndrome, but in community associations. The energy that propels neighborhood activism is indeed an abundant resource: the proximate differences encountered by residents can become the substrate of collective practices, from processes for deciding how deviance on the neighborhood street will be handled to more formal local planning decisions. According to this optimistic view of community associations, civil society begins in the neighborhood; neighbors trying to stop gang activity in a nearby alley may then try to keep their library open via a citywide tax referendum. A civics founded on such actions would by definition encompass opposing views, which would have their own legitimate forums (city council hearings, neighborhood watch meetings). Neighborhood civics has its shadow side, however, in not-in-my-backyard activism that shunts unwanted and uncertain change somewhere else. Local interests exceeding the scope and scale of individual households are often defined through the us-versus-them distinctions inherent to gated developments. Over half of all new urban housing now takes the form of "private communities" in which all the terrain is locally owned--streets, parks, parking, everything.[2] Like Charles Eames's film Powers of Ten, which figures exponential growth through the camera's dramatic leaps back from the object, private communities step away from the household to construct the next degree of otherness outside the neighborhood gates.

- There is a paradox here: cohesive community politics also seem to weaken the ethics of neighborhood. At present the notion of community conjures a romantic, if not naïve, utopianism even as local planning boards are inundated with citizens protesting even the most minor local transformations. There are relatively few established cultural norms for neighbor relations and set patterns of interaction in neighborhoods (as opposed to the workplace or the family), yet such norms are beginning to take shape in the U.S. The American neighborhood is casting its political form through its physical environment and through battles over it.

- In his introduction to an edited collection subtitled The Politics of Propinquity, Michael Sorkin argues that free civil society is located in the city because of its intensity and its spaces of circulation and exchange. This repeats the argument famously made by Jane Jacobs some forty years earlier, with a slight but significant shift in emphasis. Sorkin decries the would-be universalism of the public sphere, advocating instead friction, multiplicity, and difference. In a way, he is advocating the recognition of the shadow figure of the neighbor--the realistic, frictive neighbor--as essential to the political function of the public sphere. Both Jacobs and Sorkin advocate dense urbanism, however. It would seem that they crave the vital intensity of the city. While it is true that, historically, urban settings have indeed generated strong communities, it remains a limitation that neither Jacobs nor Sorkin cares to imagine the suburban space of the neighbor and hence of contemporary political action.[3] Although I, too, would argue that the next generation of neighborhoods will reside not beyond but within the city, I want to understand more clearly the recent evolution of the U.S. suburban landscape.

- The architecture and planning of postwar suburbs--seemingly a self-contradiction--in fact design a narrative of sociality for middle-class America. The suburb makers marketed themselves as "community builders," a role that deflected attention from their actual prioritizing of interiorized households closely if weakly linked to others nearby.[4] These developers built groups of houses that paid little heed to the prospect of neighboring; instead they focused on the individual dwelling taken as an independent entity. Their capitalist realism, operating for the convenience of the supplier, quickly became the currency of the consumer as well (see Schudson and Kelly).

- The assumptions built into the pattern of that currency are astonishingly simple. Among suburban households, the street serves as the primary collective icon. Efficient infrastructural organization gives access to equal-sized land parcels, yielding blocks of private houses facing one another and thus sparking obsessions with traffic and parking. The cul-de-sac, a distinct and popular form for the suburban street, implies a closed, small web of neighbors. As we jump down in scale from the relations between a collection of households to the relationship between adjacent abodes, we encounter an implicitly neglected neighbor inscribed in the ambivalent side-yard setbacks that separate one house from another, and a more self-conscious neighbor in the picture window through which, in glimpses, the other is revealed. The self is not only contained by the house but shielded by it from the proximate other.[5] The thin skin of the suburban house both confronts and defends against the figure of the neighbor, at the same time that it exposes a limited view of its own occupants. This dynamic is inadequately conceptualized by the binarism of publicity and privacy. The space just outside the suburban house is distinct from the public sphere (think Times Square or Santa Monica beach). Likewise, the space within the suburban house is unprivate in numerous ways: the unvarying reproduction of its interior plan, the windows puncturing the façade, and the public function of the living room, to name a few. Exteriority associated with publicity provides resident strangers with group identity, while interiority engages an intimate, regulating privacy. Thus domestic architecture's delicate task is to filter intimacy with strangers. Inevitably, that close-up intimacy forms intense relations of contact and avoidance, as when neighbors become complicit in overheard domestic violence or become enemies over a dispute about the fence separating them.

- If Arendt is right that the public sphere demands visibility, that reality requires our shared perception of a visible world, then the neighborhood is a kind of hyperreality in which enduring proximity can push us to share too much, so that we want to shield our eyes or plug our ears. The right and duty to the phenomenal world that Kant urges upon individuals is, by Arendt's logic, deflected in the case of the neighborhood from the individual's relation to nonhuman phenomenality to the realm of intersubjectivity.[6] A sure discomfort invoked by this shift sets at least some of the deeper terms tacitly guiding suburban development. The constant distance separating one house from another or the street from the house, for example, not only overtly addresses fire safety regulations but implicitly serves as a buffer against unwanted intimacy.

- How did the figure of the neighbor implied by suburban housing evolve in the postwar era? I suggest that while there was one primary model of postwar suburbia--the collection of isolated houses exemplified by Levittown--a secondary model existed beside it: the modern neighborhood exemplified by the Mar Vista Tract in Los Angeles, designed by architect Gregory Ain. Of these two models, only Levittown has been reproduced, sometimes in easy replication, in other cases in perverse mutation. My comparison between Levittown and Mar Vista will be followed by two examples in which designers explicitly sought to have impact on the articulation of neighbor relations. Each case ultimately harks back to Levittown--to an extreme at Sagaponac on Long Island, New York, and as its figurative mythical twin at Celebration, Florida.[7]

- The ur-suburb Levittown sets the benchmark against which subsequent experiments in mass-produced, middle-class housing have been measured. It is generally argued that Levittown reflected the "American dream," not just of home ownership but of domestic life itself, yet it is more accurate to state instead that it constructed that dream. This sleight of hand persists in representations of suburban sprawl as the inevitable result of popular desire. If we examine but one angle of that phenomenon--the way a suburban neighbor is variably figured--we will also see how a taste for the suburbs was formed and how local politics evolved there.

- In the late 1930s and early 1940s, American architects, planners, and politicians projected a forward-looking society that would emerge after the war, living in houses in neighborhoods that likewise abandoned the past. Creative fantasies were primarily limited to the individual house, individual investment, to the self and the privacy especially coveted during the Depression and World War II, when deprivation, working, housing, and fighting were insistently, if not oppressively, collectivized. Architecture magazines conjectured numerous private homes of the future, but ultimately these differed little from the cost-efficient houses merchant builders dropped on subdivided farmland to accommodate veterans returning from the war.

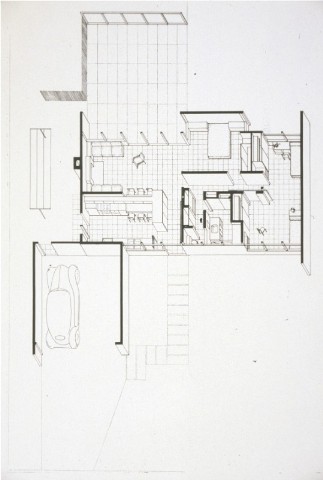

- At Levittown, thousands of identical, four-room "Cape Cods" were built to standards laid down by numerous local and federal agencies (see Figure 2).[8] These houses matched their prospective occupants' most urgent need: to escape overcrowded shared apartments. Rather than fulfilling residents' deep desires (as presumed by the rationale that popular taste guided suburban development), these houses met the needs of the builders. In Levitt and Sons's efficient house plan, not a single square foot is without explicit assigned function, as would be the case in an entry hall or even corridor (see Figure 3). The only ambiguous space is a stairway leading up to the unfinished attic, projecting a future in the oneiric sense and in terms of real estate speculation. Possibility soon depended on a do-it-yourself way of life. To help homeowners realize that possibility, local publications offered advice about how best to expand, decorate, and remodel--that is, to individuate ever-so-slightly over 17,000 homes that came in just two basic models.

- In John O'Hagan's 1997 documentary film Wonderland, early residents--each portrayed as an everyman of Levittown--describe Levittown's Blue Velvet side. Apocryphal stories, often repeated, feature self-similar houses that looked so much alike that husbands went home to the wrong wives. A woman recounts her experience of being haunted by a ghost whose greatest audacities are removing the lining from her jacket and nicking a corner of her coffee table. The interiority of the neighbor is figured to be as bland as the public appearance of the house on the street with which one was already familiar. Private interiors, it turns out, are imagined to be as knowable as the Bendix washer or TV built into every residence.[9] At the same time, the reassuring, banal minimalism of Levittown is cast as a mask of superficial sameness that veils an underbelly where wife-swapping, racism, alcoholism, eager consumerism, and general malaise were housed alongside the mythos of the model American family.

- The figure of the neighbor in the original Levittown exists mainly in absentia. The interstitial space between houses is ambiguous at best, front yards are deep and relatively uninhabited, porches are non-existent (see Figure 4). Except in the last Ranch model home built in 1949, the small puncture in the façade was hardly large enough to be called a picture window, and served as the only frontal link between inside and out, mediating family and neighborhood.[10] This is not to say that Levitt and Sons and the Federal Housing Administration had no conception of the neighbor. The influx of so many residents just home from war, starting families and struggling financially, made the Levitts fear their development would deteriorate into a new kind of slum unless they instituted measures of control. A variety of means were used to define the neighbor through authoritarian control, pressure to conform, and the insistence on privacy through absence of physical expression. The Levitts insisted, for example, that lawns be mowed; when they were not, a crew performed the task and billed it to the resident. Later a homeowners' "community appearance committee" continued the practice. The Levitts also ruled that drying laundry be moved inside on weekends. The laundry line, symbol of the intimate proximity of lower-class urbanites, was shunned or interiorized in Levittown, at least on its most public days. A newsletter explained that "hanging wash on Sunday might annoy neighbors, who are probably entertaining friends or relatives. Why not save it for Monday or hang it in the attic?"[11] To accommodate this rule women did dry their laundry in the attic or even in the living room. Levittown's public face--at least when the neighborhood was inhabited by men home from work and by guests--required active disidentification with the visible intimacy of neighbors.

- The problems associated with slums and potentially with Levittown were pathologized in the logic of Levitt: they could infect and spread to others. This necessitated a further measure: fences were not permitted. All residents had visual access to their neighbors' back and front yards. This democratized the Panopticon's principle of surveillance: at Levittown, everyone could openly police everyone else. With no mediation between interior and exterior, residents' secrets, their hidden selves, had to be contained in four small rooms. In public, social conformity dominated the relationship between houses through regulations and residents' practices. Nonconformity was an affront that bordered on subversion and potentially destabilized the emerging community (see Kelly 62). Levitt and Sons's project to establish stability was taken on in earnest by the Levittowners.

- As for the neighbor as a proto-political figure, Levittowners were not "bowling alone."[12] Amid the ocean of individual houses, neighborhood centers contained schools, community stores, and parks, and residents started innumerable local clubs and branches of national voluntary organizations. Presumed degrees of homogeneity were discredited in these voluntary organizations; as members discovered their differences, factions, conflict, and debate were the norm. Groups tended to splinter along class lines, so that group survival depended upon leaders who could generate cooperation and tolerance.[13] Political action as a form of resistance was marked in the early days of Levittown, but the Levitts were quick to shut down opposition.[14]

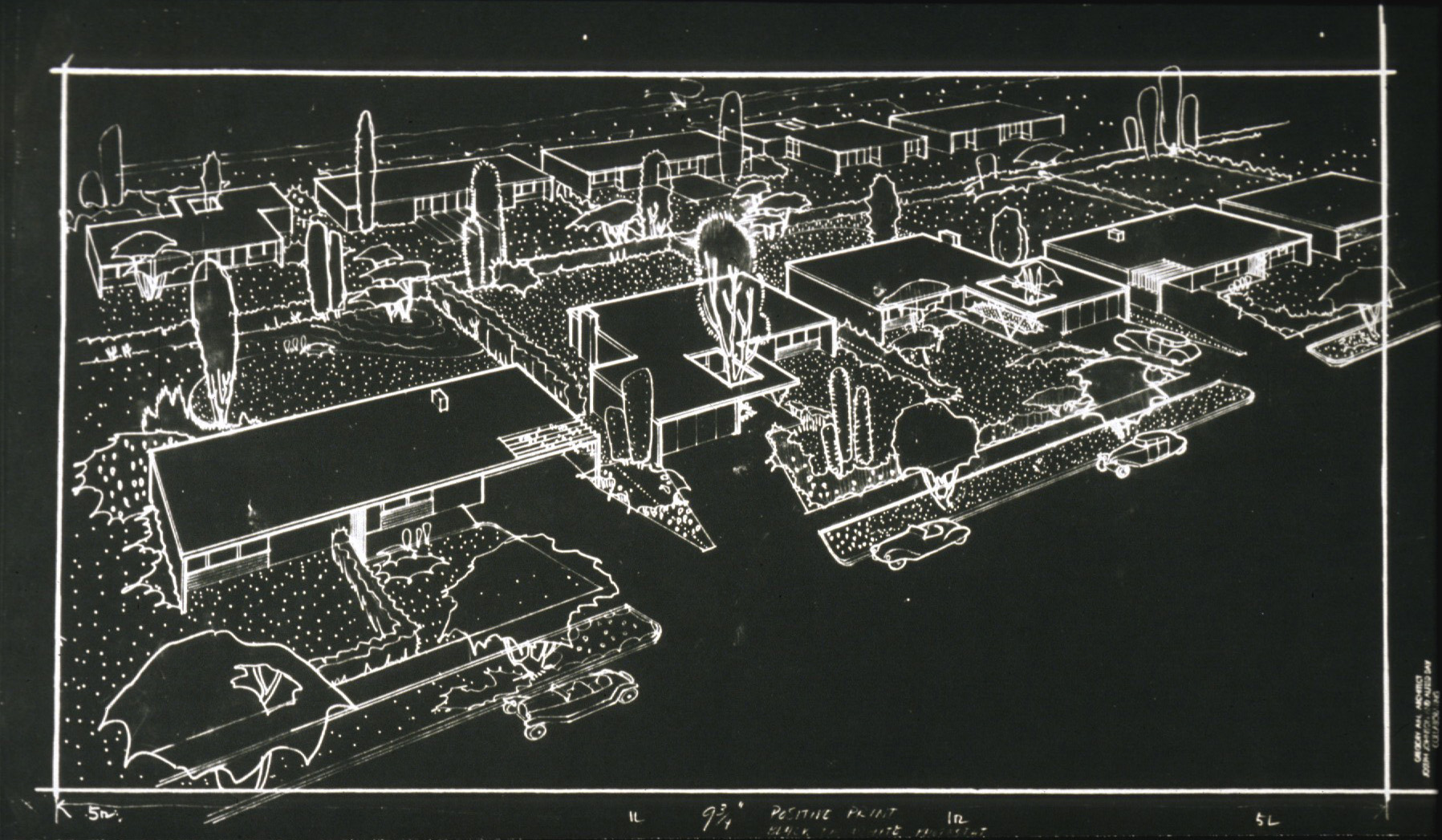

- At another tract of postwar middle-class houses, a progressive neighbor was figured not only in the street and front yards but inside the houses. Architect Gregory Ain's Mar Vista Tract in Los Angeles (1947) is one of a handful of modernist experiments across the United States that offers a striking contrast to Levittown.[15] Like the latter, Mar Vista is a study in mass housing for the middle class, though much smaller: just over fifty houses were built on three parallel streets. The small scale of production created a district within a town rather than a region de novo. Instead of standard long and narrow lots, Ain created short and wide lots, each with about eighty feet of street frontage. Landscaping by the distinguished modernist Garrett Eckbo unified the exterior through tree-lined streets and uninterrupted parkways. At the rear of the houses, fences separate private yards, but the landscape simultaneously treated those spaces as a continuous whole (see Figure 5). Houses together with vegetation create a formally explicit double reading of the individual and the collective, of privacy and public identity, that distinguishes the Mar Vista Tract.

- The occupants of this modernist suburb moved for many of the same reasons as did their Levittown counterparts.[16] Yet the figure of the modern neighbor was as distinct from Levittown's as were the modern house and neighborhood itself. Rather than relying on social controls like the rules the Levitts laid down in Levittown, Mar Vista's repetitive house form provides an expanded realm to the private individual while leaving the imagination of the neighbor open and unscripted. In contrast to the social conformity that dominated Levittown, this willingness not to figure the neighbor, I suggest, is a stronger indication of the capacity for tolerance and actual association than Levittown's nervous implication that the neighbor must be a lot like oneself.

- Instead of a reassuring veil of sameness, the Mar Vista Tract creates its neighborhood from an unpretentious abstract form. Minimalist rather than stripped-down, economy serves an aesthetic purpose in Ain's design. The street becomes a parkway, a shared field both defined and occupied by walled compounds. Together the self-similar objects create not a scattered array as at Levittown, but a unified wall along the street that links the diverse progressives who chose to live there. No friendly neighbor is figured in these façades, where the filtering function is architecturally explicit: the street-side exterior belongs to the collective, formal and clear (see Figure 6); the inside belongs to the household at whose invitation the other enters an open, fluid realm of intimacy (see Figure 7). Bedroom boundaries are somewhat ill-defined, living rooms can open to adjacent rooms, and the innermost interior is integrally linked to a private exterior. Movable walls open spaces to one another, a dining/work table bridges the kitchen and the living room, large planes of glass bring in light and views of the garden from the rear yard. The modern window wall at Mar Vista is at the rear, domesticated rather than exhibitionist in its orientation to the private yard. Thus the façade does not engage the neighbor as stranger at all, neither representing the householder to him nor forming itself around a fantasy of him. Rather, it gestures to the intimate other, the friend or neighbor who has been invited into the house: once past the front door, all is open to him.

- If an interplay of desire and danger may in a modest way be found in Mar Vista, it is as a quietly revolutionary notion of domestic life, lived as much within the private exterior and between rooms as within enclosed, utilitarian spaces with specific programs (e.g., kitchen, bedroom). The stark exterior shocked passersby; some sought this unknown future and some felt threatened by it. Mar Vista's abstraction and even disfiguring of the house transforms the specificity of its structure into a domesticated form of the sublime. At Levittown, the face of each house offers self-conscious, controlled hints of the individual within--a curtain, a railing, a vase, a rosebush in the front yard. At Mar Vista, a wall plane folds into a roof that hovers over a clerestory window; the house seems to contain space rather than people. We have little idea what lies behind the façade, except that its occupants must have made a genuine choice to be there at all. Anonymous yet apart, the houses at Mar Vista make clear that otherness is admissible. In fact, early Mar Vista was home to diverse neighbors. Residents recall that their neighbors included gay and lesbian couples, artists, working women (including a hooker), communists, union activists, musicians, Jews, interracial couples, professionals, and laborers.[17] While surely romanticized in recollection, this cacophony of others may have composed one form of the "authentic democracy" to which Gropius refers. At Mar Vista, figure and ground are ambiguous, variously perceived between the individual house and the collective whole; at Levittown, there is only the house.

- Modern architecture at the mid-century has commonly been associated with progressive or even leftist ideals.[18] Gregory Ain was a communist and, according to one study, a women's rights advocate.[19] Yet according to early residents, Mar Vista was decidedly not about politics in the formal sense. Instead, the mere atypical choice to live there gave Mar Vista residents their identity, and that appreciation of what was not-the-norm reflected and lent a tolerance for difference among "thinking people."[20] They stepped determinedly into a domestic future with their unscripted neighbors. The strangers who chose to reside in Mar Vista asssumed they had some small but profound common ground, but Ain's architecture--which was in fact that ground--does not attempt to determine or figure its content for them.

- Levittown and its modern suburban alternative, the Mar Vista Tract, laid down two distinct directions for the U.S. postwar figure of the neighbor. In the intervening six decades, it was Levittown whose figure of the neighbor evolved, replicating and mutating, but never really straying from a structural model in which the nuclear family predominates, contained by the house and controlled by regulation and a loose organization of houses in the landscape. Mar Vista's aesthetic and functional future, with its abstract public expression and more inventive private sphere, was nipped in the bud. Its dynamic, open-ended setting for self and other was not sustained in the typical suburban imaginary. The few progressive architects and planners who tried to implement innovative neighborhood schemes met stiff resistance from skeptical bureaucrats at federal and lending agencies whose approvals were required. Architectural conformity was one of the strategies such agencies employed to reduce the financial risk of mass housing.[21]

- Of course the dream of a quiet house in the garden, promised by early postwar suburbs, faltered. The actual landscape of the postwar suburb is hardly idyllic; the traffic is a nightmare; our ownership is fragile at best; politics have grown embittered; and at base, we don't feel safe in the suburbs anymore. The two suburban developments to which I now turn portray two opposed approaches to the dilemmas of contemporary suburbia. Both design approaches stem from Levittown. Each uses architecture self-consciously to form and market the development, and each has been promoted as an exemplar of contemporary residential design. The first, Sagaponac, lies on Long Island, east of its progenitor, Levittown, and when completed will consist of three dozen unique contemporary architectural works. The second, Celebration, Florida, is the brainchild of the Disney Corporation and the darling of the neo-traditional New Urbanist movement. Sagaponac takes Levittown's emphasis on the isolated house to an extreme; Celebration demonstrates that Levittown can be reclothed. Both settings interiorize and sustain the preeminence of the private household (if not of the house) while maintaining a problematic relationship to the collective public sphere.

- When developer Coco Brown decided to build on his land holdings in Sagaponack, New York, he didn't look to early models of community design, such as Radburn, or to architecturally coherent neighborhoods such as the Mar Vista Tract or Frank Lloyd Wright's Oak Park. Instead, under the advisement of architect Richard Meier, he hired a cast of some thirty-five star architects to build one-off showcase houses sited on large subdivided lots spread across his hundred acres (see Figure 8). Prospective residents would purchase one of these speculative custom designs to acquire cultural capital, take part in some hyper-suburban American Dream, and have other like-minded weekenders for neighbors.[22] As in the rest of the Hamptons, the future occupants of these second homes come from Sorkin's and Jacobs's New York City, where they must have developed a need to escape all that propinquity.

- In reaction to the failures of the postwar suburb, Sagaponac retreats further inside and away from the public sphere. While it is a subdivision, Sagaponac is hardly a neighborhood--the term seems quaint applied there. It is a collection of private, ready-to-wear statements their occupants purchase with the option of minor tailoring. Rather than being sited in a walled or gated community, at Sagaponac each house is protected by its surrounding vegetation, which naturalizes and effectively thickens the wall (see Figure 9). Gropius is cited in an essay that touts the optimism of Sagaponac's architecture: "the Houses at Sagaponac are, in their different ways, doubtlessly modern; they are surely lively, and in their heterogeneity, they are harmonic in a way that contradicts Gropius's intended meaning, but in so doing are, however imperfectly, truer to his words" (Chen 11). A convoluted apology, but not without meaning. Modern architecture at Sagaponac, the author suggests, exposes a desirable diversity, a "discrete kind of utopia" defined against the status quo and bolstered by the possibility of the new. When Gropius made his statement, he had fled persecution in Germany to seek in the U.S. freedom for political and architectural expression. No collective, political or otherwise, is imagined at Sagaponac, but the value it places on freedom for individual expression is consistent with both neo-conservative notions of an ownership society (in which owners are free to do as they please with their property) and neo-liberal versions of multiculturalism (which remove the burden of seeking collective solutions to broad social problems). This privatized utopia is hardly the "authentic democracy" Gropius meant.

- Despite the contemporaneity of its architecture, Sagaponac develops not the modern figure of the neighbor implied by Ain's houses, but the neighbor of its precursor, Levittown. Both Levittown and Sagaponac specifically interiorize the private lives of residents in vivid contrast to ill-defined exterior shared realms. While Levittown figured similar occupants of repetitive house forms, Sagaponac imagines that its residents share the fundamental quality of being highly discriminating consumers. Sagaponac intimates that its residents hold a common value: the house is an investment in art that extends one's status and wealth. The extreme demands for social conformity at Levittown are mirrored in Sagaponac's inordinate emphasis on individualism--a renowned architect, a unique building, a discriminating buyer, a solo developer. The conception of the neighbor is not the neighbor as other, but as fellow individualist.

- If it's unfair to link Sagaponac to Levittown, it is for only one reason: it does not even intend to form a community, but instead a loosely curated collection of artworks. Although their partial proximity makes neighbors of the residents, their bond will be primarily their investment in Sagaponac. The houses, designed to include their own guest houses, accommodate the idealized family isolated with its intimate friends. Outside the dwelling, Sagaponac adopts the development pattern of the masses, selling speculative houses unified only by a basic infrastructure of streets and sewers. In some ways, Sagaponac demonstrates how deeply ingrained the Levittown model of housing has become. As in the Mar Vista Tract, it isn't necessary to have a highly articulated interstitial realm in order to create spaces for the practices that emerge among proximate strangers. But it is difficult to imagine that Sagaponac residents will ever find one another, by chance or on purpose. With houses set back from the street, hidden behind trees, no sidewalks and no nearby public meeting place, Sagaponac's weekend residents will have a hard time managing a homeowners' association, should any need for one arise.

- While Sagaponac's occupants retreat into housing that respects absolute privacy, Celebration, Florida symbolically molds an idealized community. Perhaps the distinct rejection of architects by the typical suburban neighborhood has allowed new urbanism to become such a potent force in the domestic landscape. Even as the Levittown pattern of a field of isolated, interior-oriented objects tied only by roadways has gone virtually unchallenged, precisely its neighborhood elements of parks, pools, and shopping within residential blocks have been phased out. The speculative house prevailed over most American neighborhoods until 1991, when leaders of the Congress for the New Urbanism published the Ahwahnee Principles. Seaside, a contemporary neo-traditional development in Florida, became the talisman of the new urbanist movement, and a new future for neighborhood architecture took shape. This future looked nostalgically and unapologetically to a time before the car, household mobility, and big-box retail. The new urbanism would remake an older U.S. small town, resuscitating and transforming the mythos of community, simplicity, security, and so on. After having produced many books, articles, and, most importantly, newly built suburban neighborhoods, new urbanism has been soundly criticized from nearly every academic perspective and absorbed by the marketplace with profound efficacy. Such a discrepancy has not been seen since Levittown.[23]

- Celebration, new urbanism's most complete manifestation, illustrates the weird contradictions of its design ideology.[24] This suburban development near Orlando is more than a themed environment; it is wholly branded. It has borrowed the Disney name not only to insure its property values, but to create what residents call a fantasyland within everyday life. That everyday life is regulated to an unprecedented extent to present a homogeneous group of neighbors on the outside. Taking its cue from the Levitts, the Disney Corporation insures that neighbors maintain the look of neighborly sameness, from the color of their curtains to the depth of their mulch. Celebration's town plan centers around a pedestrian-oriented business district, but like the scattered neighborhood centers in Levittown, Celebration's commercial district struggles to survive. The residential architecture employs the symbols of community life: porches, small parks, playgrounds, a family of historicist architectural expressions, public benches, parkways, a couple of diners, a town hall. The town hall is empty, however, because Celebration is governed by the Disney Corporation: democracy is literally reduced to its architectural sign.[25] As for the neighbor, perhaps no place in America has so explicitly conjured a figure of the "we" through its architecture. Even private house interiors at Celebration, anthropologist Dean MacCannell argues, are organized for public view to eradicate fears that a hidden difference lurks behind the façade (113-14). In this pressure-cooked neighborhood, civility can be as superficial as brick veneer, as some bitter and well-documented battles between residents have demonstrated.[26]

- Sagaponac and Celebration, then, articulate anxiety about the neighbor. Sagaponac adopts Levittown's deployment of the detached house as the rigid container of privacy and glorifies that privacy in expressions of individuality, while Celebration extends that privacy's complement: the construction of a highly regulated and spatially defined common realm. When the figure of the neighbor is so overtly defined, informal practices of neighboring seem less necessary. In the fantasy of Celebration, it is as though one already knew one's neighbors; in the fantasy of Sagaponac, one need never meet the neighbor, assured that we share the same good taste and desire for privacy. Thus the political fruits of civility born of actual negotiation with the unknown are diminished.

- What lies beyond the paint, outside the box of domestic privacy, is uncertain turf. This space, both unprivate and unpublic, is home to the figure of the neighbor and birthplace of civil society. It is just here that we need a new conception of architectural community. Architectural critic Paul Goldberger, worried over Sagaponac's insular qualities, mustered just two counter-cases of developments from a vast repertoire of architectural examples: Radburn, built in the 1920s, and Celebration. Both, he believes, represent efforts at community-building and embody a public realm. Aware that this is not quite accurate, yet stopping short of criticizing Celebration, he goes on: "The great accomplishment at Radburn is that it creates a sense of the public realm without making the place feel in any way urban."

- Goldberger cannot name this public realm that is not urban because as yet it has no name, nor has it been defined. But he identifies it at Radburn, where there is "a fully suburban, even almost rural, kind of feeling." "Rural," "suburban," and "urban" describe this interstitial space of the neighborhood no better than "public" and "private." At Radburn the houses faced onto a shared open space that linked the development together. In more typical suburbs, neighbor-form is an ill-defined realm of side yards, curbside mail boxes, elementary school parking lots, and cul-de-sacs. These inadvertently intimate grounds give way to a nearby Starbucks, the laundromat, the city council hearing room, and the city park. This circumstantial, ad hoc, and interstitial figure of the neighbor is not easily named or programmed into architectural form. Although Goldberger recognizes it when he sees it at Radburn, he misapprehends Celebration's neighbor-coating as some Habermasian public sphere.

- Postwar residential landscapes interiorized the private sphere, giving over the visible exterior to a more formal, shared realm. In spite of the intentions of builders like the Levitts, however, the suburban house could not contain its occupants. The interiors were too small, the yards too open, and most of all, the proximity too great. An inadvertent figure of the neighbor arose whose superficial sameness distracted residents from their actual differences. The appearance of difference or otherness triggered conformist reactions, and thus emerged the informally divisive politics of the neighborhood. By contrast, at the Mar Vista Tract the figure of the neighbor remained more unscripted and left room for difference. In both settings, local politics evolved not only to represent, but also to construct group identity. Unexplored, exteriorized public identity within a neighborhood was reinforced by a collectively identified other. From the early Island Trees residents who fought the name change to Levittown to Celebration residents worrying about their teenagers at the wider area's public high school, identity and difference are constructed together.

- Here it is worth reconsidering Sagaponac, where one can predict that sizable interiors, closed exteriors (closed off by landscape as well as by orientation away from other houses), lack of proximity, and weekend-only occupation will yield little that resembles a neighborhood--only "Houses at Sagaponac," as the development is called. This would be of no consequence whatsoever if not for its ethical implications regarding the state of civil society. By the standards of such society, I would argue, residential developments hold an ethical imperative to anticipate some neighbor while stopping short of dictating or fantasizing who that neighbor is. If architecture and planning are to contribute to the formation of deliberative democracy and civil society, we should design for an emergent, as yet unknown neighborliness. Consider what might have happened at Sagaponac had Coco Brown established a continuous easement across some part of every site for a walking trail.[27] Not only would the individual retreats have been inclined to address that small gesture toward publicity, but the weekend residents would have had some alternative to the mythical ideal of household isolation. Like the unscripted front green contained by a continuous building wall at Mar Vista, such a gesture might have allowed Sagaponac to imagine itself not just as a series of buildable lots, but as a loose string of neighbors.

- The fact that neighborhood architecture is pliable--although Levittown provides the recipe for suburban settlements, at least it does so flexibly--is one of the most promising conclusions that can be drawn from these case studies. From modern to postmodern developments, from Levittown to Celebration, an observable transformation of neighborhood architecture sheds light on future paths. The next phase of neighborhood architecture will be affected forcefully by three shifting conditions: the rising significance of neighborhood politics, emerging domestic technologies, and changing conditions of regional land use that are forcing residential development into urban infill sites. These conditions place otherness in greater proximity than ever before, heightening urges to expose or to repress differences within the neighborhood. These conditions can spark new figures for the neighbor, and new bases for civil society.

"For it is a simple matter to love one's neighbor when he is distant, but it is a different matter in proximity."

--Jacques-Alain Miller (79-80)

| Figure

1: Spite Fence Eadweard Muybridge, San Francisco (1878)[1] Image used by permission of Kingston Museum and Heritage Service. |

Introduction

The Neighbor as Political Figure

"Propinquity--neighborliness--is the ground and problem of democracy."

--Michael Sorkin (4)

Sub-urbanism

American Figures

Baseline

| Figure 2: Levittown Aerial View, ca. 1957. |

| Figure 3: Levittown Floor Plan. |

| Figure

4: Levittown Street Scene. Photo by Dana Cuff (2004). |

Modernism's Figure

"A modern, harmonic and lively architecture is the visible sign of authentic democracy."

--Walter Gropius

|

| Figure

5: Ain's Aerial Perspective Rendering Image used with permission of the Architecture and Design Collection, University Art Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara. |

|

| Figure

6: Mar Vista House Photo by Dana Cuff (2004). |

|

| Figure 7: Mar Vista Floor Plan

Projection Image used with permission of the Architecture and Design Collection, University Art Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara. |

Developing Neighborhoods

Hyper-Suburbia: Designing the Neighborhood Away

|

| Figure

8: Sagaponac house designed by Hariri and Hariri Photo by Dana Cuff (2004) |

|

| Figure

9: Sagaponac house designed by Harry Cobb in the background, with a streetside marketing sign showing the architect's rendering. Photo by Dana Cuff (2004). |

Evoking the Neighbor

|

| Figure

10: View down Celebration's Market Street Photo by Dana Cuff (2004). |

|

| Figure

11: Residential Street in Celebration Photo by Dana Cuff (2004). |

Reconfigurations

Department of Architecture and Urban Design

University of California, Los Angeles

dcuff@ucla.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2005 Dana Cuff. READERS MAY USE

PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S.

COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED

INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

1. The "spite fence" was a famous landmark on Nob Hill in San Francisco. The owner of the mansion in the photo built an immense fence (so high that it required buttressing) around a less well-off neighbor. By spoiling his view and house, the landowner hoped to force his neighbor to sell his property. Today what are called "spite fence laws" prohibit such malicious actions.

2. For a discussion of neighborhood privatization, see Ben-Joseph.3. The recent national elections remind us of the political differences between city and suburb (the former voting primarily Democratic and the latter, Republican). While these data are troubling, they do not necessarily reflect the "suburban canon": the idea that suburbanites flee difference while expressing intolerance. Although the history of urban migration outward has been made up of such flight, today's suburbanites are more heterogeneous than ever and cannot easily be distinguished spatially, economically, or racially from their urban counterparts. Much of what was classified as "urban" in the election data (Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas) is suburban in form. This essay considers suburbs not because they represent some particular class of Americans, but because they are the places where most Americans live.

4. The term "community builders" comes from Weiss. "Merchant builder" is a more common term and the title of a book by Eichler, son of a prolific developer of modern houses.

5. Proxemics is a field of study that evolved from ethology in which the regular spatial patterns of human behavior are held to be most vividly portrayed in the different cultural norms of personal space. See such founding works as Hall and Sommer.

6. Arendt draws her notion of the public world of stable appearance from Kant; see her Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy.

7. My interpretation of these four places stems from existing literature and my own field work. I visited each site, photographed it, studied local archives, and interviewed residents (except in the case of Sagaponac, which is still uninhabited at the time of this writing). I agree with critics such as Paul H. Mattingly that suburban studies has not sufficiently engaged suburbanites' own stories of their communities. Residents in this project by and large expressed contentment about their neighborhoods, and gave nuanced descriptions of both social and physical spaces.

8. According to Kelly's historical account, "in the abstract, Levittown was virtually a replica of the officially recommended subdivision styles of the FHA" (47n8).

9. The original Levittown in Long Island (as opposed to subsequent Levittowns built in Pennsylvania and New Jersey) was built over a period of four years, from 1947 to 1951. The first phase, completed in 1948, was comprised of 6000 identical Cape Cods built as rental units and later offered for purchase. The next phase, starting in 1949, introduced several variations on the Ranch model. The 1950 and 1951 houses included built-in televisions; all houses had washing machines. In the end 17,500 houses were built by Levitt and Sons in Levittown (Kelly 40-53).

10. At the rear of the Ranch house, generous glazing faced the back yard.

11. 1952 Levittown Property Owners Association booklet, Levittown Public Library collection. While there remains a regulation against fences in the covenants, codes, and restrictions, at present nearly every house has a fenced rear yard.

12. See Putnam on the devolution of communitarianism to isolationism in the modern U.S.

13. Sociologist Herbert Gans reports extensively on politics and everyday life in the third Levittown, built in Pennsylvania eight years after the Long Island Levittown community. His information about volunteer organizations comes from living there as a participant observer (see especially 52-63). While he focuses on socio-economic status, Gans inadvertently tells much about the residents' ideas of otherness and the relationship between their volunteer activities and their participatory politics.

14. A resident association opposed Levitt's proposal to change the original name of the subdivision from Island Trees to Levittown. Eventually Levitt made the change unilaterally, but not before removing the resident association's permission to use the community room. Levitt was quick to shut down all opposition. He purchased the local newspaper in 1948, just when the paper took stances against several of his initiatives, including a rent increase. Levitt insinuated in a brochure that the Island Trees Communist Party had spearheaded the opposition (and it appears this may have been the case). See newspapers in the Long Island Studies Institute archives at Hofstra University and brochures at the Levittown Public Library.

15. The most obvious and significant difference is scale: Mar Vista was planned for 100 homes (of which half were built) in comparison with Levittown's 17,500. In addition, Mar Vista houses were more expensive than Levitt houses (approximately $12,000 and $8,000, respectively). Other examples of modern suburban houses include the Eichler Homes, built primarily in Northern California, and the Crestwood Hills development in Los Angeles.

16. See the surveys of residents' reasons for moving and their aspirations for life in Levittown in Gans (33, 35, 39). Information on Mar Vista residents is gathered from my interviews with original residents, 2004.

17. Interviews with early residents, 2004.

18. For a discussion of the interconnections between residential modernism and progressive social ideals, see Zellman and Friedland.

19. On Ain's political orientation, see Denzer's "Community Homes: Race, Politics and Architecture in Postwar Los Angeles."

20. On the politics of modernism at Crestwood Hills, see Zellman and Friedland. Several early residents have histories of union organizing or other leftist political activism. They imagined their primary political stance in relation to the neighborhood, however, to be one of tolerance as part of a forward-looking society. One early resident described Mar Vista as a neighborhood of "thinking people" in contrast to those who chose to live in West L.A.'s Levittown equivalent, Westchester. Still, it should not be imagined that Mar Vista was or is a model of tolerance. One resident recounted a petition drive to force an early Latino family in the neighborhood to move away. While the current population at Mar Vista still includes a few of the original buyers, residents now represent a higher income group (homes at present sell for nearly $1 million) and are afficionados of mid-century modernism as a nostalgic ideal.

21. See, for example, Zellman and Friedland on Crestwood Hills (n25). Wright discusses the Federal Housing Administration's "adjustment for conformity" criteria for evaluating housing plans (251).

22. For statements by Brown and brief essays by several authors, see Brown. The area of the Hamptons where the houses are built is called Sagaponack, but Brown named his development Sagaponac (without the k). Among the four case studies presented here, Sagaponac is unique in two important ways: it is exclusively for the wealthy, and it consists primarily of second homes rather than permanent residences. As such, it is an outlier development rather than a middle-class suburban one.

23. Even as architectural critics proclaim the death of New Urbanism (see, for example, New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff's comments on a proposed stadium), suburban developers, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and foreign planning bodies in Sweden, Spain, and China, to name but a few, are adopting its tenets.

24. See MacCannell. For more on Celebration, read the two participant observer volumes: Frantz and Collins, Celebration, USA, and Ross, The Celebration Chronicles.

25. In 2003 residents were added to the governing board and in the near future, residents will for the first time have a majority on that board.

26. An early battle over the school made Disney's control over the town evident. Residents who wanted to change school policy were dubbed "the negatives" by supporters of Disney's educational plan, silenced and evicted. See Pollan.

27. Ironically, this kind of informal public infrastructure is a dominant design component in a number of schemes by the firm Field Operations whose principal, Stan Allen, is a Sagaponac architect.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1958.

---. Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy. Ed. Ronald Beiner. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992.

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Trans. Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon, 1994.

Ben-Joseph, Eran. "Land Use and Design Innovations in Private Communities." Land Lines: Newsletter of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy 16 (Oct. 2004): 8-12. <http://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/pub-detail.asp?id=971>.

Brown, Harry J., ed. American Dream: The Houses at Sagaponac. New York: Rizzoli, 2003.

Chen, Aric. "Domestic Architecture Reborn." Brown 10-12.

Copjec, Joan, and Michael Sorkin, eds. Giving Ground: The Politics of Propinquity. London: Verso, 1999. 106-128.

Denzer, Anthony. "Community Homes: Race, Politics and Architecture in Postwar Los Angeles." Community Studies Association Conference, Pittsfield, MA, 2004.

Eichler, Ned. The Merchant Builders. Cambridge: MIT P, 1982.

Frantz, Douglas, and Catherine Collins. Celebration, USA. New York: Holt, 1999.

Gans, Herbert. The Levittowners. New York: Vintage, 1967.

Goldberger, Paul. "Suburban Chic." Interview with Daniel Cappello. The New Yorker 6 Sept. 2004 <http://www.newyorker.com/online/content/?040913on_onlineonly02>.

Hall, Edward T. The Hidden Dimension. Garden City: Doubleday, 1966.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage, 1961.

Jameson, Fredric. "The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism." Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke UP, 1991. 1-54.

Kelly, Barbara M. Expanding the American Dream: Building and Rebuilding Levittown. Albany: State U of New York P, 1993.

MacCannell, Dean. "New Urbanism and its Discontents." Copjec and Sorkin 106-128.

Mattingly, Paul H. "The Suburban Canon over Time." Suburban Discipline. Eds. Peter Lang and Tam Miller. New York: Princeton Architectural, 1997. 38-51.

Miller, Jacques-Alain. "Extimité." Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure and Society. Ed. Mark Bracher. New York: Routledge, 1994. 79-80.

Ouroussof, Nicolai. "A Sobering West Side Story Unfolds." The New York Times 1 Nov. 2004: E1.

Pollan, Michael. "Town-Building Is No Mickey Mouse Operation." New York Times Magazine 14 Dec. 1997: 56-88.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon, 2000.

Ross, Andrew. The Celebration Chronicles. New York: Ballantine, 1999.

Schudson, Michael. Advertising, the Uneasy Persuasion. New York: Basic, 1984.

Sommer, Robert. Personal Space: The Behavioral Basis of Design. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1969.

Sorkin, Michael. "Introduction: Traffic in Democracy." Copjec and Sorkin 1-15.

Weiss, Marc. The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning. New York: Columbia UP, 1987.

Wright, Gwendolyn. Building The Dream: A Social History of Housing in America. New York: Pantheon, 1981.

Zellman, Harold and Roger Friedland. "Broadacre in Brentwood? The Politics of Architectural Aesthetics." Looking for Los Angeles: Architecture, Film, Photography, and the Urban Landscape. Eds. Charles Salas and Michael Roth. Los Angeles: Getty, 2001. 167-210.