Grand Theory/Grand Tour: Negotiating Samuel Huntington in the Grey Zone of Europe

Dorothy BarenscottUniversity of British Columbia

bridot@shaw.ca

© 2002 Dorothy Barenscott.

All rights reserved.

- In 1996, the Russian based photo-conceptualist group AES (made up of

artists Tatyana Arzamasova, Lev Evzovitch, and Evgeny Svyatsky) launched its

"Travel Agency to the Future" with the Islamic Project. Promoting a

set of fictitious Grand Tours which would set out in the year 2006 into a

radically changed and dystopic landscape, AES drew inspiration from Samuel

Huntington's popular political paradigm of the mid 1990s, which anticipated the

time when Islamic and Western cultures would come violently into

collision. Well before

the events of September 11th and well before George W. Bush's "crusade against

terror," AES prepared clients for travel to the future through advertising and

promotional material that featured fantastic projections of what the new world

order would bring. More specifically, AES produced a series of digitally altered

images, in the form of postcards, depicting the monuments and spaces of familiar

tourist destinations (such as those found in Paris, Rome, Berlin, and New York)

invaded, occupied, and altered by Islamic civilization. Not surprisingly, AES

images were scattered among the many "ground zero" photographs widely circulated

on the Internet in the days and weeks following the attack on the World Trade

Center--a specific moment when a "Western" public was made to confront its own

fears of an "Islamic" Other (see Figure 1).[1]

Over the past five years, AES, the agency, and its promotional material have been set in a variety of locations and spaces each with its own set of complexities, be they the spaces of the gallery, the spaces of the street, or the virtual spaces of its agency website on the World Wide Web.[2] Central to the Islamic Project is the constructed tension between "East" and "West," a monolithic paradigm and theoretical concept that works strategically at many levels, be they geographic, economic, cultural, or political.

Figure 1: New Freedom (2006)

Copyright © AES & GRAF d'SIGN 1996 - The unique position of AES, as a group of Russian artists, to begin exploring, problematizing, and articulating what is at stake in the construction of an East/West split emerges out of its own status as postcommunist citizens in what Piotr Piotrowski terms the "grey zone of Europe" (37). Therein, the processes and rhetoric of globalization and multiculturalism have played out on the terrain of a hotly divided and increasingly nationalistic social body where geographic tensions have undermined the West's call for a harmonizing of all divisions--a united Europe. We can begin to unpack AES's use of the conventions and identity of a travel agency and the circulation of postcards and other tourist objects as a productive way to explore, question, and problematize both the tourist gaze and the gaze of the global consumer--forces which activate and reinforce the East/West divide on many levels. As such, AES's images operate at progressive degrees and within multiple layers of desire, beyond the broader desire to travel and to consume. They are entangled with the intellectual crisis of a post-Soviet world coming to grips with issues of national and individual identity, the changing dynamic of cultural representation, and the removal of borders (physical, theoretical, cultural, and economic) in everyday life. Therefore, AES's Islamic Project can be read in relationship to a range of issues stemming from the articulation of difference through the guise of tourism and the ways in which the East/West divide is capitalized upon and upheld, and to what ends. These issues relate directly to AES's use of the manipulated image as a medium of cultural exchange, the spaces in which AES operates and proliferates its messages, and the kinds of monuments and places that are digitally altered and reconfigured within AES's artistic practice.

-

The impetus behind the project's conception was the emerging body of

political theory in the mid-1990s that forecast new directions for

American foreign policy and global relations. In the post-Cold War era,

political scientists and government strategists began to formulate new

theories about the state of future global affairs. Francis Fukuyama was

among the most infamous for his announcement in 1992 of the "end of

history" and the triumph of liberal democracy. But beginning shortly

after the Gulf War when America and its Western partners faced combat

with a new Eastern enemy, Fukuyama's grand theory was quickly eclipsed by

that of Samuel Huntington, Harvard Professor and Chairman of the Harvard

Academy for International and Area Studies. In a 1993 article

for Foreign Affairs titled "The Clash of Civilizations?,"

Huntington sketched out what would become arguably the most influential and highly

controversial political theory governing American foreign relations in

the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. In

the opening passage of the article, Huntington declares a radical

reconceptualization of politics (indeed for the discipline of political

science itself). He states:

World politics is entering a new phase, and intellectuals have not hesitated to proliferate visions of what it will be--the end of history, the return of traditional rivalries between nation states, and the decline of the nation state from the conflicting pulls of tribalism and globalism, among others. Each of these visions catches aspects of the emerging reality. Yet they all miss a crucial, indeed a central, aspect of what global politics is likely to be in the coming years.

It is my hypothesis that the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. Nation states will remain the most powerful actors in world affairs, but the principal conflicts of global politics will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations. The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be the battle lines of the future. (22) - Huntington goes on to count a number of civilization "identities," which by the time of his 1996 book-length treatment of the original article (The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order) numbers nine: Western (by which he means Christian and liberal-capitalistic); Latin American; African; Islamic (where he includes Indonesia as well as the Middle East and the northern half of Africa); Sinic (including China and cultures descended from it, e.g., Korea and Vietnam); Hindu; Slavic-Orthodox (i.e., Catholicism as localized in Russia in the late Middle Ages); Buddhist; and Japanese. With strong claims that conflicts will emerge as alignments of the "West against the Rest," and especially the West against Islam, Huntington appeals to Western civilizations to join against the common enemy. He sets out a number of goals, including the incorporation of Eastern Europe and Latin America into the West, the pursuit of cooperative relations with Russia and Japan, and the strengthening of international institutions that reflect and legitimate Western interests and values. Moreover, Huntington lists a number of "fault lines" of the world, relying heavily on examples from conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, to illustrate and support his overall argument that "as people define" their civilization-consciousness, "they...likely...see an 'us' versus 'them' relation existing between themselves and people of different ethnicity or religion" (25).

-

Indeed, what Huntington constructs through the various permutations of

his argument is a paradigm--one that posits culture in all

its subjective ambiguity as the distinguishing trait of

political struggle. But perhaps more problematically,

Huntington leaves open the question of whether his clash

thesis places civilizational conflicts beyond the power and

means of mediation through political partnership (e.g., the

United Nations or NATO) and/or diplomacy. He therefore

appears to suggest that all civilizations should live in

peace with one another at the same time as claiming

their inability to reach mutual compromise. In the end,

Huntington's paradigm leaves the onus of successfully

disavowing his theory upon those who can formulate a better

hypothesis. Borrowing from Thomas Kuhn's discourse on

scientific revolutions, Huntington establishes a highly

convincing master system built upon a monolithic set of

predetermined "truths."[3]

However, as critics have noted, these "truths" actively distort the

vastly complex issue of globalization. Within the United States, much of

the debate since 1993 has been limited to certain aspects of the clash

thesis, seldom broaching the fundamental question of whether Huntington's

views are in fact dangerous and even racist.[4]

Therefore, the most vocal and sustained opposition to Huntington has

emerged from non-Western scholars, none of whom has exerted anywhere near

the kind of influence that Huntington has in American foreign policy

circles. Publishing in lesser-known journals or small collaborative

collections such as "The Clash of Civilizations?" Asian

Responses (published in 1997 in Karachi, Pakistan through Oxford

University Press), these scholars established the discourse for the

earliest critiques of the clash thesis, underscoring the very real

consequences that such a paradigm holds and drawing out the weaknesses

and potential danger inherent to adapting Huntington's model to

transglobal relations. As Salim Rashid notes in the introduction to

The Clash of Civilizations?: Asian Responses,

In the long sweep of history, Europe has continually looked with trepidation upon Asia. Whether it be the attacks of the Persians upon the Hellenes, or the Moors who long ruled Spain or the Ottomans at the gates of Vienna or the Mongols sweeping through Poland and Hungary, it is Asia that has continually threatened Europe with destruction. While three hundred years of European dominance have dimmed these memories, Samuel Huntington has succeeded in a charming revival of a long historical tradition. In an article entitled, "The Clash of Civilisations" one is struck first by the definite article in the title--not "A Clash" but "The Clash." (i)

- This insistence upon empiricism in Huntington's arguments, the claim to describing the reality of the world, is at the core of critics' concerns since these claims revive a tradition of viewing the East, the Other, in highly mythologized and problematic ways. Therefore, if critics charge Huntington with escapism, reductivism, isolationist politics, racism, and fear-mongering, what lies at the heart of these concerns is the way Huntington mobilizes and trades in cultural myths to support his thesis.

- In this connection, it is useful to recall Roland Barthes's analysis of myth in the section of Mythologies called "The Form and the Concept." "In myth," Barthes writes, "the concept can spread over a very large expanse of signifier. For instance, a whole book may be the signifier of a single concept; and conversely, a minute form (a word, a gesture, even incidental, so long as it is noticed) can serve as signifier to a concept filled with a very rich history" (120). Here Barthes stresses the uneven nature of mythic constructs. What's more, he describes these concepts as lacking fixity so that "they can come into being, alter, disintegrate, [and] disappear completely" (120). Barthes positions the distinguishing character of the mythical concept as something that is appropriated and recycled. In this way, what remains "invested in the [mythical] concept is less reality than a certain knowledge of reality" (119)--one that is often ahistorical and contingent upon shifting power relations. As Barthes goes on to state: "In actual fact, the knowledge contained in a mythical concept is confused, made of yielding, shapeless associations" (119). These aspects further situate the myth-making process as an act of deliberate distancing without clear fixity or return to origins, an ephemeral power of disconnection.

- But more importantly, Barthes' analysis points to the inherent instability of the uneven processes through which cultural differences are most often communicated and internalized. And while the staging of AES's critique has manifested far beyond the original concerns of the non-Western critics, as we shall see, it is arguable that the first step to unpacking AES's engagement with Huntington circulates around this Barthesian sense of the mobilization of myths. Indeed, embedded in the very sign system of culture are a myriad of such myths that make Westerners feel secure when images of Islamic men shaving off their beards or Muslim women applying make-up signals the triumph of the West in its "war on terror." These cultural differences and the way they are signified, experienced, and circulated through media projections, fantasy scenarios, and manufactured myths of all kinds form a key construct of AES's Islamic Project.

- Chris Rojek, in his provocative article "Indexing, Dragging and the Social Construction of Tourist Sights," describes the position of the "extraordinary place" as a social category in these very terms--places that "spontaneously invit[e] speculation, reverie, mind-voyaging, and a variety of other acts of imagination" (52).[5] What is undoubtedly immediate in the AES images is that each depicts a spatial location already richly embedded with the aura of the extraordinary, holding a powerful draw to the average tourist--places such as the Statue of Liberty, Notre Dame Cathedral, Disney World, Sydney Harbor, Red Square, etc. Yet, as Rojek points out, these sites also abound in a "discursive level of densely embroidered false impressions, exaggerated claims and tall stories." It thus becomes "difficult... to disentangle" the "tradition of deliberate fabrications from our ordinary perceptions of sights" (52). Therefore, in order to make these sites legible, the tourist must draw on a whole range of conflicting signs to construct what is being seen. This process involves activating the tourist's familiarity with and relationship to the place through a configuration of these signs. And while this "activation" remains largely an abstract endeavor, often facilitated through media imagery, it does implicate very material spaces and contexts.

-

Rojek's specific discussion of indexing and dragging provides a fertile

stopping point in this analysis. Here, Rojek appears to invoke the

practice of clicking and dragging a computer's mouse to help

explain the process through which tourists apprehend the "extraordinary" or the

"different." In this model, indexing refers to a kind of inventory-taking

of all the visual, textual, and symbolic representations to the original

object (e.g., in Los Angeles, one might think of the Hollywood sign, the

L.A. riots, the L.A. of Beverly Hills Cop, the TV show

Melrose Place, palm trees, and Marilyn Monroe--not a uniform

procedure by any means). Importantly, Rojek stresses that indexing takes

account of metaphorical, allegorical, and false information resources,

"interpenetrat[ing] factual and fictional elements" in order to

"frame the sight" (53). The term "dragging" is thus evoked as both

an abstract and a corporeal experience that illuminates the complex

feelings one encounters as a tourist. Specifically, "dragging refers

to the combining of elements from separate files [or indices] of

representation to create a new value" (53). As Rojek explains, dragging

is often facilitated "through tourist marketing, advertising, cinematic

use of key sights and travellers tales" (54). The result is that a

superficial/surface relationship emerges in relationship to the place,

creating one extraordinary site after another in a laundry list of

sites to explore and engendering a kind of blasé attitude toward the

places of travel as well as a constant state of distraction:

The desire to keep moving on and the feeling of restlessness that frequently accompanies tourist activity derive from the cult of distraction. Pure movement is appealing in societies where our sense of place has decomposed and where place itself approximates to nothing more than a temporary configuration of signs. (71)

- Notions of the touristic quest for authenticity as outlined by Dean MacCannell in The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (1989) are thus problematized specifically because the process of indexing and dragging precludes any attempt to experience any "real" place. As such, the restless nature of tourism is precisely envisioned by Rojek as the process of quickly moving from sight/site to sight/site, drawing on Virilio's emphasis that velocity, as a "potent source of attraction in contemporary culture," outstrips any temporally prolonged engagement with any one place (71). Importantly, Rojek distinguishes and continually stresses the important place of myth in all travel and tourist sites. This link emerges as a result of the physical remoteness of most tourist sights to the traveler and the accompanying speculation of the unknown, including the "fantasy about the nature of what one might find and how our ordinary assumptions and practices regarding everyday life may be limited" (53). Therefore, myths can come into play as a way to apprehend the unknown, to fill in the patches of what cannot be understood or ascertained.

-

Within AES's Islamic Project, these elements of

re-presentation, tourism, and myth are strongly punctuated. First, in

relationship to indexing, AES provides the photograph, index par

excellence, and loads its images with a veritable file of indices (the

effect of montaging multiple photographs) of both the West and of Islam.

Importantly, distinctions are kept firmly within a binary of

re-presentation. The West is most often signified in the images through

its institutions, technology, and modernity, while Islam is pictured as

traditional, religious, aggressive, and ubiquitous (I am thinking here

specifically of the many Muslim bodies filling several of the images,

tapping into Western anxieties and stereotypes about immigration and the

fear of being outnumbered--see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rome, (2006)

Copyright © AES 1996 - Second, it is important to note that each of the digital photographs is created with existing imagery (appearing to fulfill the appropriating function highlighted by Barthes) and thus represents a kind of assemblage produced by indexing and dragging. This lends the images a feeling of familiarity, making them seem safe, yet still fantastical. Third, the familiarity of the images is further evoked through their seriality. The tourist can anticipate where some of the stops will be and begin the process of quickly looking from one image to the next, anticipating the next place, distracted from engaging with any one image. This sparks the process of movement, acceleration, and distraction in an attempt to apprehend the entirety of what is being presented and to collect or check off each site/sight visited. Fixity is further removed with the proliferation and flow of multiple objects in multiple forms (postcards, t-shirts, mugs, posters), objects that provide evidence of the visit while constructing new indices and contexts for re-presentation. And adding still further to the familiarity and seriality of the images is the distinctive green logo mark referencing Benetton's "United Colors of the World" campaign (see Figure 3)[6], raising another aspect of Rojek's argument, the rise of "neo-tribes" or new virtual collectives in which social identity is expressed and recognized in conditions of anonymity and disembodiedness (61-62).

-

In this way, the logo, itself a complex sign, signals the consuming

aspects of tourism supported by a global economy and travel industry

penetrating every corner of the globe. And, as Mika Hannula argues in his

short essay "The World According to Mr. Huntington," the problematic

success of the clash thesis emerges in a world where consumer behavior

demands convenience:

There was the demand and voilà, before you could stutter ch-ch-ch-cheeseburger, there also was the supply. There was a huge demand for an answer, a schema that would explain the world in these chaotic, insecure post Wall times. There was fear, and there was uneasiness in the face of a pluralist, multicultural world awash with contingency. The fear was fuelled by images of rebels from far-off lands, and with hard-to-spell names, bluntly labelled Islamic fundamentalists' [sic] and, quite obviously, terrorists.... On the face of it, these claims do in general have strong argumentative force. They support deeply rooted prejudices, and help explain the world order, or disorder, and all the threats you feel when watching the evening news presented in a compact, consumable, comprehensible way. (4)

- Hannula touches here upon two key concepts worked through the Islamic Project.[7] First, Hannula underscores the relationship between consumer culture and the mass media in shaping ideas about cultural difference. Second, there is a suggestion of interactivity and contingency pointing to the type of virtual mobility that today's consumer can access through ever increasing and complex means. In turn, both dynamics relate to ideas around exchange and travel. And since it is through the theoretical and conceptual spaces of travel and tourism that most cultural differences can be and often are marked out, AES's choice to take up the identity of a travel agency, one which trades in images of difference, comes into clearer focus.

-

Reading AES's images in this context points to a number of important

implications relating not only to the use of manipulated photographs and

their relation to the social construction of touristic space, but also to

the emerging cultural milieu of postcommunist Europe where newly opened

borders allow for travel (both physical and imaginary) in both

directions. In the context of these connections, we can ask what is the

significance of an altered image, how is it conceived, and what does its

relationship to the production and signification of difference mean?

Moreover, we can explore how the circulation of that image, or a series

of related images, calls up the mobilization of a tourist gaze and

sensibility, and to what ends. As a mock travel agency, AES is able to

stage the elements of tourism both inside the gallery and on its

interactive website. In the gallery, the images are shown in postcard

stands and on consumable items such as t-shirts and mugs (which can be

purchased, becoming souvenirs of the exhibit). The artists, dressed as

travel agents, mill around, passing out questionnaires (see Figures 4 and 5).

Providing a nondescript corporate name, AES does not register the agency's Russian identity or artist identity any more than the promotional material or questionnaires (all of them in English) do. The corporate identity, streamlined office space, and glossy promotional materials create an environment of familiarity and comfort for the largely Western audience of gallery goers and tourists, new not only to the clash thesis but to postcommunist art as well.

Figures 4 & 5:

Photographs from inside

the 1997 Installation of Islamic Project in Graz, Austria.

Copyright © AES 1997 - This performance has the effect of distancing both the cultural identity of the artists and the subject matter of the individual images. In this way, the agency's visitors are initially distracted from the political undertones of the work and made to feel as consumers. To be sure, the exhibit as a whole becomes one of a number of sights that a gallery visitor sees. In Budapest, where AES installed their agency at the After the Wall show of "Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe" in 2000, the irony of consuming and touring cultures was played out when gallery employees gave perfume samples of Warhol perfume to gallery goers visiting the Andy Warhol show upstairs from After the Wall. AES and other postcommunist artists surely noted the irony of having its work upstaged and out-marketed by the American cultural export.[8]

- On the Islamic Project website, the visitor encounters the touring and consuming dynamic somewhat differently when asked the question "Where do you want us to take you?," an appropriation of Microsoft's "Where do you want to go today?" trademark. Once inside, the visitor is presented with a map of the world. Prompted to click on geographic regions, the viewer is presented with a series of images and links, creating the effect of quickly moving from site/sight to site/sight. While on the home page, the visitor is confronted with a whole range of fictional and factual information that has been dragged into one frame, none of which is easy to discern (critical essay of Huntington, pictures of Muslim individuals, accounts of AES activities, order forms for AES merchandise, contact information that does not work, and the agency questionnaire).[9] The very language of travel is elucidated through and embedded in the medium of the World Wide Web at successive levels with notions of discovery, exploring sites, surfing, bookmarking places, sending messages, e-cards, etc.

-

Returning to Huntington's paradigm, it is clear that cultural difference

explored through the rhetoric, gestures, and construction of such a

tourist gaze facilitates a mode of political engagement far removed from

the specificity of place or history. The role of nation and civilization

myths are therefore central to any analysis of cultural difference

dependent on the model I've sketched out. This is a crucial aspect of

Huntington's hypothesis since it allows stereotypes and oversimplified

binary divisions to mask the complexities of the global age in which

we live. This in itself is an important political strategy, one all too

familiar to a postcommunist public shifting between political ideologies.

As such, problematizing and exposing another aspect of AES's project,

that of the fault lines between Eastern and Western Europe, links AES's

more abstract critique of Huntington with a wider geo-political conflict

emerging in Europe. Piotr Piotrowski's description of Central and Eastern

Europe as the "grey zone" is apt and telling in this regard. After the

collapse of the Berlin Wall, any uniting ideological structures were not

only abandoned in Eastern Europe but also made suspect to a high degree.

For this reason, the urgent endeavors of the liberal democratic "West" to

fold in the "East" have often been met with resistance and hostility.

As Piotrowski writes, "the historico-geographical coordinates of Central Europe

are in a state of flux... we are between two different times, between two

different spatial shapes" (36). This state of affairs, in all of its

complexity, is often too much to register. In interviews with a Ukrainian

e-journal, AES likened Russia to a "porridge," a confusing muddle of

interests that "you cannot make...out" ("AES Today"). Moreover, AES taps

into the psychological minefield of the Chechen War through its montaged

imagery portraying a civil conflict riddled with ambiguity and paradox, leaving

individuals to grapple with who the enemy really is:

Chechnya is a unique phenomenon that is not considered by the civilized society from conventional aspects. Because Russia does not understand itself what Chechnya is--minority or terrorists. Even the Russian authorities do not have such ideas. What can we say, then, about intellectuals who are absent as such in Russia now? Now...they are just silent. ("AES Today")

- What remains then is a deep intellectual crisis--a crisis where

the notion of reality is what is most at stake. This crisis registers in AES's

images in a number of striking ways, not surprisingly when the tourist gaze is

momentarily suspended and the images critically interrogated to consider the

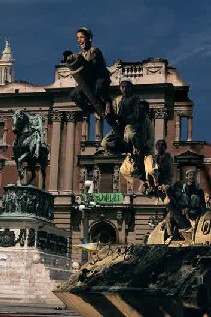

importance of place. First, it is notable that when mapped out, the most violent,

confrontational images converge precisely in the grey zone of the East/West split,

what Huntington terms the "fault lines" of Europe. Notably, the Moscow (see

Figure 6),

Belgrade (see Figure 7), and Tel Aviv (see Figure 8) series illustrates the most

violent

conflicts, where the viewer is made to experience the clash of civilizations in a

very direct and bodily way.

Figure 6: Moscow, Red Square, (2006)

Copyright © AES 1996

Figure 7: Belgrade, Serbia, (2006)

Copyright © AES 1998

Here, the hacked-off hands of enemies, advancing tanks, and children astride canons underscore the local and specific bloody conflicts seen in the wake of postcommunism. The images are generally zoomed-in, with figures confronting the camera. The most confrontational gaze is strategically placed in Moscow, where one is made to consider on which side the Muslim Chechen-like fighters belong--East or West. Moving geographically outward, the images tend toward progressive abstraction as people appear more distant and then finally removed altogether at the sites furthest from the fault lines (see Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 8: Tel-Aviv, (2006)

Copyright © AES 1996

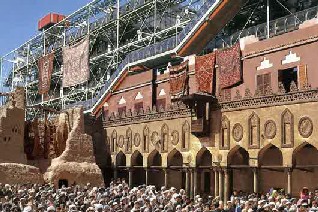

Here we are left with images that register an excess of signs, punctuated in the New Freedom 2006 image (recall Figure 1), where gender, religion, ideology, and culture are conflated into one penultimate, monolithic mega-sign of the clash between West and East. It is notable that AES took its travel agency to the streets of Belgrade and the Austrian city of Graz (see Figures 11 and 12), two cities signifying the imaginary dividing line between Eastern and Western Europe, while choosing to show only in the conceptual spaces of the gallery in America and Western Europe.

Figures 9 & 10:

New York (2006) and Sydney (2006)

Copyright © AES 1996 -

In the final analysis, there is a peculiar ambivalence that emerges in the Islamic Project precisely because of the struggle AES encounters in its role as a group of Russian artists trying to find a place for critique. Emerging from the underground, from a time when art was made to fight crippling ideology, AES saw something familiar in the work of an American political scientist wishing to postulate a new paradigm to replace Cold War rivalries. Victor Tupitsyn, in an evaluation of the "Soviet mythologizing machine" reminds us of the process of Stalinist-era derealization as eerily familiar to our own world where, awash in images and sound bytes, we often stand dumbfounded:

the 'victory' over reality belonged to those who, firstly, controlled its representation and secondly, neutralized suspicions of the existence of its Other (i.e., the other of representation). Such suspicion was 'cured' and is still being 'cured' by hypnotizing us through the magic of repetition inherent in mass printing and by our inferiority complex in the face of huge numbers, large scales, and long distances, which manifests itself in the inability to distinguish between much and all. (82)

-

For Edward Said, it is precisely the reckless disregard for criticality that he fears in Huntington's work. He argues that the "Clash of Civilizations," like a bad take-off of Orson Welles's "The War of the Worlds," is "better for reinforcing defensive self-pride than for critical understanding of the bewildering inter-dependence of our times" ("Clash of Ignorance").

-

For AES, it seems that the place for criticality may indeed be receding, as its work circulates in ways and in contexts that it cannot control. Removed from the spaces of its mock travel agency, AES's images travel precariously and within the same uneven process of indexing and dragging that it seeks to question. And indeed, with the events of September 11th, the issues taken up through AES's Islamic Project have found a particular currency, positing its work as somewhat prophetic if not completely disturbing. To be sure, AES has been and will continue to be made to answer for their art. In a recent statement posted on the website of the Sollertis Gallery in Toulouse, France, AES attempts to make sense of its predicament:

When horrible terror broke out in America our artistic phantasm grotesque of 1996 seemed real and Mr. Huntington appeared to be right, we could feel as artists that [we] became prophets. But now all of us understand that revenge for the events in America would not be the last link in the chain, but the start of the 21st century history when mankind has to solve the problems of coexistence in [a] global world of poor and rich, religious and consumer societies. The project is neither anti-Islamic nor anti-Western, but tries to function as a psychoanalytical therapy in which phobias from both Western and Eastern society are uncovered and work[ed] through. In "Islamic project: AES--The Witnesses of the Future" we tried to reveal the contradictial [sic] ethics and aesthetics of our times. We believe that contemporary art does not solve the problems, but it can raise the major questions. (AES)

Department of Art History, Visual Art, and Theory

University of British Columbia

bridot@shaw.ca

COPYRIGHT (c) 2002 Dorothy Barenscott. READERS MAY USE PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTIONS MAY USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE. FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO PROJECT MUSE, THE ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

1. Immediately following the events of September 11th, a wide and diverse number of e-cards, amateur, professional, and media photographs, and existing images related to the sites of the attacks circulated as e-mail attachments and links to impromptu memorial websites worldwide. Unaccredited AES images, often surfacing as satirical e-cards or mixed in with a stream of actual photographs, were among those circulating as a part of this phenomenon. I immediately recognized the images as the work of AES because of a trip I had made to Budapest in July 2000, where I first viewed the digital photographs displayed in the travelling exhibition After the Wall: Art and Culture in Postcomunist Europe. However, most people who received these images in their e-mail or ran across them on these memorial sites were not aware of the intended conceptual nature of the images, nor of their specific context in relation to AES's Islamic Project. The AES image I found most widely circulating was New Freedom 2006 (see Figure 1). Yet it is precisely the ephemeral and shifting nature of the World Wide Web with its various image search engines and endless e-card links that prevents me today from tracking down and tracing the sources and current locations of these e-cards and remote websites where I first came across the AES images. I credit and would like to thank Dr. John O'Brian for encouraging me to write this essay as a way to think through the intersection of photography, tourism, and the spaces of travel.

2. The AES website can be found at <http://aes.zhurnal.ru/>.

3. There are many indications of Huntington's connection to Kuhn, short of their real-life friendship. For a careful critique and analysis of Huntington's use of Kuhn's model, see Hammond.

4. The popularity of Samuel Huntington's thesis only continues to grow in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington D.C., and with today's escalating crisis in the Middle East.

5. Here, Rojek too is thinking of a Barthesian understanding of myth. Rojek writes, "Mention of the mythical is unavoidable in discussions of travel and tourism. Without doubt the social construction of sights always, to some degree, involves the mobilisation of myth (Barthes 1957)" (52).

6. I have seen AES postcards presented with and without the logo. I have provided an example of one that does have the distinctive green striping.

7. A copy of Hannula's article is reproduced on the AES website.

8. The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, PA, in partnership with the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, organized Andy Warhol, the comprehensive retrospective exhibit of Warhol's work, which began its international touring life in January 2000 and continues through spring 2002. The exhibition began at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, Russia, before moving on to venues in Turkey, Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. For the full State Department press release, complete with dates and an explanation of the initiative, see <http://secretary.state.gov/www/briefings/statements/2000/ps000118.html>.

9. When I began writing this essay, I attempted to contact AES for an interview. I quickly realized that the various contact information and e-mail addresses posted on the Islamic Project website were not operative. Likewise, if you attempt to fill out and submit the online questionnaire, the program refuses to fill in the fields.

10. This date, of course, continues to change, and the specific context may not be as clear-cut as I suggest. However, I think it significant since many Central European nations focus so much of their media attention on the future of EU inclusion and on the importance of that end date. In 1996, when AES conceived the Islamic Project, the projection was for ten years into the future with some anticipation of a larger and more powerful European Union.

11. This black-market trade in "fakes" exposes further complexities of the East/West construction. Naomi Klein, writing in The Guardian only a month after September 11th, explains:

Maybe a little complexity isn't so bad. Part of the disorientation many Americans now face has to do with the inflated and oversimplified place consumerism plays in the American narrative. To buy is to be. To buy is to love. To buy is to vote. People outside the U.S. who want Nikes--even counterfeit Nikes--must want to be American, love America, must in some way be voting for everything America stands for.

This has been the fairy tale since 1989, when the same media companies that are bringing us America's war on terrorism proclaimed that their TV satellites would topple dictatorships. Consumers would lead, inevitably, to freedom. But authoritarianism co-exists with consumerism, and desire for American products is mixed with rage at inequality.Works Cited

AES. "Islamic Project: AES Witnesses of the Future." Artist Statement. Galerie Sollertis Online November 2001: 1 par. <http://www.sollertis.com/AESWitnesses.htm>.

---. "AES Today." Interview. Boiler Online 3-4 (1999) <http://www.boiler.odessa.net/english/34/>.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill, 1957.

Hammond, Paul Y. "Culture Versus Civilization: A Critique of Huntington." The Clash of Civilizations?: Asian Responses. Ed. Salim Rashid. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford UP, 1997. 127-149.

Hannula, Mika. "The World According to Mr. Huntington." SIKSI The Nordic Art Review 12 (1997) <http://aes.zhurnal.ru/isartic.htm>

Huntington, Samuel. "The Clash of Civilizations?" Foreign Affairs 72.3 (1993): 22-49.

---. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon, 1996.

Klein, Naomi. "McWorld and Jihad." The Guardian 5 Oct. 2001: 13 pars. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/waronterror/story/0,1361,563579,00.html>.

Piotrowski, Piotr. "The Grey Zone of Europe." After the Wall: Art and Post-Communist Europe. Eds. Bojana Pejic and David Elliott. Stockholm: Moderna Museet Modern Museum, 1999. 37-41.

Rashid, Salim. "Introduction." The Clash of Civilizations?: Asian Responses. Ed. Salim Rashid. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford UP, 1997. i-iv.

Rojek, Chris. "Indexing, Dragging and the Social Construction of Tourist Sights." Touring Cultures: Transformations of Travel and Theory. Eds. Chris Rojek and John Urry. London: Routledge, 1997. 52-74.

Said, Edward. "The Clash of Ignorance." The Nation 22 Oct. 2001: 15 pars. <http://www.thenation.com/doc.mhtml?i=20011022&c=1&s=said>.

Tupitsyn, Victor. "The Sun Without a Muzzle." Art Journal 53.2 (1994): 80-84.

In conflicts between civilizations, the question is "What are you?" That is a given that cannot be changed. And as we know, from Bosnia to the Caucasus to the Sudan, the wrong answer to that question can mean a bullet in the head.

--Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations (1996)

If the search for difference is widely presented as a tourist attraction, it is obvious that cultural differences are being negated. The new types of difference that emerge are hard to identify and require too much time to decode.

---Chris Rojek, Touring Cultures (1997)

|

| Figure 3:

Northern Germany, (2006) Copyright © AES 1996 |

...the attachments are basically superficial and have the propensity to be reconfigured in response to the opportunities of contingency. In consuming this experience neo-tribes recognise that their attachments can be pulped and reconstituted to form other temporary attachments elsewhere. Mobility rather than continuity is the hallmark of this psychological attitude, and restlessness rather than anxiety defines this emotional outlook. (61)

|

|

| Figures 13 &

14: Photographs of the Travel Agencies in Belgrade (1998) and Graz (1997) Copyright © AES 1998 and 1997 |

|

|

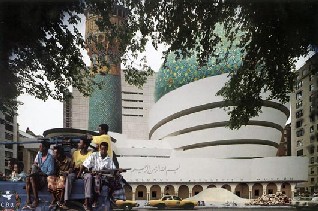

| Figures 13 &

14: Gugenheim [sic] Museum, NYC, (2006) and Paris, Beabourg [sic], (2006) Copyright © AES 1996 |

Here, AES presents powerful stereotypes that suggest both the ghettoizing of Eastern European art and the guerilla tactics artists must employ to fight the myths of their identity. This tension emerges in relation to the Benetton logo with the significant 2006 date, the projected deadline for final European Union acceptance of several Eastern European nations.[10] The appropriated logo also references the many forged name-brand goods produced and marketed in the "East" on the black market--the monies with which many operative groups fund their "terrorist" activities.[11]