Cannibalism and the Chinese Body Politic: Hermeneutics and Violence in Cross-Cultural Perception

Carlos RojasUniversity of Florida

crojas@ufl.edu

© 2002 Carlos Rojas.

All rights reserved.

-

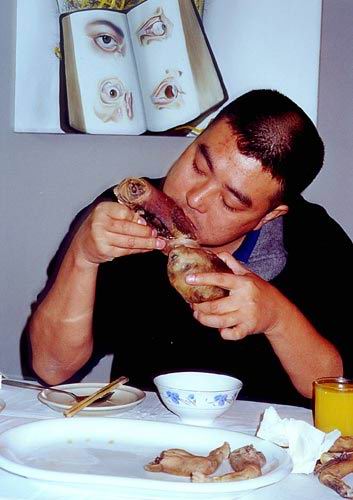

Rumors of cannibalism began to circulate over the internet during the early

months of last year (2001), typically accompanied by graphic photos of a Chinese

man calmly chewing on what appears to be a dismembered human fetus (see Figure 1),

together with sensational commentary along the lines of:

What u are going to witness here is a fact, don't get scared !" It's Taiwan's hottest food..." In Taiwan, dead babies or fetuses could be bought at $50 to $70 from hospitals to meet the high demand for grilled and barbecued babies ... What a sad state of affairs!! ("Fetus")

- These internet rumors began to achieve a modicum of legitimacy in mid-March, when the small Malaysian tabloid Warta Perdana fed a growing international controversy in reporting that a certain Taiwanese restaurant was serving a dish consisting of the baked flesh of human fetuses. The story eventually precipitated such an uproar that the CIA and Scotland Yard ultimately got involved to try to sort things out.

- While these allegations of cannibalism were, at a literal level, apocryphal, they are nevertheless quite instructive. The rumors themselves, together with the morbid transnational fascination that fed them and allowed them to grow, are interesting for two reasons. First, these rumors did not spring up in a vacuum, but rather they are implicitly in dialogue with a rich and multifaceted discursive tradition of cannibalism in modern, and premodern, China. And, second, cannibalism itself occupies a rather curious position in our own (Western) cultural imagination, and the challenge of how to read cannibalism cross-culturally has important implications for the broader question of what is at stake, and at risk, in cross-cultural reading and criticism in general.

- Cannibalism is a curious thing. In modern Western culture, cannibalism enjoys a virtually unparalleled hold on the popular imagination as an act of primal social violence. It is frequently held up as an almost unthinkable transgression of the social and moral codes which make us who we are.[1] At the same time, however, this nearly unthinkable act has consistently, and somewhat paradoxically, proved to be all-too-thinkable, as evidenced both by the abundance of cultural representations of cannibalism which exist in our "own" culture, together with the voyeuristic fascination occasioned by the prospect of cannibalistic practice among primitives, deviants, etc., in "other" cultures.[2] Discourses and fantasies of cannibalism, therefore, occupy a crucial liminal space where the presumptive limits of human society are simultaneously challenged and implicitly reaffirmed.[3]

- Taking the Taiwan restaurant rumors as my starting point, in this essay I will elaborate a selective discursive genealogy of representations of cannibalism in twentieth-century Chinese culture. Specifically, I will consider four such cases, together with the cultural and social contexts in which they are embedded. In this survey, my intention is not to focus on the literal, physical act of cannibalism, but rather to use the discursive tradition of cannibalism as a prism through which to reflect on the processes of identification and differentiation by which not only the Self but also an array of social collectivities are constituted. Rather than being derived from explicit, manifest criteria, these psychic, social, and epistemological constructs are, instead, the result of complex flows of equivalence and alterity, and often it is, ironically, precisely at the closest points of identification that the most systematic patterns of social rupture are produced.

- My discussion of cannibalism will be conducted at two levels. On the one hand, I will seek to consider the significance of each instance of discursive cannibalism in its respective context, noting the way in which each elaboration builds, in part, on a shared discourse of cannibalistic allusions. On the other hand, I will seek to generalize from these specific instances of cannibalism and encorporation and use them as an abstract model for the reading process itself. Finally, at the end of the essay, I will seek to bring these two dimensions of cannibalism (contextualized specificity and abstract model, respectively) together, to consider the hermeneutic ethics of the act of reading cannibalism itself in a cross-cultural context. In particular, I will suggest that these actual discourses of cannibalism constitute an important challenge to how we approach the possibility of cross-cultural reading and perception, even as the abstract trope of cannibalism may itself provide a useful model for better understanding the hermeneutic ethics of cross-cultural reading and perception itself.

- The Taiwanese restaurant cited in the Malaysian tabloid article had not, it turns out, done anything out of the ordinary, though the images which accompanied the article were themselves not without a basis in reality. Specifically, the photos were taken as part of a performance entitled "Eating People" (or "Man-Eater") [shiren] performed on 17 October 2000 in Shanghai by the 30-year-old avant-garde performance artist Zhu Yu (see Figure 1). One widely publicized report quotes Zhu as saying that "to create Man-eater, he said he cooked the corpses of babies that had been stolen from a medical school. Zhu admitted that the meat obtained from the bodies tasted bad, and said he had vomited several times while eating it. However, he said, he had to do it 'for art's sake'" ("Baby-Eating").

-

In public comments he made at the time of the performance, Zhu Yu sought

to address the significance of the scandalous nature of the his act, while

at the same time attempting to relativize the social and cultural

assumptions which make it appear scandalous in the first place:

One question that always stymies us--that is, why cannot people eat people?

Is there a commandment in man's religion in which it is written that we cannot eat people? In what country is there a law against eating people? It's simply morality. But, what is morality? Isn't morality simply something that man whimsically changes from time to time based on his/her own so-called needs of human being in the course of human progress.

From this we might thus conclude:

So long as it can be done in a way that does not commit a crime, eating people is not forbidden by any of man or societies laws or religions; I herewith announce my intention and my aim to eat people as a protest against mankind's moral idea that he/she cannot eat people. (qtd. in Hua 192) - Here, Zhu Yu draws attention to cannibalism's peculiar position at the center of contemporary society's own self-conception, while also foregrounding its status as being effectively outside the purview of secular authority. Like the proverbial incest taboo, cannibalism is often viewed as a foundational prohibition on which the social order is grounded, but which, at the same time, derives significance precisely through its own potential transgression. The prohibitions against incest and cannibalism are both examples of socio-cultural taboos which, by their very ostensible universality, bring into question the ontological status of the categories of cultural identity within which they are imbedded. Furthermore, it is not coincidental that both prohibitions are explicitly concerned with negotiations of identity and contestations of equivalence. René Girard, for instance, includes both incest and cannibalism under the master category of sacrificial violence, speculating that "We are perhaps more distracted by incest than by cannibalism, but only because cannibalism has not yet found its Freud and been promoted to the status of a major contemporary myth" (276-77).

- Despite the universalizing tenor of Zhu Yu's own remarks, his "Man-Eater" performance quickly became mired in a rather mundane debate over cultural and social differences. For instance, by mid-July of 2001, the R.O.C. [Taiwan] Government Information Office [GIO] had sprung into action, repeating the explanation that the story and the photographs were actually derived from Mainlander Zhu Yu's October performance the preceding year, rather than from any culinary malfeasance on the part of the Taiwanese restaurant, and concluded cheerfully that "the GIO wishes to emphasize that no event of this kind has ever taken place in Taiwan, and that the serving or eating of such a dish would break an ROC law against the defiling of human corpses" (Republic). With this rhetorical flourish, the GIO report succeeded in taking a debate which might have appeared to center on cultural universals concerning the sanctity of the human body and adeptly translated it into a rather more provincial debate over regional mores and secular authority.[4]

- In this way, the debate provides a prism into how various Chinese communities attempt to portray themselves and each other under the eyes of a globalized public. Aihwa Ong has proposed the notion of "flexible citizenship" to describe the processes by which "refugees and business migrants" (in her study, specifically Sino-Asian ones) negotiate affiliations and loyalties to multiple nation-states (often investing and working in one or more countries, while keeping their families in another). She argues that these forces of transnational migration have had the effect not only of encouraging these migrant businessmen to rethink their symbolic location within an increasingly complex web of ethnic and national alliances and rivalries (she cites, for instance, the example of how a "triumphant 'Chinese capitalism' has induced long-assimilated Thai and Indonesian subjects to reclaim their 'ethnic-Chinese' status" [7]), but also, at the same time, producing important "mutations in the ways in which localized political and social organizations set the terms and are constitutive of a domain of social existence" (215). Speaking metaphorically, therefore, we might conclude that what each of these interventions (by Zhu Yu himself, the Malaysian newspaper, the Taiwan GIO, the overseas Chinese e-mail communities, etc.) have in common is that they each ironically take the same alleged act of cannibalism and use it is as a pretext to begin cannibalistically feeding on each other on a global stage, as they try to negotiate the competing imperatives of a localized, "national" locus of identity on the one hand and of an increasingly fluid, transnational network of ethnic alliances and identifications on the other.

- Though unquestionably shocking in and of itself, Zhu Yu's October 17th, 2000 performance was by no means an anomaly when viewed in the context of his own recent corpus of work or that of the larger community of iconoclastic young artists with whom he is frequently associated. To understand the social and cultural context in which these artists were working, however, it is necessary to backtrack briefly. During the first couple of decades following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, and particularly during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), cultural production in Mainland China was tightly controlled. After the death of Chairman Mao and the official end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, Chinese artists began to have a somewhat freer rein to express themselves, and some chose to develop in an experimental, avant-garde direction. These trends in experimental art have became increasingly pronounced during the 1990s, following the 1989 Tiananmen "democracy" protests and the subsequent military crackdown.

- Art historian Wu Hung has identified four general historical phases or "generations" in post-Cultural Revolution experimental art, beginning with the initial emergence of Chinese experimental art between 1979 and 1984: the "'85 Art New Wave Movement" (1985-1989); the internationalization of experimental art (1990-93); and the "domestic turn--art as social and political critique" (1994-present) (Transience 16). Within each of these broad generational groupings, however, the artists and their works generally span the spectrum from committed political protest to a cynical cultivation of foreign capital (and of the attendant Western fetishization of Oriental exotica). While initially much of this experimental art was primarily a response to the historical trauma of the Cultural Revolution, an important theme which began to emerge in the mid-1980s was that of a response to, and commentary on, the rapid economic development under Deng Xiaoping. The ideological vacuum created in the wake of the death of Mao and the end of the Cultural Revolution, combined with the widespread interest in getting rich, led to a brief period of "Nietzsche fever" in the late 1980s, with his motto "god is dead" being perceived as having particular relevance to China's current condition.[5]

- Having mostly emerged onto the art scene in the mid- to late 1990s, Zhu Yu and his colleagues could generally be placed in this fourth generation. No longer responding directly to the Cultural Revolution (as was initially the case with many of their older colleagues), they see themselves as trying to push the envelope of artistic acceptability, while at the same time remaining keenly aware of the interest taken in their work by foreign academics and curators. Many of the artists in Zhu Yu's immediate circle are best known for what can be seen as a combination of installment and performance art, often using their own bodies as well as human and animal flesh in elaborately choreographed performances. They tend to work on the margins of official permissibility, with their "closed-door" performances generally well-publicized (though often at the last minute), but usually not "officially" open to the public.

- Zhu Yu's "Eating People" performance itself was reportedly part of a series of exhibitions entitled "Obsession with Injury" [dui shanghai de milian].[6] Part of a larger phenomenon of "shock-art" in contemporary China, this provocative series of avant-garde performances used not only animal and human corpses, but also the bodies of the artists themselves, in order to challenge conventional assumptions about the limits of both human and social mortality. As the artists themselves describe their project: "We have always wanted to explore fundamental problems concerning the existence and death of human beings, as well as the transformative process of spirit into material" (Wu, Exhibiting 207).

- For instance, the second, closed-door installment of the "Obsession with Injury" series, held on 22 April 2000, featured a performance in which Zhu Yu himself "had cut a piece of skin from his own body and sewn it onto a large piece of pork. A photo on the wall showed him in the middle of surgery; a videotape showed the process of the operation" (Hua 190-91; Wu, Exhibiting 206). In another performance, the artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu sat in adjacent chairs as nurses transfused their own blood into the preserved corpses of a pair of infant Siamese twins (Hua 98; Wu, Exhibiting 204). Peng Yu also participated in another performance which consisted of "dropping oil extracted from human fat into the mouth of a medical specimen of a child's corpse," with this latter performance also incorporating a video of the oil-extraction. All three of these performances shared a common concern with challenging conventional boundaries between human and animal, between living flesh and preserved corpses, as well as the boundaries between reality and electronic simulation (in their integration of live performances and videotaped reproductions).

- The performances in this "Obsession with Injury" exhibition, and others like it, collectively sought to bring a fresh perspective to conventional assumptions about the status of human corporality. While it has become commonplace, within the experimental trends in Chinese literature and art, to feature representations of acts of extreme violence being performed on the human body (consider, for instance, Tang Yuanbao's act of peeling off the skin of his own face at the end of Wang Shuo's novel Please Don't Call Me Human), what is remarkable about the "Obsession" performances is their use of actual human flesh (both from the artists' own bodies, as well as that of preserved human corpses).

-

The use of human and animal flesh was clearly a striking component of these sorts

of exhibits, to the point that contemporary critics speak in general terms of the

fascination with "meat art" in contemporary Chinese avant-garde art. At the same

time, however, the artists, in their discussions of their work, repeatedly tried

to downplay the significance of their use of this "meat." For instance, at one

point they explain that,

First of all, we did not use corpses in a conventional sense, because all of the human bodies we employed were specimens that had been medically treated. Their cells had been conditioned by formaldehyde and could no longer rot or be infected by germs. These so-called bodies are germ-free and had already been turned into chemical substances. (Wu, Exhibiting 206)

- These comments are almost as startling as the performances to which they refer. While on the surface appearing to undercut the transgressive implications of their performances which appear to center around the deliberate desecration of human bodies (claiming, in effect, that they are not actual human bodies which they are using), these comments actually raise a host of potentially even more problematic questions concerning the limits of "human" mortality and human corporeality. Particularly interesting is the implication that infectious "germs," typically viewed as contaminants, are actually part of what makes the bodies "human" in the first place.

-

Furthermore, even as these "shock-artists" were capitalizing on the referential

presence of their subject matter (be it actually "human" or otherwise), they were

at the same time struggling to get beyond the purely material dimension of their

performances. As Zhu Yu explained in a later interview:

Our intention was not to use these materials to say something. We want our works to say something. But right now, the audience doesn't have the ability to accept something like this is. People haven't seen this kind of an exhibition before, where real things are used. The audience is reacting to the materials. After seeing it more times, then maybe they will be able to see what's inside of these works. [...] The result is already pre-determined because these materials, from a certain perspective[,] are concepts in themselves. So it's easy for the audience to think purely about the materials when they see these works. From another perspective, the materials are an obstacle for us. (Wang, "Sadistic")

- These comments take one of the central issues of the later cannibalism debate and turn it back upon itself. That is to say, one of the key themes in the various discussions of the cannibalism allegations was one of reference or denotation: to what extent did the photographs constitute mere visual simulacra, or to what extent could they be taken as a standing in an indexical relationship with an outer reality?

- Moreover, even after it was revealed that the controversial photographs were actually derived from Zhu Yu's performance in Shanghai, questions still remained for some viewers over what precisely that performance consisted of: was it actual cannibalism, or not? Was it a cannibalistic act that was being presented as a work of art, or was it instead an elaborate mock-up intended to mimic an act of consuming actual human flesh? Similarly, in the "Obsession with Injury" performances, the question ultimately becomes not simply that of the reliability of the various visual reproductions being used, but also, and even more importantly, that of the referential status of the human body itself. The human body is, in a sense, being subjected here to a chiasmatic conjunction of mutually opposed hermeneutic imperatives. On the one hand, the medical specimens are being effectively evacuated of their conventional connotations, becoming essentially empty shells of their former selves. At the same time, however, these newly sterilized bodies are then remobilized as potent cultural signifiers, connoting the bodily fragility to which their own transformation itself stands as an eloquent testament.

-

Zhu Yu's and his colleagues' "shock art" appears to challenge conventions

of human morality and propriety, even as it pushes the envelope of acceptable

artistic expression. Building, in part, on contemporary Chinese youths'

perception that they lack an effective public forum in which to express their

views and concerns, these sorts of sensational performances effectively transform

the human body into a textually inscribable medium. Living in a post-Maoist

social ethos commonly described as lacking a coherent moral center, these young

artists rely on the deliberate transgression of some of society's most

deeply ingrained cultural prohibitions in order to make socially meaningful

statements.

Eat thy Neighbor

As iconoclastic as it might seem at first glance, Zhu Yu's cannibalistic performance was also implicitly in dialogue with a variety of other contemporary and historical discourses of cannibalism in Chinese culture. Some of the most recent such examples include Scarlet Memorial: Tales of Cannibalism in Modern China, Zheng Yi's exposé on the cannibalism practiced during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), as well as Yu Hua's provocative 1980s short story "Classical Love," in which an errant wanderer falls in love with a beautiful maiden at a remote inn, who is ultimately killed and dismembered for her meat. More abstract, but equally graphic, is the Hong Kong director Siu-Tung Ching's popular 1988 film, A Chinese Ghost Story, which revolves around a graphic theme of vampiric cannibalism, with the hermaphroditic tree-spirit "Laolao's" preposterously oversized tongue snaking through the half-real/half-fantasy space of this epistemological hinterland.Since it is possible to "exchange sons to eat," then anything can be exchanged, anyone can be eaten.

Lu Xun, "Diary of a Madman"

- Probably the more famous evocation of cannibalism in modern Chinese literature, however, is Lu Xun's celebrated 1918 short story, "Diary of a Madman," in which a Gogolesque paranoiac becomes convinced that his neighbors, and even his immediate relatives, are all scheming to eat his flesh. The story concludes with the narrator's conviction that he, too, has unwittingly consumed human flesh, and as a result will himself become a cannibal, yet still holds out hope that "the children" may somehow be saved from this vicious cycle of self-consumption: "Perhaps there are still children who have not yet eaten men. Save the children...." (18).

- Lu Xun's story is typically read as an allegorical excoriation of the "cannibalistic" society which China had become--one in which people feed off of each other's weaknesses, rather than rallying together to a common cause. The work itself is also generally held up as marking the symbolic birth of a Chinese literary modernism, in that it not only constitutes an allegorical critique of the old society, but furthermore is itself one of the earliest works to be written in the modern vernacular.

- Lu Xun himself is generally recognized as one of the leading figures of the reformist May Fourth Movement of the late 1910s and 1920s. Following on the heels of the 1911 fall of China's last official dynasty, the Qing, the May Fourth Movement was generally concerned with attempting to strengthen the Chinese nation by both introducing into China a variety of foreign (primarily Western) social ideas, scientific paradigms, and aesthetic trends, as well as identifying and critiquing those "traditional" tendencies in Chinese society which were perceived as being responsible for its weakness and inability to "modernize" effectively. Historian Lin Yü-sheng identifies the May Fourth Movement's general attitude as being one of "totalistic anti-traditionalism": an ostensible wholesale rejection of the social and ideological legacies of the past, which at the same time has the ironic effect of partially obscuring the degree to which the reformists were themselves building pre-existing models of literati involvement and social critique.

- "Diary of a Madman" is the first of the socially motivated stories which Lu Xun wrote during this May Fourth period, but its metaphor of cannibalism is one to which he would return in several of his subsequent writings (as, for instance, with the blood-soaked mantou bun which is presented, in his story "Medicine," as an unsuccessful cure for tuberculosis), and which many other authors would later pick up on and develop in their own right. At the same time, however, the signifier of cannibalism in Lu Xun's work is a richly overdetermined one, in the sense that it inevitably exceeds the straightforward allegorical reading outlined above. Cannibalism is an abstract symbol in the story, but is also a symbol which builds in part on allusions to actual historical accounts of cannibalism. Part of the narrator's horror is precipitated by his gradual realization that many of the references to cannibalism in familiar historical texts, ranging from the fourth-century B. C. E. Warring States period to the sixteenth-century Ming dynasty, might actually be literal references, rather than mere rhetorical expressions. Therefore, the subtext of the story becomes not only one of critiquing contemporary societal conditions, but also one of distinguishing between empty signifiers and actual historical referents. In short, it becomes a question of how to read, how to make sense of the literal or figurative dimensions of familiar historical texts.

-

At another point in the story, Lu Xun relates how the narrator stayed up late one

night rereading the canonical dynastic histories, which were filled on every page

with allusions to the Confucian ideals of "Virtue and Morality." The madman is

then described as having an epiphany, whereby he suddenly becomes able to

read through the surface meaning of the texts and discern their

implicit, underlying meaning:

"Cannibalism," here, becomes not only a trope for a kind of clarity of social vision, an ability to perceive the involutive and self-destructive tendencies of contemporary Chinese society, but also a figure for a certain kind of hermeneutics, an ability to read a (historical) text against itself. What is at stake is not merely a simple dialectics between surface visibility and hidden meaning, but rather the ability to recognize the (potential) meaning in what was (always) already "visible" in the first place.Everything requires careful consideration if one is to understand it. In ancient times, as I recollect, people often ate human beings, but I am rather hazy about it. I tried to look this up, but my history has no chronology, and scrawled all over each page are the words: "Virtue and Morality." Since I could not sleep anyway, I read intently half the night until I began to see the words between the lines. The whole book was filled with the two words--"Eat people." (10)

- Lu Xun died somewhat prematurely in 1936, at the age of 55. Although he was actively involved with the League of Left-Wing Writers during the last decade or so of his life, he made a point of never formally joining the Chinese Communist Party. Chairman Mao Zedong nevertheless subsequently lauded Lu Xun as "the major leader in the Chinese cultural revolution. He was not only a great writer, but also a great thinker and a great revolutionary" (372). In spite of this unconditional accolade, it nevertheless remains very questionable to what extent the acerbically critical Lu Xun would have approved of the subsequent Maoist regime. Nevertheless, under the P.R.C. Lu Xun was elevated to the pinnacle of the Chinese literary canon (thanks, in no small part, to Mao's own unreserved endorsement of Lu Xun's revolutionary credentials). Speaking metaphorically, therefore, we could say that his writings and legacy were subsequently consumed and incorporated by the Maoist socio-political orthodoxy, as, for instance, in the case of his celebrated condemnation of the "human-eating old society," which ultimately became monumentalized within the post-1949 ideological rhetoric of the Chinese Communist Party. At the same time, this rhetorical incorporation on the part of the Party also involves an important process of misreading, an attempt cannibalistically to make a part of itself a position of ideological critique which, otherwise, might have potentially constituted one of its strongest challenges.

- I would take this conclusion and carry it a step further, arguing that the problematic posed by cannibalism (under this latter, more abstract understanding of the concept) is not only one of reading history, or of reading historically, but rather it is one of "reading" in general. The physical act of cannibalism is only meaningful when positioned at the interstices of identity and alterity (in that it is an act of consuming the non-Self with whom one has strong, categorical ties), and is grounded on the ways in which we make sense of the complex social tapestry which the cannibalistic act itself simultaneously negates and reaffirms. Furthermore, the act of cannibalism is itself grounded on a complex hermeneutics of identity, of how we understand and imagine our relationship with a variety of social Others. In the following section, I will pursue this reading to its logical conclusion, looking not at the consumption, but rather at the constitution of human flesh, and the way in which the human body itself has been imagined as a complex mass of incommensurable elements, lacking a preconceived identity, and instead actively constituted through the immune system's continual hermeneutic process of "reading" patterns of identity and alterity.

-

Devouring Oneself from Within

Lu Xun's allegorical encounters with cannibalism mark an important turning point in his own intellectual development. It is well known that Lu Xun initially studied medicine in Japan, and that he later claimed that it was the perceived need to get to the root of the spiritual and social ills which afflicted contemporary China which led him to abandon his medical studies and instead devote himself to healing not the bodies of his compatriots but rather their spirits. His critical description of China as a cannibalistic society in "Diary of a Madman" became one of the rallying points of his generation and has continued to echo throughout the twentieth century. At the same time, even as his earlier interest in corporal healing was effectively sublimated, that same medicinal orientation was making an uncanny return in many of his later writings, as well as those of his contemporaries.Pre-eminently a twentieth-century object, the immune system is a map drawn to guide recognition and misrecognition of self and other in the dialectics of Western biopolitics.

Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women

- For instance, in an essay entitled "Random Thoughts #38" and published under Lu Xun's name in 1918,[7] the same year of "Diary of a Madman," there is an explicit parallel drawn between the contagion of the human bloodstream by syphilis bacteria and the ideological "confusion" of the social corpus resulting from the influence of "Confucians, Taoists, and Buddhist monks": "Even though we might now want to become real people, it is uncertain whether or not we will [be able to avoid being] confounded by the dark and confused elements in our blood-stream" (389). The essay expresses concern, furthermore, that this ideological disease not reach the nadir of syphilis and concludes with the hope that science may discover some magic cultural/ideological panacea, a so-called "707," based on the recently discovered treatment for syphilis (arsphenamine, conventionally known at the time as "606"). The image of harmful reactionary ideological elements flowing through society's bloodstream is evocative in and of itself, but the specific allusion to syphilis makes the metaphor even more compelling, in that the tissue damage from syphilis results, at least in part, from white blood cells' attacking previously healthy tissue. The result is a cannibalistic extravaganza ironically reminiscent of "The Diary of a Madman" from a few months earlier.

- While the connection between the immune system and "cannibalism" is admittedly somewhat indirect in this 1918 essay, it is nevertheless developed much more explicitly in several other reformist essays published during the same general period. In the following discussion, I will consider three of these essays, all of which were published between 1915 and 1918 in the same journal, New Youth, which also published not only "Diary of a Madman" but also the 1918 "Random Thoughts" essay as well. In particular, I will focus on the ways in which each of these essays develops an increasingly elaborate double metaphor, whereby the metaphoric "cannibalism" on the part of the immune system's white blood cells itself becomes a model for the ways in which different elements within Chinese society feed upon each other.

-

The first of these essays appeared in the 1915 inaugural issue of New

Youth. There, the editor of the journal, Chen Duxiu, published an

influential article entitled "Call to Youth," where he explicitly elaborates a

metaphorical correspondence between individuals in society and cells in the human

body:

In this essay, the references to metabolic processes and cell replenishment represent an interesting synthesis of Western medical metaphors, on the one hand, and of the longstanding tradition, in Chinese writings, of elaborating metaphorical parallels between the human body and the social "body politic," on the other.[8]Youth have the same relationship to society that the new and lively cells have with respect to the human body. In the metabolic process, the old and rotten cells are constantly being weeded out, and openings are thus created which are promptly filled with fresh and lively cells. If this metabolic process functions correctly, the organism will be healthy; but if the old and rotten cells are allowed to accumulate, however, the organism will die. If this metabolic process functions properly at a social level, society will flourish; but if the old and corrupt elements are allowed to accumulate, society will be destroyed. (Chen 1)

- The biomedical underpinning of the corporal metaphor is elaborated in more detail in "The Thought of Two Modern Scientists," an essay Chen Duxiu wrote the following year, on the occasion of the death of Russian biologist Elie Metchnikoff (1843[5?]-1916). In the second section of this essay, Chen addresses Metchnikoff's work and its relevance to human longevity.[9] In particular, he stresses Metchnikoff's discovery of the significance of white blood cells in the immune system, and specifically their ability to engulf and absorb harmful microbes. To describe these white blood cells, Metchnikoff coined the term "phagocyte," derived from Greek terms "phago" ("to eat") and "kyto" ("tool"), and which Chen translated into Chinese as "shijun xibao," or "bacterium-eating cell." The obvious question to ask next, Chen writes, is whether the white blood cells can be seen as acting out of a sense of duty to the larger body, or whether they are simply pursuing a narrow course of individual self-interest. The answer is clear, he writes in response to his own rhetorical question: they are simply acting in their own self-interest, to feed themselves. This explains the apparent paradox which Metchnikoff observes, whereby as the body ages and loses its vigor, the white blood cells, by contrast, may become overly active, attacking elements of the body itself (from the nervous system to the cells responsible for hair pigment), "mistakenly" regarding them as foreign pathogens. After a further discussion of the role played by intestinal bacteria in the aging process, Chen concludes that once a way is found to control (or even eliminate) these "cannibalistic" white blood cells, it may be possible to extend human longevitty by a century or more (49).

-

More than the specifically medical implications of Metchnikoff's model, Chen was

apparently fascinated by the question of the social implications which this model

of phagocytes and their relationship to the larger body (politic), and of how

they might enable us to rethink the relationship between "altruism" and

"individualism." Chen concludes the essay by applying some of these same

questions of altruism vs. individualism to his Metchnikoff himself:

What we see here, therefore, is Chen's attempt to use biological metaphors to provide a model for a position of constructive social criticism, one which avoids the dual dangers of self-effacing conformism and "altruism," on the one hand, as well as that of "absolute individualism" (e.g., the white blood cells which destroy the body itself), on the other.Although Metchnikoff advocates individualism, nonetheless the principles by which he lived out his life were definitely not ones of absolute individualism. Although he did not take benevolence and altruism to be ultimate ends, his actions were nonetheless compatible with these general principles (51).

-

In 1918 fellow reformist Hu Shi developed this same immune system

metaphor in the lead article of a New Youth special issue on Ibsen.

Hu Shi concludes the article with a medical metaphor inspired by the figure of

Dr. Stockman in Ibsen's play, "Enemy of the People":

When we read this essay in conjunction with Chen's original 1915 one, we realize that what is implied is that the "evil and filthy elements in society" are actually not foreign pathogens, but rather they are none other than the same "old and rotten" cells from the body itself. Therefore, in this essay--almost precisely contemporaneous with Lu Xun's identification, in "Diary of a Madman," of cannibalism as the metaphorical condition from which society must attempt to extricate itself--we here have instead an implicit argument in support of figurative cannibalism, a call for social "white blood cells" to seek out and consume "the evil and filthy elements in society." An act of collective self-awakening, therefore, implies a process of self-alienation, a systematic identification and excision of unprogressive elements.It is as if [Ibsen] were saying, "People's bodies all rely on the innumerable white blood cells in their bloodstream to be perpetually battling the harmful microbes that enter the body, and to make certain that they are all completely eliminated. Only then can the body be healthy and the spirit complete." The health of the society and of the nation depend completely on these white blood cells, which are never satisfied, never content, and at every moment are battling the evil and the filthy elements in society, and only then can there be hope for social improvement and advancement. (Hu 20)

- While Lu Xun, Hu Shi, and Chen Duxiu were all leading members of the May Fourth Movement, they nevertheless all occupied quite distinct positions within Chinese ideology and politics. Chen Duxiu was one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party, while Lu Xun made a point of never joining the party, though he worked closely with several Party leaders during the 1920s and 1930s. Hu Shi, meanwhile, ended up siding with the Kuomingtang and consequently has been generally reviled in much Mainland historiography.[10] Despite these manifest differences in their political and aesthetic orientations, it is nevertheless striking that they have each come together on this same medico-political metaphor of the cannibalistic white blood cells. Somewhat independently of the meaning which they each originally might have intended the metaphor to convey, this metaphor itself can nevertheless be read deconstructively, suggesting a body at war with itself, but the underlying implication being that this condition is, in fact, part of the status quo. Young and lively cells must, for the benefit of the whole, seek to eliminate and replace old and tired ones. The boundary between productive regeneration and cannibalistic self-consumption, therefore, is an exceedingly tenuous one, largely contingent on the speaker's relationship with the elements which are doing the "consuming."

- The irony inherent in these various white blood cell metaphors is that while Metchnikoff originally suggested that the elimination of these cells would, in effect, forestall the aging process, in the metaphorical formulations of many of these May Fourth reformers, the white blood cells' ability to feed on ossified portions of the social Self becomes an asset, rather than a liability. Hu Shi and company are, in effect, arguing that we must combat social cannibalism with cannibalism, devouring those reactionary elements of society before they can succeed in devouring us.

- These sorts of physiological metaphors represent a chiasmatic intersection of objectivity and fantasy. They draw on an increasingly detailed medical understanding of the structure and function of the human immune system, while at the same time reducing the imaginary space of the nation to a highly metaphoric plane. The increased precision with which the function and behavior of these white blood cells is described goes hand-in-hand with an increased degree of abstraction in the description of human behavior.

- Furthermore, it is highly appropriate that it was specifically the immune system which provided the May-Fourth-period reformers with one of their favorite models in this struggle to define themselves through the mediated gaze of the other, appropriate in that the immune system is itself essentially a machine of self-recognition and self-reproduction, one which functions by reducing processes of identification to the barest heuristic strategies. In fact, the immune system can even be seen as a quintessential sublimation of the process of self-identification, whereby the process of "identification" operates essentially independently of the "self" which it ostensibly presupposes. Accordingly, the immune-system metaphor provides an ironically apt model of a "pure" form of cannibalism, as well as an illustration of its theoretical limits. In the case of the immune system, relations of identity and alterity are explicitly created in the process of recognition itself.

- The coherence of the organism, therefore, is itself premised on a continual struggle of identity politics at the cellular level. Phagocytotic consumption on the part of white blood cells represents a conceptual limit-point for our understanding of cannibalism--it is, in a sense, not "true" cannibalism, because the cells only devour that which they recognize as "Other." At the same time, however, the functioning of these cells illustrates the degree to which these categories of Self and Other are never a priori givens, but rather are themselves the product of metaphorical processes of reading itself.

-

In a critical overview of more recent Western medical models of the immune

system, feminist theorist Donna Haraway suggests that these models come to assume

a notion of "identity" as merely an amorphous, decentered play of difference:

"In a word, no," she writes, in reply to her own rhetorical question. The notions of "self" presupposed by these immune system models are, instead, continually contested and always already "under erasure." While Haraway posits that this deconstructive turn in immune system models represents a specifically "post-modern," late-twentieth-century development, my reading of these May-Fourth-period texts suggests that many of these deconstructive implications were latently present in the model all along.Does the immune system--the fluid, dispersed, networking techno-organic-textual-mythic system that ties together the more stodgy and localized centers of the body through its acts of recognition--represent the ultimate sign of altruistic evolution towards wholeness, in the form of the means of co-ordination of a coherent self? (219)

- The "Western" medical and hygienic perspectives being introduced into China during the May Fourth era contributed to a number of radical shifts in the understanding of the constitution of not only the human body itself, but also the social communities and societies which these bodies inhabit. One of the more prominent examples of Chinese incorporation of Western medical knowledge is that of these immunological models of social organization. Ironically, however, one of the implications of these immunological models, as they were developed in the May Fourth era, involves precisely a recognition of the inherent contingency of the processes by which corporal or social bodies are differentiated from "foreign" elements. That is to say, the act of incorporating "Other" (Western) models ironically resulted in an implicit rethinking of the conceptual basis upon which the boundaries between "Self" and "Other" are constructed in the first place.

-

Journeys into the Interior

The preceding May Fourth-era explorations into "cannibalistic" practices deep within the human body are ironically mirrored by the allegorical investigation of cannibalistic allegations deep within China's own geographic interior in the 1993 novel The Republic of Wine by one of contemporary China's most pre-eminent writers, Mo Yan. Born into a peasant family in 1955 and raised in rural Northern China, Mo Yan began publishing short stories and novels in the mid-1980s. Though he is sometimes grouped with the experimental writers who came of age in the 1980s (including figures such as Yu Hua, Ge Fei, Can Xue, etc.), Mo Yan's early fiction tends to emphasize conventional storytelling and rural subject matter more than these other authors, and as such would be more accurately categorized as a "native soil" author. The events associated with the 4 June 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square appear to have had a significant influence on him, and it was in the latter part of that year that Mo Yan began writing The Republic of Wine, which perhaps still stands as his most innovative and unconventional work to date--whereby the social violence of the Tiananmen military crackdown would almost appear to have been displaced onto the narrative structure of the novel itself.Mo Yan Sir Mo Yan Sir what's wrong please wake up This guy wrote Red Sorghum but he's a fledgling with alcohol can't hold his liquor but comes to Liquorland to stir up trouble take him to the hospital bring a car over first give him some carp broth to sober him up carp promotes lactation don't tell me he just had a baby a meat boy set it in a big gilded platter [...]

Mo Yan, The Republic of Wine

- Mo Yan is probably best known for his 1986 novel Red Sorghum, on which the renowned fifth-generation director Zhang Yimou based his directorial debut the following year. The earlier work opens with the evocative epigraph, "[...] As your unfilial son, I am prepared to carve out my heart, marinate it in sauce, have it minced and placed in three bowls, and lay it out as an offering in a field of sorghum"; and acts of symbolic cannibalism similarly lie at the heart of the work itself. For example, the secret recipe of the novel's trademark wine is that it is fermented with human urine. Furthermore, later in the novel, there is an extended description of how, during the Chinese civil war, previously domesticated dogs gone wild feed on the decaying flesh of the human corpses which litter the landscape, and how the protagonists themselves have no other recourse but to feed on this dog flesh, flesh which is only one step away from their own. In this way, the canine-mediated cannibalism becomes a powerful metaphor for the internecine warfare in which China found itself in the 1940s following the withdrawal of the Japanese troops.

- The Republic of Wine, which Mo Yan began to write roughly three years later, builds quite directly on the thematic precedent set by Red Sorghum--literalizing Red Sorghum's attention to bacchanalian excess and cannibalistic transgression, even as it transposes the earlier novel's concerns onto a more self-consciously fictional plane. The Republic of Wine constitutes not only a journey into the fictional space of China's interior hinterland, but furthermore can also be seen as a figurative journey back into China's own literary history of cannibalistic metaphors. For instance, it tropes quite explicitly on one of China's greatest travel narratives: the fifteenth-century novel Journey to the West, whose own assorted allusions to cannibalistic practice constitute part of the cultural background of Mo Yan's development of the topic.[11] Furthermore, The Republic of Wine's attention to the theme of child cannibalism inevitably finds itself in dialogue with Lu Xun's own classic short story on the topic, with Mo Yan's novel alluding repeatedly to Lu Xun as an ironic avatar of literary canonicity.

-

The basic premise of the main The Republic of Wine narrative

concerns a hapless government investigator by the name of Ding Gou'er, who has

been sent to a fictional province deep in the Chinese interior to investigate

allegations of cannibalism, and specifically the consumption of human infants.

When he finally arrives at this "Liquorland," his hosts treat him to a decadent

banquet, the pièce-de-résistance of which is a dish

consisting of a human boy prepared whole and roasted to a deep shade of brown:

The boy sat cross-legged in the middle of the gilded platter, golden brown and oozing sweet-smelling oil, a giddy smile frozen on his face. Lovely, naïve. Around him was spread a garland of green vegetable leaves and bright red radish blossoms. The stupefied investigator swallowed back the juices that rumbled up from his stomach as he gawked at the boy. A pair of limpid eyes gazed back at him, steam puffed out of the boy's nostrils, and the lips quivered as if he were about to speak. (75)

-

Upon seeing this culinary confirmation of his darkest suspicions, Ding

Gou'er--who, by this point, is rather drunk--immediately attempts to

arrest his hosts for practicing cannibalism. His hosts, however,

patiently explain to him that it has all been a misunderstanding, and that

the dish in question is actually merely an elaborate culinary simulacrum,

carefully designed to mimic the shape and texture of a human infant, while

in fact consisting only of mundane comestibles:

What began as a scandal of cannibalism thus becomes, instead, a postmodern scandal of representation and reference; and as the novel progresses, it remains ambiguous (and ultimately irrelevant) whether that which the inebriated Ding Gou'er witnessed was an actual human infant, or merely a culinary facsimile of one. Furthermore, this radical skepticism towards the boundary between reality and representation, referent and simulacrum, in turn comes to feed parasitically on the plot of the actual novel itself, causing it to fold back upon itself, as a spectral apparition of the author himself ends up falling into the fictional abyss of the novel that he is attempting to write. To understand what is meant by this, however, it will be necessary to return briefly to a description of the structure and contents of the novel."Old Ding, good old Ding, you're a fine comrade with a strong humanistic bent, for which I respect you," Diamond Jin said. "But you're wrong. You've made a subjective error. Look closely. Is that a little boy?" His words had the desired effect on Ding Gou'er, who turned to look at the boy on the platter. He was still smiling, his lips parted slightly, as if he were about to speak. "He's incredibly lifelike!" Ding Gou'er said loudly. "Right, lifelike," Diamond Jin repeated. "And why is this fake child so lifelike? Because the chefs here in Liquorland are extraordinarily talented, uncanny masters." The Party Secretary and Mine Director echoed his praise: "And this isn't the best that we have to offer! A professor at the Culinary Academy can make them so that even the eyelashes flutter. No one dares let his chopsticks touch one of hers." (77)

- The core The Republic of Wine narrative, as summarized above, is embedded within an outer narrative frame, in which a fictional "Mo Yan" (appearing as a character within his own novel) is portrayed as trying to complete the Republic manuscript. A central premise of this outer narrative frame is that the fictional "Mo Yan" finds himself in the position of being a reluctant cultural icon idolized by enthusiastic fans of Red Sorghum, and in particular by a certain Li Yidou, a Ph.D. candidate in liquor studies at the Brewer's College in Liquorland, whose passion for wine is rivaled only by his morbid fascination with cannibalism and other dark recesses of the human soul. In this outer frame of the novel, the fictional "Mo Yan" is in the process of writing the The Republic of Wine narrative itself, even as he finds himself in epistolary dialogue with Li Yidou, who asks "Mo Yan" to use his institutional connections to help him gain a foothold within the publishing industry. Accordingly, Li Yidou sends "Mo Yan" a series of short stories, each more outlandish than the last, several of which center around discussions of children being raised with the express purpose of later being sold to the slaughterhouse. The fictional "Mo Yan" finds himself in a conundrum over how to continue to be encouraging in the face of what he increasingly perceives to be an onslaught of literary drivel, a conundrum which is reinforced by his growing ambivalence towards his own fiction.

- About two thirds of the way through the novel, however, this boundary between the outer and inner narrative frames begins to dissolve, as "Mo Yan" ultimately succumbs to writer's block and abandons the The Republic of Wine narrative, deciding instead to travel to "Liquorland" himself to pay Li Yidou a visit. In doing so, he effectively abandons his presumptive authorial authority and steps into the same fictional space that he has already condemned to incompleteness, becoming an ironic Pirandellian character fleeing from his own authorship.

- In The Republic of Wine, the act of cannibalism constitutes an aporia of signification, on the basis of which the rest of the novel's plot is structured. The figure cannibalism similarly provides a bridge between Lu Xun's arch-canonical 1918 short story and Li Yidou's own anti-canonical literary rantings. Understood more metaphorically, the figure of cannibalism could be seen as a pivot around which regimes of cultural and literary orthodoxy revolve, whereby the orthodox canon and more "popular" or marginalized culture are seen as actually being symbiotically dependent on each other, feeding parasitically on the textual remains which the other has left behind. That is to say, just as cannibalism represents a challenge to the conventional boundaries between Self and Other, individual and collective, similarly Mo Yan's novel as a whole interrogates the boundaries between literary orthodoxy and the popular or transgressive genres against which it defines itself, together with the more ontological boundary between literary representation and the outer reality which literature seeks to denote.

- Chinese society and culture have long been haunted by the specter of cannibalism.[12] This uncanny apparition not only represents a profound challenge to the presumed sanctity of the human body (and, in the case of "survival" cannibalism, marking moments at which the very bonds of human society dissolve in the face of extreme adversity), but also, ironically, at the same time potentially standing as an ultimate gesture of social unity and filial devotion (as in the case of Chinese "endophagy," in which children are said to feed their ailing parents with flesh taken from their own bodies). Throughout the twentieth century, a variety of authors, artists, and political reformers have repeatedly used the figure of cannibalism to reflect on a range of issues relating to the constitution of social collectives and corporal subjects, while in the process effectively deconstructing the metaphoricity of the trope of cannibalism itself. While the four cases of Chinese "discursive cannibalism" which I have considered in this essay each date from different periods and involve diverse social groups and representational media, a common characteristic which they all share is that they are each located in a volatile liminal space in which a variety of social and epistemological boundaries may be problematized and rethought.

- To recapitulate briefly, the Zhu Yu controversy foregrounds the way in which the specter of cannibalism has been, and continues to be, used to reinforce perceived differences between different ethnic, national, or transnational social groups. Furthermore, even as the subsequent debates bring attention to issues of social signification, they also problematize issues of signification in general. That is to say, a recurrent theme throughout many of the debates has been one of the limits of reference: to what extent do the photographs actually denote a tangible reality? And, how does this outer "reality" signified by these texts (be it "actual" cannibalism, a performative act of cannibalism, or a performative mimicry of a cannibalistic act, etc.) ultimately impact our understanding of the implications of the subsequent debates? In the case of Lu Xun's story, one of the central issues was the boundary between "history" and "narrative": what is the relationship between narrative schemata and the historical "realities" which they seek to describe? How are we to understand the ultimate "truth value" of what appear to be metaphorical figures?

- With the May Fourth immunological metaphors, a central issue was that of how to understand the boundaries between "bodies" (either corporal or social bodies) and the heterogeneous elements (pathogens or contaminants) against which they define themselves. Finally, Mo Yan's recent novel The Republic of Wine brings us back to some key issues concerning the truth-value of ("literary") textual production, while at the same time encouraging a rethinking of the conventional boundaries between orthodox canonicity and the heterogeneous array of more "popular" or "marginal" discourses against which it seeks to define itself. Also central to the novel was another version of the semiotic quandary which we observed in the Zhu Yu debates--namely, the figure of the "perfect" simulacrum, which stymies attempts to draw meaningful distinctions between signifier and referent (which is paralleled in the Zhu Yu case by an ambiguity between signifiers with referents and those without).

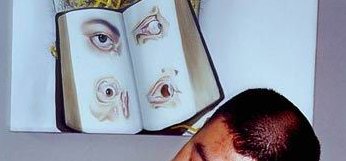

- I will conclude here by returning to the Zhu Yu performance with which I began. An intriguing detail which none of the published commentaries on the performance has (to my knowledge) hitherto remarked upon is that, in each of the endlessly reproduced images of Zhu Yu eating the human infant, he is always positioned in front of, and below, a large poster containing a representation of what appears to be an anatomy textbook (see Figure 2). The book is open to a page containing four dissected views of a human eye. Easily overlooked by viewers drawn, in horrified fascination, to the cannibalistic drama unfolding below it, these ocular images actually provide crucial insight into some of the issues involved in the production, circulation, and visual consumption of the cannibalistic images themselves.

- These images of the human eye provide an alternate focal point for this photograph, graphically illustrating the degree to which the primal scene it depicts gains significance precisely through its process of being exchanged and viewed by others. Furthermore, these defamiliarizing views of the human eye constitute a useful reminder that our understanding of the human body, even our own body, is never "pure" and direct, but rather is necessarily mediated through different pre-existing orders of knowledge, vision, and experience.

- The implications of this autonomous, disembodied gaze for our understanding of the scene as a whole are multiple. First of all, the human visual system is dissected and subjected to the cold, disinterested gaze of medical science. The resulting medical gaze, in turn, provides an ironic counterpoint to the sensationalistic, morbid gaze which the photographs inevitably elicit. As a result, these scandalous and endlessly reproduced images are not as transparently intelligible as one might think and are actually located at the site of multiply fractured gazes: spectacular, medical, anthropological, political, and epistemological. My intention in this essay has been to provide additional perspectives to each of these components of the gaze, and in the process to suggest that the figure of cannibalism may itself be seen as pointing to a crucial border region wherein conventional categorical distinctions between Self and Other, us and them, reality and representation are deconstructed and put on display.

- More generally speaking, last year's cannibalism "scandal" presents us with a problem of perception and perspective. On the one hand, a recurrent theme in most of the ensuing discussions of Zhu Yu's performance emphasized a sense of cultural distance, of voyeuristically looking into a cultural space (Asian, Chinese, Taiwanese, etc.) which is perceived as being either subtly or radically distant from the socio-political location of the perceiver. On the other hand, many of the discussions implicitly held this cannibalism up to "their own" culturally specific standards, and indeed used the transgressive implications of Zhu Yu's performance rhetorically to reinforce their own assumptions about the universality of certain cultural prohibitions.[13]

- Under the reading I have outlined above, the figure of cannibalism itself involves a paradoxical combination of identification and alterity, of violence and desire. The act of incorporating into oneself flesh of an Other with whom one shares a categorical identification, implicitly breaks down relations of alterity, even as it retrospectively reinforces them. Accordingly, this transcultural perception of cannibalism can itself provide a useful metaphor for the act of transcultural perception itself. In perceiving "other" cultures, we seek to understand, to internalize part of their inherent distance, even if only to reaffirm their inherent distance from "our" own.

- This "scandal" of cannibalism, therefore, encapsulates a compelling problem from the perspective of cross-cultural perception. On the one hand, many viewers are inclined to view cannibalism in absolute, universal terms which transcend specific cultural difference. It is simply unthinkable, according to this common view, that any human society would knowingly and willing practice cannibalism. On the other hand, to the extent that anthropologists recognize the possibility that some societies might practice (or might have previously practiced) cannibalism, they often proceed to attempt to contextualize these acts of cannibalism by reducing them entirely to the cultural level--suggesting that even actual acts of "actual" cannibalism are themselves metaphors for an underlying symbolic meaning. The question of cannibalism thus emblematizes, in a particularly graphic way, a problem which plagues all cross-cultural hermeneutics--namely, how to negotiate the competing impulses to view cultural alterity by one's own standards, on the one hand, or to bracket it as radically "Other," on the other.

- At the same time, I would suggest that the trope of cannibalism also presents a potential model for how to rethink the possibility of cross-cultural perception itself. Speaking in abstract terms, cross-cultural perception frequently contains a dimension of epistemic violence, functioning as an act of symbolic incorporation which, at the same time, retrospectively constructs and reaffirms the imaginary boundaries between Self and Other which make such reading meaningful in the first place. Like the figurative act of cannibalism itself, cross-cultural perception is typically grounded on a uneasy combination of epistemic violence and hermeneutic fusion, though the relative weightings of each of these components will naturally differ according to the specific circumstances involved. Just as the errant May Fourth white blood cells literally (re)shaped their own corporal environment through incorporative acts of "reading" alterity, I would propose a model of cross-cultural perception which is similarly grounded on acts of scopically and/or intellectually "ingesting" socio-cultural "alterity," so as to reinforce, or restructure, the perceiver's understanding of epistemic networks by which that notion of "alterity" is produced in the first place.

One question that always stymies us--that is, why cannot people eat people?

Zhu Yu

Zhu Yu

The human corporal body is, perhaps, a mere signifier. After this signifier has been developed [xianying] and fixed [dingying] on a roll of Kodak film, it becomes dark shadows [heiying]. On a sheet of wove paper that has been exposed to sunlight, it becomes a cluster of lights and shadows, with washes of ink and color added to lines and curves.

Wuming Shi, "Reflections on the Body"

|

| Figure 1 |

Afterimages of the Flesh

The eyes of the fish were white and hard, and its mouth was open just like those people who want to eat human beings.

Lu Xun, "Diary of a Madman"

When you eat a fish, you must start with the eyes.

Xu Shunying, Gushing Out

|

| Figure 2 |

Department of African and Asian Languages and Literatures

University of Florida

crojas@ufl.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2002 Carlos Rojas. READERS MAY USE

PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S.

COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED

INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

I would like to thank Eric Hayot and an anonymous reader for their suggestions. Research for this essay was supported by a University of Florida Humanities Enhancement Grant.

1. In Lacanian terms, cannibalism can be seen as a figurative "stain" or "quilting point," a point which is radically outside a certain symbolic system while at the same time providing the necessary which gives that system form in the first place. Similarly, Slavoj Zizek, in a related context, speaks of the "asystematic" points of radical alterity which are a necessary component of any system.

2. Here and throughout this essay these sorts of generalizations about "our" and "other" cultures are being used strategically, or are "under erasure" (to borrow Derrida's useful term); and, indeed, one of my arguments is precisely concerned with the re-evaluation of these accepted notions themselves.

3. In 1979 the anthropologist William Arens published a highly polemical book in which he argues that there is no conclusive material evidence that cannibalism has ever existed as a systematic social practice anywhere in the world at any point in history, arguing instead that all apparent instances of cannibalism are merely the result of optimistic over-readings of either textual rhetoric or fundamentally ambiguous material evidence (see The Man-eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy). Arens' book provided a lightning rod of contention and was useful to the extent that it brought critical attention to the latent ethnocentrism implicit in Western anthropology's longstanding fascination with cannibalism. At the same time, however, Arens' position, with its emphatic and almost messianic opposition to the very possibility of human cannibalism, can actually be seen as itself stemming from a parallel ethnocentrism, insofar as he is unwilling to confront the implications such cannibalism would have for our perception of the cannibals as anthropological subjects (see Gardner 27-50).

4. In this respect, the 2000/2001 round of cannibalism allegations can be seen as a ironic reprise of a similar series of allegations only five years earlier, on the occasion of the 1995 International Conference on Women's Rights in Beijing. At that time, foreign tabloids, Christian organizations, and even U.S. Representative Frank Wolf of Virginia were taken in by spurious claims that human fetuses were considered a rare delicacy by many Chinese gourmands. The politicians, in particular, used the story rhetorically to support their opposition to granting China Most-Favored-Nation status, but saw little need to pursue the actual allegations any further (see Dixon; this article was apparently first published in early October of 2000, shortly before Zhu Yu's performance, but may have been revised as recently as 5 June 2001 [judging by the dates of the file and its folder in the web site's publicly readable directory]).

5. On "Nietzsche fever" in China in the mid-1980s, see Wang and Cheng.

6. According to the Taiwan GIO report, Zhu Yu admitted in a telephone interview that the performance was part of the April 12 "Obsession with Injury" performances (that is, the second installment of the "Obsession" series), which does not correlate with the November 13 date cited in most other sources. It is unclear at this point, therefore, whether the repeated identification, in many Chinese reports, of the performance with the "Obsession" exhibit is in reference to a subsequent installment of the "Obsession" series, or merely an unwitting perpetuation of an original error. The question is left somewhat ambiguous in the Fuck Off catalogue, where the images are only identified by the title "Eating People" and the date, 13 November 2000 (though other images, in the same catalog, from Zhu Yu's April 13 "Obsession with Injury" performances in Beijing are clearly identified as such).

7. Lin Yü-sheng notes that there is some evidence that this piece was written not by Lu Xun himself, but rather by his brother Zhou Zuoren (who was also an accomplished and well-recognized literary figure in his own right; the "evidence" which Lin cites is that Zhou himself claimed authorship in a subsequent letter to Cao Juren). However, as Lin also notes, Zhou did not actually deny that the views he had expressed were shared by Lu Xun, but only that there were minor stylistic differences in the essay which distinguished it from Lu Xun's own work, differences which so far had gone unnoticed by the general readership. Furthermore, the essay continues to be included in Lu Xun's collected works under his own name (Lin 116).

8. For instance, the classical medical text Simple Questions of the Yellow Emperor (probably dating from the first century B.C.E.) states that "the heart functions as the prince and governs through the soul; the lungs are liaison officers who promulgate rules and regulations; the liver is a general and devises strategies." Similarly, the Tang dynasty Taoist master Sima Chengzhen (eighth century C.E.) elaborates, "The country is like the body: follow the nature of things, don't let your mind harbor any partiality, and the whole world will be governed" (qtd. in Schipper 102).

9. Chen is drawing here primarily on Metchnikoff's monograph. The subject of this essay, and of Metchnikoff's original book, is particularly poignant in that the essay was written in the year of Metchnikoff's death.

Metchnikoff's claims to fame include his discovery of the phagocytotic role of white blood cells in the immune system as well his being the younger brother of Ivan Ilyitch, immortalized by Tolstoy in his story "The Death of Ivan Ilyitch."

10. Lin Yü-sheng contrasts these three figures as follows:

Chen Duxiu, who eventually became a Marxist and the first leader of the Chinese Communist Party, was known as a man of intense moral passion, combative in temperament and fearlessly individualistic. His mind was more forceful than subtle; he was not greatly concerned with the nuances of meaning or the complexities involved in social and cultural issues. Hu Shi, on the other hand, was a Deweyan liberal and eventually became an ambivalent supporter of the Guomindang. He was a well-rounded and self-content personality, affable and urbane, and not without a touch of vanity. He possessed an alert mind, and was superficially lucid in his manner of expression, but he did not involve himself in social and cultural issues at their most difficult levels and never probed deeply into the problems with which he was concerned. Lu Xun, by contrast, was an extremely complex person, with a sharp wit and a sensitive, subtle, and creative mind. He was known for his sardonic humor and mordant sarcasm. Outwardly, he was distant and cold; inwardly, deeply pessimistic and melancholy--but with a genuine warmth and moral passion which enabled him to express the agony of China's cultural crisis with great eloquence. Politically, he was highly sympathetic to the Communists in his later years, but he eschewed formal party ties and firm ideological commitments. (9)

11. For a more detailed discussion of the relationship between these two texts, see Yang.

12. For an interesting, though thoroughly uncritical, survey of discourses of cannibalism from throughout Chinese history, see Chong.

13. On one web site discussion, for instance, the author confidently asserts that "the taboos against eating one's own are universal, and rumors about violations of these taboos are used to vilify members of competing cultures" ("Fetus")(emphasis added).

Works Cited

Arens, William. The Man-eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1979.

"Baby-Eating Photos Are Part of Chinese Artist's Performance." Taipei Times. 23 Mar. 2001 < http://www.taipeitimes.com/news/2001/03/23/story/0000078704>.

Chen Duxiu. "Call to Youth" [jinggao qingnian]. New Youth [Qingnian zazhi]. 1.1 (Sept. 1915): 1-6.

---. "The Thought of Two Modern Scientists" [Dangdai er da kexuejia zhi sixiang]. Duxiu wenji. Anhui: Anhui renmin chubanshe, 1986. 46-69.

Cheng Fang. Ni Cai zai Zhongguo [Nietzsche in China]. Nanjing: Nanjing chubanshe, 1993.

Ching, Siu-tung. A Chinese Ghost Story [Qian nu youhun]. Hong Kong: Star TV Filmed Entertainment, 1987.

Chong, Key Ray. Cannibalism in China. Wakefield, NH: Longwood Academic, 1990.

Dixon, Poppy. "Eating Fetuses: The Lurid Christian Fantasy Of Godless Chinese Eating 'Unborn Children.'" Adult Christianity. 2 Oct. 2000 < http://www.jesus21.com/poppydixon/sex/chinese_eating_fetuses.html>.

"Fetus Feast." Urban Legends Reference Page. Ed. Barbara Mikkelson. 19 Jun. 2001 <http://www.snopes2.com/horrors/cannibal/fetus.htm>.

Gardner, Don. "Anthropophagy, Myth, and the Subtle Ways of Ethnocentrism." The Anthropology of Cannibalism. Ed. Laurence Goldman. Westport, CT: Bergin, 1999. 27-50.

Girard, René. Violence and the Sacred. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1979.

Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Hu Shi. "Ibsenology" [yibusheng zhuyi]. Hu Shi zuopinji. Vol. 6 Taipei: Yuanliu chubanshe, 1986. 9-28.

Hua Tianxue, Ai Weiwei, and Feng Boyi, eds. Fuck Off [Bu hezuo de fangshi, which literally means "an uncooperative approach"]. Shanghai: Eastlink Gallery, 2000.

Lin Yü-sheng. The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Antitraditionalism in the May Fourth Era. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1979.

Lu Xun. "Diary of a Madman." Lu Hsun: Selected Stories. Trans. Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang. New York: Norton, 1977. 7-18.

---. "Random Thoughts #38." New Youth [Qingnian zazhi]. 1918.

Mao Zedong. "On New Democracy." Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung. Vol. 2. Beijing: Foreign Language, 1965. 339-384.

Metchnikoff, Elie. The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies. New York: Putnam's, 1910.

Mo Yan. The Republic of Wine New York: Arcade, 2000.

Ong, Aihwa. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham: Duke UP, 1999.

Republic of China. Government Information Office. "Rumors of Fetus Eating in Taiwan Traced to Mainland Performing Artist". 18 Jul. 2001. < http://www.taipei.org/official/rumors/rumors.htm>.

Schipper, Kristofer. The Taoist Body. Berkeley: U of California P, 1993. 102.

Wang, Jing. High Culture Fever: Politics, Aesthetics, and Ideology in Deng's China. Berkeley: U of California P, 1996.

Wang Shuo. Please Don't Call Me Human. Trans. Howard Goldblatt. New York: Hyperion, 2000.

Wang, Val. "Sadistic Art? A Roundtable with Performance Artists." ChineseArt.com 3:2 (2000) < http://www.chinese-art.com/artists/openstudio.htm>.

Wu Hung. Exhibiting Experimental Art in China. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2001.

---. Transcience: Chinese Experimental Art at the End of the Twentieth Century. Chicago: U of Chicago Museum of Art, 1999.

Wuming Shi. "Reflections on the Body" [Dongti ningsi]. Expressing Emotion of Mist and Clouds [Shuqing yanyu]. Taipei: Wenshizhi chubanshe, 1998.

Xu Shunying. Gushing Out [Daliang liuchu]. Taipei: Hongse wenhua chubanshe, 2000.

Yang, Xiaobin. "The Republic of Wine: An Extravaganza of Decline." positions 6.1 (1998): 6-32.

Yu Hua. "Classical Love." The Past and the Punishments. Trans. Andrew Jones. Honolulu: U of Hawaii P, 1996. 12-61.

Zheng Yi. Scarlet Memorial: Tales of Cannibalism in Modern China. Trans. and ed. T.P. Sym. Westview: Boulder, CO., 1996.

Zizek, Slavoj. The Sublime Figure of Ideology. London: Verso, 1997.