"Be deceived if ya wanna be foolish": (Re)constructing Body, Genre, and Gender in Feminist Rap

Suzanne BostJames Madison University

bostsm@jmu.edu

© 2001 Suzanne Bost.

All rights reserved.

- Hip hop music gets a bad rap. Far too often it seems to be about the objectification of women, but hip hop artists position themselves around this topic in very complex ways. This complexity is missed when critics ignore the relationship between the verbal, musical, and corporeal levels of hip hop performance. Even as they make a show of their bodies--giving the audience "something to look at" as Salt 'N Pepa do--female rappers often disrupt misogynist objectification by creating dissonance between the multiple layers of their performance. This dissonance reflects both a postmodern practice of resistance--subversion from within dominant modes of racialized and sexualized containment--and a long-standing tradition in African American cultures, from slave songs and quilts with hidden meanings to linguistic games and signifying stories. Within both traditions, artistic statements circulate about more than they seem to be.[1] It is impossible to say just what they are "about," as word, body, rhythm, and melody often communicate divergent messages.

- In this paper, I analyze musical texts that refuse containment and categorization as much as the bodies they represent, fusing rap, jazz, and funk with poetry, performance art, and fashion. A number of strong female voices have emerged from within the hip hop industry, using rap music forms to assert their own identities and to critique the limited identifications offered for women within the genre.[2] Their strategy is consistent with hip hop arts like dissing, posturing, mastering, mixing, and parodying antecedents with multi-tracked samples.[3] They employ these artistic methods in powerful raps that seem, on the lyrical level, to echo slavery's reduction of Black women to body and capital; but rhythm, tone, melody, and voice actively subvert this objectification. Poets Toi Derricotte and Jessica Care Moore suggest, in my epigraphs, that the English language requires physical contortions--twisting faces and dancing out of slave skirts--if it is to reflect African American identities since English has been antagonistic to Africanist values, experiences, and corporealities since slavery.[4] Yet using the dominant language is the only sure way to address the dominant audience. In order to gain visibility within a racist and misogynist culture, the artists I analyze invoke the objectification of Black women but twist their content to exceed this framework.

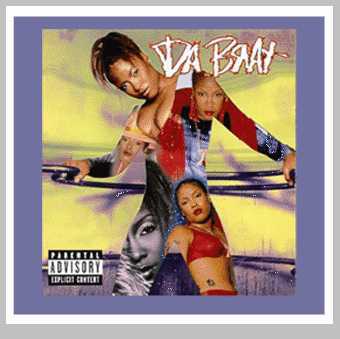

- I am most interested here in the recent work of Da Brat--the first solo female rapper to go platinum, and recently named the best woman in hip hop by Russell Simmon's "One World Music Beat." Other female rap acts--Queen Latifah, MC Lyte, Yo-Yo--more clearly critique misogyny, but the ways in which they enact this critique distance them from the dominant media images of hip hop gender roles and thus limit their audiences. To a certain extent, Da Brat's tremendous visibility can be attributed to the ways in which she invokes the media obsession with rap's misogyny, "booty call," etc. Using the familiar criteria gains Da Brat a much wider audience than her more clearly "feminist" contemporaries, and the size of this audience makes her a serious political force.[5] While the nature of that political message might be ambiguous to her audience--part of the risk factor involved in the double-voiced, often parodic nature of rap--her aggressive assertion of her own mastery of the form, her direct attack on audiences' consumption of her image, and her excessive layering of hip hop gender roles clearly do bend audience expectations about gender.[6]

- My argument is based on frameworks that may seem incommensurate--hip hop, postmodernism, and feminism--so I want to be clear from the start how and why I invoke these terms. Hip hop is, by nature, contestorial, resistant, and political. Rob Winn's definition, from The Voices of Urban Renewal, is useful: "Hip hop took street poetry," formed against the "backdrop" of 1960s political contestations, "and made it accessible to the masses," removing poetry "from the sterile confines of the classroom" and giving it "a salient street value."[7] Much recent rap music has been distanced from these political origins, but it retains the power to communicate messages on the streets. Although late capitalist industry has commodified its raps and saturated the media with a one-dimensional image of drug-addicted, violent, misogynist black masculinity, hip hop remains self-reflexive about this gangsta image as well as its own commodification, refusing to reflect any one message. Postmodernism offers strategies for interpreting the self-reflexive irony in hip hop expression. The protest that hip hop stages against black otherness is one that performs these images for the simultaneously fearful and desirous white consumer, and often signifies against them, as in Henry Louis Gates's model of "repetition with a difference."[8] Similarly, David Foster Wallace's analysis of the content of rap music argues that "the serious rap places the very theme of 'theme' under erasure... by being... self-conscious and radical enough overtly to address the very contexts of history and marginalization that have already 'read' the black and white communities in the racial/political/sexual/economic prejudices we respectively bring to rap's hearing" (Costello and Wallace 98). The politics of hip hop often emerge as hidden or double meanings, the recognition of which requires both attention to internal contradictions and an understanding of African American traditions of artistic expression. Without an insight into the destabilizing nuances and referential layers of these raps, listeners might hear nothing but a simple repetition of myths of black otherness.[9] Russell Potter, too, cautions that "hip-hop's way into the spectacle is also its greatest danger: by picking up these narratives and Signifyin(g) against them, it runs the constant risk of being collapsed and conflated within them by those who don't 'get' the doubleness of Signifyin(g)" (134). Yet these risks, the openness to multiple, conflicting (mis)interpretations, help hip hop to resist appropriation by, and circumscription within, dominant paradigms. It also means that hip hop never offers a closed, dictatorial message, but rather a web of possibilities, allusions, ironies, and contradictions within which listeners participate in the production of communal meanings.

- Many female hip hop artists (Queen Latifah, for example) reject the term "feminist" because of its historical alliance with Euro-American middle-class concerns, its frequently inaccessible theories, its tendency to center exclusively on sex/gender as markings, and other contradictions of hip hop principles and Black urban experience.[10] I pair "hip hop" with feminism in order to de-privilege Euro-centric and elitist strands of feminism and to decenter hip hop's famed misogyny. Many rap lyrics are indeed misogynist (gangsta rap, most particularly), but this misogyny has become a myopic media obsession employed, I would argue, in order to dismiss the political value of hip hop.[11] This obsession also obscures the visibility of overtly feminist rap artists since they do not fit the dominant image. In order to revise the gender image most often associated with hip hop culture, it is important both for feminists and for hip hop fans to be able to see rap music in a feminist light. Rather than merely rehashing the critique of some rappers' violent misogyny, I find it more valuable to analyze rappers who challenge media assumptions about hip hop gender politics.

- I do not draw on hip hop as a mere example for an academic feminist analytic; rather I have come to hip hop in my search for a critique of misogynist corporeal inscriptions that communicates beyond the theoretical frameworks of postmodern feminism. In music, aural cues, instruments, and performers' bodies ground lyrics in specific cultural contexts. Music can signify beyond the language that Derricotte and Care Moore suggest is so ambivalent for African Americans. It "puts the body itself to use," using tone, nuance, movement, and tension to communicate beyond dictionary definition (Derricote 162). Feminist rap, in particular, is compelling for the ways in which it speaks to the concerns of African Americans, of young people, and of those who lack economic or academic privilege. The feminism I find in Da Brat and others addresses these concerns and critiques the specifically racialized misogynist morphologies assigned to African American women since slavery.

- Any politically effective, culturally aware feminist

theory should engage the theories that are developing in popular culture.

Not to do so would imply, falsely, that views from academia and from the

streets have nothing relevant to offer each other. I take seriously the

insistence of Russell Potter, and others, that:

In the essay that follows, I enact a dialogue between academic knowledge and hip hop knowledge. I draw on the well-established insights of feminist and anti-racist theorists of the body and performance--such as Judith Butler, bell hooks, Hazel Carby--and I bring these into conversation with the kinds of insights that may be found within the framework of hip hop culture itself.[12]Academic knowledge and hip-hop knowledge need at least to be on speaking terms, and such a dialogue depends on academics seeing that rappers have their own protocols, their own epistemologies, which cannot simply be read according to an academic laundry list of theoretical questions. (Potter 152)

- I draw especially on the work of feminist spoken-word artists such as Ursula Rucker, Dana Bryant, and Sarah Jones--performers who overtly critique misogyny within the terms of its circulation in hip hop culture. For instance, Sarah Jones's description of her own strategies of resistance can help to uncover that which is empowering, but often unrecognized, in Da Brat's tremendously publicized message. In a personal interview, Jones explains: "It's a firm structure.... [Images of women in hip hop as "bitches and hos"] are not going away from the outside.... You have to play both sides... get in and finagle around... play within it while you do your best to poke holes in it." The "structure" that many young African American women are subjected to is specifically rooted in hip hop stereotypes and the media's vilification of "the ghetto." Rap music offers the most visible response to this structure from within "the ghetto." Since so much of the meaning of rap music is produced in communal interpretation, that meaning emerges from dialogue with stereotypes familiar to the community, other raps, and communal events. To assess the communal value of the meanings that Da Brat puts into play, then, I engage feminist methodologies that emerge from within a hip hop milieu. Rucker provides a model for rescripting the reduction of women in hip hop to sexual objects. Bryant provides a model for highlighting the excess, the real body that the "bitches and hos" stereotype cannot contain. And Jones outlines a critique within and against hip hop commodification. All three begin by emphasizing the artificiality of objectified images of Black women and undermine these images with excessive imitation, ultimately clearing space for re-imagining hip hop gender.

- Despite media-bred assumptions, women rappers are not an anomaly.

Though less visible to mainstream audiences, their contributions have

been integral to the formation of hip hop culture. As Laura Jamison

writes in her essay "Ladies First":

According to studies by Jamison, Tricia Rose, Cheryl L. Keyes, Murray Forman, Nancy Guevara, William Eric Perkins, Helen Kolawole, and Joan Morgan, women helped to shape the tradition of rap music--and, according to Guevara, break-dancing, tagging, and other hip hop art forms--since the 1970s. As DJs, MCs, graffiti artists, and break-dancers, women have "mastered" the arts of digital technology, declared their authority, and defied constraints on the body and physical endurance. Their visibility is currently obscured, however, by media that love to hate rap music and, therefore, only see "gangsta rap" and "booty call."Macho antics like posturing, bragging, and throwing attitude are the heart and soul of the rhyming tradition, which is probably why rap is usually considered an inherently male form (rump shakin' videos and bee-yatch-laden lyrics probably don't help dispel the idea, either). Female MCs have traditionally been viewed as interlopers--either butchy anomalies or cute novelties who by some fluke infiltrated a boy's game. But the fact is, while fewer in number than men, women have been integral to rap since its formative years (a claim that can't be made for the other dominant postwar pop music form, rock 'n' roll). (177)

- Images of women in hip hop today are filtered through mainstream masculinist lenses in which female rappers are reduced to gender transgressors--wearing "male-derived attire" and punctuating their lyrics with frequent "motherfucker's"--or sexual objects--"spectacle rather than [part of] the production process," "tramps and whores," "nasty," "hypersexed... hoochie mamas" (Keyes 208-209; Forman 47; Guevara 56; Morgan, "Bad Girls" 76). On the one hand, the politically active, self-assertive Queen Latifah is routinely labeled a lesbian--an intended critique meant to signify "unfeminine"--for her refusal to conform to the image of sex object.[13] This reaction reflects a heterosexist gender binary that conflates strength with masculinity and with desiring women. On the other hand, acts like Salt 'N Pepa and Da Brat are often perceived only as sexual commodities. As Kolawole says of Salt 'N Pepa, "Their liberation has not extended to being able to appear on stage without showing considerable amounts of cleavage or being clad in tight-fitting lycra. The image is strong, but it is still designed to be acceptable to men" (12).[14] This language defines female rappers only in reference to heterosexual masculinity, either as appropriated goods or as amorous spectator.[15] In Spectacular Vernaculars (1995), Potter suggests that the "politics of sexuality in hip-hop" revolve around heterosexuality: "while assertive, aggressive sexuality is a key ingredient of hip-hop attitude, it has so far almost always been heterosexuality" (92). Following the gender split in this hetero-framework, Potter divides women rappers into two "schools," "which could be called the 'sex' school and the 'gangsta' school" (93).[16] In hip hop vernacular, "gangsta" and "ho" seem to function as the "criteria of intelligibility" for women, the frames through which they are seen.

- Da Brat, Ursula Rucker, Dana Bryant, and Sarah Jones

specifically invoke this binary in order to critique it. Rebecca

Schneider's terms for assessing feminist performance art, in The

Explicit Body in Performance, illuminate the ways in which these

artists' explications of African American women's bodies critique the

normative lenses through which they are viewed:

When this theoretical approach is applied to women hip hop artists, their focus on sex and the body emerges as something more critical than simply assuming women's sexual nature or catering to heterosexual masculinity (though they might seem to conform to these expectations on a superficial level). Rather than simply imitating their male counterparts, these artists interrogate the hidden meanings attached to their bodies as they have been defined historically, denaturalizing the body as we know it--"haunted" by racist and sexist discourses.[17]Unfolding the body, as if pulling back velvet curtains to expose a stage, the performance artists in this book [including Carolee Schneemann, Annie Sprinkle, Karen Finley, and Spiderwoman] peel back layers of signification that surround their bodies like ghosts at a grave. Peeling at signification, bringing ghosts to visibility, they are interested to expose not an originary, true, or redemptive body, but the sedimented layers of signification themselves. (2)

- Da Brat, Rucker, Bryant, and Jones dissect the body as a sedimentation of heterosexist, racist, and capitalist imperatives. For them, the "ghost" story is the legacy of slavery and its narratives of legitimization that defined Black women as sexual property or "oversexed" animals. As Bryant says, "There's nothing wrong with being a wild woman, but we've been bludgeoned by that image.... It's important that [the image] be harnessed by women and redefined for what it truly is" (qtd. in McDonnell 78). This critique resembles a postmodern (or Butlerian) dynamic of resistance: attacking the image from inside by revealing its inner workings. Rather than simply objectifying themselves in exchange for power, these artists effect a powerful critique of the misogynist status quo by repeating "gangsta" and "ho" imagery excessively so as to expose the grotesque underlying assumptions.

- Ursula Rucker is overt in her feminist message, and, perhaps as a direct result, marginal in the hip hop industry, with single-track recordings on albums by other artists. According to the on-line African American Literature Book Club, "Counteracting male artists who casually linger on tales of black whoredom, Ursula plays an essential role in the rise of a new crop of female recording artists who deliver strong, intelligent, and visionary feminine flavor" (<http://authors.aalbc.com/ursula.htm>). I would argue that both Da Brat and Rucker critique these "tales of black whoredom," but their approaches reflect different choices in self-promotion. While Da Brat, to retain her position at the forefront of the industry, must present an image that appears superficially consistent with hip hop stereotypes, Rucker more aggressively rejects "gangsta"/"ho" mythology in forthright spoken-word pieces, such as "E.R.A." and "Return to Innocence Lost."[18] Da Brat's success in the recording industry, her participation in MTV culture, and her use of familiar hip hop iconography--"ho"-styled attire, braids, and Glocks--gain her a larger audience, and yet her ultra-fast-paced raps and her participation in "gangsta"/"ho" imagery make any feminist content difficult to decipher. Rucker's message is less ambiguous, she speaks more slowly, and her lyrics are clearer. Her clarity prepares listeners for the type of subversion that is less obvious in Da Brat. And by recording individual pieces on three albums by the popular hip hop band The Roots, she has a "captive audience" of rap fans who recognize her direct critique of "gangsta"/"ho" mythology.[19]

- In "The Unlocking," the concluding piece on The Roots's album Do You Want More? (1994), Rucker works within and against the "ho" image to reveal its status as myth. Her strategy in "The Unlocking" is much like hattie gossett's in "is it true what they say about colored pussy?" She engages a derogatory term that hurts women today in order to attack it directly. Rucker's powerful and troubling piece narrates a scene in which a woman (presumably a prostitute) receives eight different men in serial fashion.[20] She is sodomized, asked to perform oral sex, and called "bitch" and "whore." Yet the whore ultimately asserts, "this was a setup," posing the scenario as a display constructed for a witness, or a trap set for an unsuspecting victim, rather than an unmediated reality.[21] It is a "masquerade," in the sense described by Mary Ann Doane's psychoanalytic film theory: with "potential to manufacture a distance from the image, to generate a problematic within which the image is manipulable, producible, and readable by the woman" (Doane 191). Rucker makes overt the staging of a whore to render the image "manipulable." She "defamaliarize[s] and destabilize[s]" the "ho" image by highlighting the distance between the woman and the postures that she is expected to assume (186). The whore is revealed to be a "sedimentation" (to borrow Schneider's term) of racist and misogynist interests rather than a natural embodiment. Rucker shows how women are often seen as reflections of misogynist myths, and she renders this reflection so literally as to expose the dehumanization behind it. She also exposes the inaccuracy of the eight men's objectifying perceptions of the whore and the hollowness of their staged masculinity. Witnesses to the setup receive a warning regarding the violent assumptions behind "gangsta"/"ho" imagery.

- The whore is first perceived through the narrative's outer frame, which records one man calling another on the phone and talking about a "fly" woman who is a "swinger." These men's voices are then silenced and Rucker's voice assumes narrative authority with the words, "I, the voyeur, appear," framing the whore and the men's consumption of her within the gaze of a female narrator, and making listeners aware of their participation in this voyeuristic gaze. The whore--herself silent until the end of the piece--is triply framed, by the listener "watching" the female narrator, who in turn watches the men as they address the whore. This self-reflexive framing highlights the ways in which all women are "framed" by sexually objectifying assumptions. The scene is described as a "ritual," her mouth is described as "framed," and man #2 tells her to bend over "like a real pro whore." The "like" in this last example establishes "whore" as a role the woman performs--with expected rituals, poses, and positions--rather than something that she is. Rucker literalizes and critiques the dehumanization of prostitution as the background sound is mixed with barely audible noises that sound like animal calls, while the whore is "digging" her "soft and lotioned knees" into the floor. Such excess takes any pleasure out of the spectacle by rendering it hyper-real, disturbing audiences by forcing them to witness these shocking images in vivid detail.

- Though the scene originates in the perception of women

as whores, Rucker's use of sound allows her to disrupt this

perception.[22] Phones ringing

"mid-thrust" and meaningful bass line pauses interrupting copulation run

counter to the dominant narrative (as in the line "he never could quite

see above... her mound," which separates "her mound" from the seeing).

Reminders that the woman has an identity beyond sex object also intrude

upon the extended sex scene:

Rucker undermines the whore's "ho" image by speaking of her sexual agency, her "sanctified places," and her own "in-house spirits." With increasing frequency as the narrative progresses, the narrator insults the men's sexual prowess in the hip hop tradition of "dissing": she attacks the men where it hurts most, revealing the "abrupt" endings to their sexual endeavors, critiquing man #5's "pseudo-thickness," describing man #6's prowess as "inactive shit," and concluding, after his "pre-pre-pre-ejaculation," that "she just wasted good pussy and time."So one goes north, the other south.

To sanctified places where in-house spirits will later

wash away all traces of their ill-spoken words and complacent faces.

And then, like their minutemen predecessors,

lewd, aggrandized sexual endeavors end abrupt

'cuz neither one of them could keep their weak shit up.

Corrupt, fifth one steps to her,

hip hop court jester, think he want to impress her.

"Hey slim, I heard you was a spinner,

sit on up top this thick black dick and work it like a winner."

With a quickness he got his pseudo thickness all up in her

but suddenly he... stops mid-thrust.

[phone ring]...

Got him stuck in a death cunt clutch.

He fast falls from the force of her tight pussy punch,

just like the rest of that sorry-ass bunch. - Ultimately, the whore's body resists its construction as object when her "pussy" "punch[es]" man #5, taking on active, aggressive, penetrative form. Following these assertions of subjectivity, the whore appropriates "gangsta" style violence from men on the streets by taking up a "fully-loaded Glock" and aiming it at the "eight shriveled-up cocks" in her bedroom. As with Da Brat, Rucker's whore threatens "ho" mythology by embodying the "gangsta" at the same time, coupling what are supposed to be opposite poles. How can the "ho" be regarded as a passive object of men's sexual consumption when she has a gun trained on their penises? The whore ultimately de-authorizes phallocentrism by objectifying the men's penises and speaking with her own lips, when she "parts lips, not expressly made for milking dicks." This description invokes and overturns the misogynist portrayal of women's mouths--earlier described by man #4 as "DSL's" [dick-sucking lips]--as holes to be penetrated by penises. With another significant pause, "and then... she speaks," the whore authorizes herself as subject and postures as such: "Now tell me what... what's my name." This demand for recognition is common in male rappers' contests for mastery, and the whore asserts it "now," after she has moved beyond her objectified role. The final sound is the "cock" of a gun, an unambiguous threat that silences the "cocks" of the men and leaves power in the hands of the woman. By reversing the power dynamic in the "ho" narrative, Rucker deconstructs the gendered myths that underlie it. From this conclusion, which seems all the more powerful in juxtaposition with the whore's initial objectification, women can demand to be recognized as individual subjects.

- It is difficult to characterize Dana Bryant's music in terms of available categories; rap, R & B, gospel, spoken word, and World Beat would all be applicable. She is also a Nuyorican Poets Café Grand Slam Champion (<http://www3.mistral.co.uk/wallis/dana.htm>). As Evelyn McDonnell writes, in a Ms. magazine article entitled "Divas Declare a Spoken-Word Revolution," Bryant resists containment within any single genre and "maintain[s] [her] freedom and complexity from inside the record biz" (78). In her album Wishing from the Top (1996), Bryant moves chameleon-like between musical styles, and simultaneously pays tribute to and signifies upon her diverse foremothers: grandmothers, worshippers at a Southern Baptist church, makers of African-derived cuisine, wearers of "Dominican girdles," Barry White fans, Ntozake Shange, bell hooks. In "Canis Rufus: Ode to Chaka Khan," Bryant initially masquerades as funk star/sex goddess Chaka Khan by assuming a funk musical script and exploring Chaka's stage construction. This song, like Rucker's, interrogates the assumptions behind "ho" imagery. Bryant pulls back the curtains and uncovers the layers of Chaka's performance--as the artists in Schneider's study "peel back layers of signification"--to deconstruct the inscription of her body.

- The audience "sees" Chaka one piece at a time, first

"knifin' the curtain / open with bejeweled fingers," then "her head / laden

with citrus sweetened hairs-- / medusian ropes swingin'," moving down to

her "lips / plentiful soft / and smackin' / sweet badass's," then:

This gradual revelation of body parts resembles a striptease, but each part is covered in jewels, scents, dyes, and feathers. This body is an artificial composite. It is excessively styled, exotic, and fragmented, never whole, natural, or naked, despite the description of Chaka's stomach as "stripped." As a striptease, these lines show how a woman's "naked" body is never truly naked, but always inscribed (or "laced") with assumptions attached throughout history. It is a sedimentation of constructions, assigned a list of mythic types: "circe," "demoness," "the voodoo chile / jimi hendrix plucked strings to conjure up." All of these inscriptions incorporate "ghost stories" left from slavery: the perception of Black women as sexual demons or exotic artifacts and the myth that they held power to cast spells on unwitting victims. The "voodoo chile" is not just Jimi Hendrix's fantasy, but also that of slave masters who wished to deny their own culpability for sexual relations with slaves.[24]Her stomach stripped of all but bronze blue flesh

beaded rings of baby peacock feathers- her hips swayin' chains

of lilies laced wid sense-amelia[23] - About two-thirds of the way through the song, the gaze

travels down Chaka's body to her "crotch / explodin' light- / mound of

venus rainin' salt n flame on open lifted stadium faces." These lines

reveal the body in front of an audience and blow it up in their faces.

They also introduce a transition in melody and instrumental background. A

hard-rapping, heavy-rhythmed, deep-bassed sound overtakes Chaka's funky

one at this point. Although it would be inaccurate to say that one

musical sound is Bryant's more than any other, this change in style makes

it seem as though Bryant is asserting her own musical authority and

taking a step back from Chaka's funk role. The effect is exhilarating and

creates a new perspective. Bryant says of this piece:

This statement suggests that music can liberate Black women from racist and sexist containments and the "fetters" and silences that are left from slavery. Indeed, it is sound that detonates the objectified body of Chaka Khan. The instrumental and vocal components shift at the same time as the lyrics describe Chaka's cunt exploding and raining down upon the uplifted gazes of spectators. The body as sexual spectacle is now--from this new perspective--too excessive to be contained by skin. It resists the contours of "object" and turns against its desiring viewers.My poem isn't necessarily about Chaka. It has more to do with the feeling that sound makes happen in me, the possibilities it opens, to break free of the fetters of self-censorship. It's important for me as a black woman because I've always shrunk away from my sexuality, because it's been wielded as a blunt instrument against me. (qtd. in McDonnell 78)

- After creating this critical distance from Chaka Khan,

Bryant raps:

These lines describe the "literal" body as excessive, implying that no one wants the "real" body, but merely the myths, symbols, and images inscribed upon a passive form. This body is active, reaches out at spectators. As with the punching "pussy" in Rucker's piece, the "real" crotch challenges an objectifying gaze. The rain from Chaka's "mound" makes her body grotesque and immanent, unlike the song's first image of her, viewed on stage from a distance. Like Rucker, Bryant renders the "ho" too much to be desirable. Yet Bryant's strategy is a bit different. She exposes the literal "matter" behind the masquerade, insisting on the reality of the body that has been so culturally inscribed. And the relationship between the actual body and the "ho" image is an antagonistic one. If we could take a step back to view the body without the mediations of exotic feathers and "medusian ropes"--a step that Bryant's song simulates with the change in musical perspective--"salt n flame" would detonate the illusion in our faces.[25]she too literal · she too extreme · much too

seamy · much too obscene · I say ·

SCREAM SISTA - Performance artist/MC/poet/activist Sarah Jones, like Rucker,

also speaks from the "underground" of hip hop culture

(<http://www.survivalsoundz.com/sarahjones/>). Yet by

performing in

different types of venues--including the hip hop Lyricist

Lounge, the

Nuyorican Poets Café, Lincoln Center, the United Nations, and a

variety of theaters and universities across the country--Jones gains a

large and diverse audience.[26] From

these cross-cultural locations, her work exceeds any single gender

framework--such as "gangsta"/"ho"--and she assumes multiple, fluid,

border-crossing identities. She also elides heterosexuality as obsession

by refusing to apply gender codes to many of her subjects (even in her

sexually seductive piece "Metaphor Play").[27] Her poem, "your revolution" (a "remix" of Gil

Scott-Heron's famous spoken-word piece, "The Revolution Will Not Be

Televised"), directly critiques gender roles in hip hop culture:

These last lines are an allusion to the 1988 song, "Wild Thang," (by 2 Much, featuring female rapper, LeShaun), which explicitly narrates a woman's pleasure in heterosexual intercourse. This song was later sampled in LL Cool J's 1996 "Doin It," a song that commodified the woman's sexuality by going platinum on the back of LeShaun's lyrics. Jones indicates that revolution will not be found within these frames of reference. She invokes these binary gender codes (masculine/feminine, subject/object, penis/crotch) to critique both the centering of masculinist heterosexual consumption in hip hop politics and the commercial exploitation of hip hop's legacy (represented by appropriations of Scott-Heron and LeShaun).your revolution will not happen between these thighs

the real revolution

ain't about booty size...your revolution

will not find me in the

backseat of a Jeep with LL

hard as hell

doin' it & doin' it & doin' it well (Jones 32) - In a Village Voice review, James Hannaham praises Jones, herself mixed-race, for her "mastery of the mix." Not only does her work remix elements from previous artists' songs and poems, but, according to Hannaham, "she revels in human contradiction, particularly the irony of searching for a politics of identity in a realm where identity and image whirl in an unstable pas de deux" (108). As Hannaham tells Jones's story, he employs a postmodern rhetoric that unmoors image from identity. He describes her life as a series of performances and tactical roles, citing her "code-switching" between "D.C. 'Bama slang and 'whitey-white Sarah'" and her "'hoochie mama' phase" (108). Jones's one-woman show Surface Transit captures this fluidity and grounds it in current political struggles against racism, sexism, and homophobia. In a series of monologues, she assumes roles that cross lines of age, race, and sex.[28] She highlights the constructedness of each identity by performing costume changes on stage, projecting a different bright color onto the backdrop for each monologue, and exaggerating each "type" in terms of image, phraseology, and racist stereotype. Each character is excessive and parodic: including a racist, hypochondriac Jewish grandmother; a macho, homophobic Italian cop; and a Black youth with an impenetrable hip hop vernacular. Seeing all of these identities enacted through Jones's body reflects both a postmodern challenge to essence and a specifically racialized survival strategy of molding oneself to adapt to different contexts.

- Three personae in this piece are particularly self-reflexive--highlighting aspects of Jones's own artistic identity--and illuminating for a study of feminism and hip hop. As "Sugar Jones," a West Indian actress, Jones critiques the entertainment industry for casting Black women only for "Booty Call" or "Hoochies in the Hood." "Rashid" leads a twelve-step program for recovering MCs, in which he recites one of Jones's hip hop spoken-word pieces, "Blood," punctuated by self-critique for his failure to overcome the habit of rhyme. "Keysha" is a young and somewhat naive college student from Brooklyn who recites another Jones poem, "your revolution," and who refuses to be a "video ho."[29] Jones parodies hip hop poses when a "horny-ass-wanna-be-player" tries to pick up Keysha, but she cannot hear his voice over his booming car stereo. Through Keysha, Jones confronts gender options presented to young, urban African American women, and Keysha, like Jones, wants to choose education and poetry. As Sugar, Rashid, and Keysha, Jones asserts an attempt to distance herself from "gangsta" and "ho" stereotypes; but just as Rashid unconsciously succumbs to rhyme, she is inevitably co-opted by them, too. She assumes the very roles that she critiques, and destabilizes them from within.

- In "Blood," Jones denaturalizes images of African

Americans as excessive consumers--and compares these images to the

marketing of Black bodies as commodities during slavery--to expose the

exploitative workings of commodity capitalism upon both male and female

bodies:

It is a bad fit: the Black body does not fit into the dominant culture's sneakers; the price does not correspond to the conditions of production. Past and present, slavery and advanced capitalism merge: the feet that don't fit into Nikes and Reeboks are syntactically the same feet "sank in rusted chains" (12). Like Bryant, Jones highlights the traces left from slavery that mark Black bodies today, but Jones targets capitalism itself as the source of these markings. She mimics the voice of a slave trader examining the survivors of the Middle Passage to assign them a price, followed by parodic images of African Americans' supposed desire for white-produced designer goods today.[31] The irons that marked "black butts" directly precede "those for / pressing and curling naps yanked straight" and the designer labels on the back pockets of blue jeans. In both economies, white capital is opposed to Black body as an antagonistic force attempting to mold feet, butts, and hair in unnatural ways. Jones splices the auctioneer's call for bids on "top of the line" slave bodies to Calvin Klein in order to suggest that the contemporary commodification of Black bodies is as dehumanizing as slavery was, and it is still whites who profit. Both slavery and consumer capitalism rest on the exploitation of Black value, effacing Africanist value systems beneath commodity values typically assigned by the dominant (white) culture. Jones highlights the disjuncture between white capitalist assumptions and black corporeality by inserting drum rolls between the voices of the slave trader and the Black consumer and by exaggerating imitated accents to draw attention to the difference in perspective.They [black feet] don't fit into any shoes

not Nikes

not Reeboks

they make them in sweat shops across the sea

turn around and sell them right back to you

and you

and me

for fifty times their value (Jones 12) [30] - Jones's critique of capitalist manipulation of African American identity extends to complicit hip hop artists. "Blood" shifts into the first person plural, lamenting, "we'll tuck our low self-esteem into some Euro-trash jeans / some over-priced shit from Donna Karan / then we'll toast with Hennessy / to covert white supremacy" (14). This line could be an allusion to Da Brat's hit song from Anuthatantrum, "Sittin on top of the world": "Sittin on top of the world / With 50 grand in my hand / Steady puffin on a blunt / Sippin hennessy and coke."[32] Significantly, Jones herself wore black leggings with a visible Donna Karan logo during a June, 2000 performance of Surface Transit. Jones clearly implicates herself in this commodification when she cites "backs that cracked beneath the weight of slave names / like Jones, Smith, Johnson, Williams..." (12). White logos on black bodies represents an unnatural and effectively racist appropriation, but such commodification has saturated African American culture to such an extent that one must resist from within. Logos legitimize bodies and make them visible in the terms of the dominant American culture; being a consumer engages that culture in its own language.

- Jones's resistance occurs within these terms, in the form of excess, fluidity, shifting from role to role and brand to brand in ways that defy proprietary circumscription by any one identity or corporation. Ownership, itself, either by slave trader or clothing designer, is defied as "blood" moves rapidly from one pair of pants--or one master's name--to the next in a long list of brands: Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Guess, Fila, etc. Disloyal consumers do not honor any label.

- The dominant culture's shoes and jeans--pushed on Black youth with inflated prices--operate politically in the same fashion as constricting race and gender assumptions. Although African American bodies might be culturally inscribed (with designer name brands as well as the imagery of the dominant culture) today, much like when they were literally branded as slaves, Nike cannot contain these bodies, Jones insists. As Rucker and Bryant subvert gendered containments, the "afroMadonna and child / and child / and child," invoked in "Blood," exceeds the limits of the dominant paradigm. Jones makes this point in her words as well as in her choice of genre, or, rather, in her fusion of genres, which cannot be contained by the marketing categories of poetry, theater, or music. The lines "Nawsuh, I'se don't want to wear yo' britches / Nawsuh, I'se don't want to grant yo' wishes" are spoken during an extended break in the drumbeat to centralize their message (15). Jones herself refuses to be published or recorded by any major corporations. (Her chapbook of poems, your revolution, is self-published and critiques the publishing industry with a mock publication line attributed to "iquitthiswretchedjob press.") Her work defies any sort of reproduction, which would inevitably fail to capture some aspect of the performance (oral, visual, rhythmic, physical). Like the feet that overflow Nike shoes, Jones is an unruly commodity in the entertainment industry.

- Da Brat fuses "gangsta" and "ho" in her image. When her work is read through the lens of these previous readings, it becomes clearer that, despite her commercial success, she, too, is an unruly commodity. She deconstructs the binary central to hip hop gender codes, yet her visible use of the terms of hip hop commodification keeps this subversive work marketable. Joan Morgan critiques Da Brat, along with Lil' Kim and Foxy Brown, for succumbing to stereotypes as "hypersexed... hoochie mamas" ("Bad Girls" 76). Morgan cautions, "Marketing yourself as a I'm-a-nasty-little-freak-brave-enough-to-talk-about-it will be a very risky thing for Black women" (134). I believe that Da Brat's strategy is more complex than Morgan gives her credit for.[33] Audiences looking for a critique of the "nasty-little-freak" image will find it, but she codes her critique in a subtle way that does not alienate consumers of the "ho" stereotype. Perhaps this strategy is too risky, as few critics perceive the ways in which she signifies on their judgments. Yet this double-edged promotion has also pushed Da Brat's message to the center of hip hop culture.

- Sony Music says of her newest album,

Unrestricted (2000),

"Though Da Brat's peeling the layers off to reveal both her beauty and

her talent, there's still plenty of rawness to draw fans back.... She's

the perfect female MC still coming on hardcore while remaining undeniably

feminine" (<http://www.sonymusic.com/artists/DaBrat/>).[34] This interpretation reflects no

sense of contradiction between "feminine" and "hardcore," missing the

tension between the roles of "gangsta" and "ho." It also takes Da Brat's

image literally, suggesting that Unrestricted "uncovers" the

essence of

Da Brat more than her earlier work since she shows more skin than "the

big-shirts-baggy-jeans-and-braids-look" she was once known for. I would

argue, in contrast, that the image on Unrestricted is

self-consciously

artificial. Particularly when compared to the covers of Da Brat's

previous two albums, Funkdafied (1994) and

Anuthatantrum (1996)--both of

which feature multiple pictures of the artist in jeans, leather jackets,

loose-fitting suits, and jerseys--the cover of Unrestricted

appears staged, and the quasi-nudity takes on the effect of masquerade,

as in Ursula Rucker's "The Unlocking"

(<http://dabratdirect.com/>).

Cover art from Da Brat's Unrestricted - Rather than "peeling the layers off" of Da Brat, the album cover for Unrestricted veils, obscures, and teases, layering familiar components of both "gangsta" and "ho" mythology. What appears to be a photograph of the performer unclothed is itself almost completely covered with fragments of other pictures of Da Brat, spliced together to fill in the shape of her body. This body, rather than being naked, is constructed from heterogeneous images that jar against each other, confuse, and render it incoherent as a body. Where there should be an exposed breast, there is part of a red down jacket. Where there should be genitals, a tattooed upper arm. The composite image has five faces, located on an arm, a shoulder, a leg, a hip, and on top of the shoulders. Da Brat, according to this image, embodies multiple images, feathers, leather, down, and denim. The body that one expects to reflect feminine beauty and heterosexual desire turns out to be grotesque in its excess: too many images, too many bodies. Like Bryant's Chaka Khan, this body is too much, too artificial to be desirable. Since this is the cover of an album for sale, the female body is quite literally a commodity, but this body is self-reflexively (re)produced, edited, copied, and objectified. I read this image, then, as a critique of the expectation that female rap stars present themselves as desirable objects for male consumption. It is a more subtle version of the message offered in Jones's "Blood" and "your revolution." Da Brat cannot be contained by the commodified image that marks--and markets--her body.

- Significantly, the back cover of Unrestricted

challenges

the "undeniably feminine" image. As the front cover manipulates and

defamiliarizes the "ho" image, the back cover reflects the "gangsta,"

complete with fedora, tough stare, and long fur-collared topcoat. But can

she be both? What would it mean to belong to both schools, to pose both

for and as a man? Several songs on the album interrogate this tension.[35] The first song, "We Ready," could

court sex or a fight in the chorus "anybody who wants some / Nigga we

ready for you."[36] The fact that the

male voices of Jermaine Dupri and Lil Jon join Da Brat's in this chorus

makes "we ready" potentially signify as both a gang's rallying cry and a

declaration of mutual passion. This song also presents Da Brat's image as

artificially constructed and excessive, though the list of objects that

render the rapper desirable remains consistent with familiar hip hop

iconography:

This image is a hip hop cliché. The Jeep and the body function as metonymies for each other as the image bumps, blinks, and sparkles. The object of desire is thus both Jeep and woman; headlights and rims blend with ears and wrists. As this image fuses body and machine, it also fuses "gangsta" and "ho," including Glocks [guns] in the list of jewelry and car parts. The net effect is overwhelming, "devastating," "baking the fuck out of me," perhaps parodying the effects of men's desire for both cars and women. Ironically, this Jeep is so crowded with friends and speakers that there is no room for sex in the backseat or in the trunk. Excess, here, makes realization of this typecast desire untenable. So audiences will not find Da Brat, either, "in the / backseat of a Jeep with LL / hard as hell / doin' it & doin' it & doin' it well" (Jones 32). Although Da Brat does not reject the Jeep, the Glock, or the gold chain, she employs them against heterosexist convention.They say they like the way the system pound in my jeep

I got two twelve's that bump from wall to wall

So loud that the headlights blink on and off

I laugh when people watch I don't stop I shine

It's attractive to motherfuckers that love to grind

I sparkle from the rims to the chain to the watch

To the rings to the ears to the wrists to the Glocks

To the parts in the braids

Shorties that stop to watch throw on the shades

Cause Da Brat got gleam for days

Sunroof open let the sun shine in

Baking the fuck out of me and all my friends

In the backseat, stay in the front

Ain't no room in the trunk

Just a devastating woofer that bump - Another song on Unrestricted, "Runnin' Outta Time," narrates from the perspective of a woman whose lover is cheating on her. This stereotypical "tragedy" provides the occasion for the narrator to assert her own mastery ("I'm a master at the craft cause I roll with some master thugs / Laughin' as I pass you up"), and this mastery is also coded as both "gangsta" ("I keep a chip on my shoulder / 44 in the holster bulletproof vest under my clothes") and "ho." Indeed, just a few lines before she discloses the "44": "Ain't nothin' them other hoes could do / Cause I molded you / To fit properly was inside of me / When you're strokin' them / You're thinkin' of riding me / And most of them hopin' to slide with me / Cause I'm a ferocious ho." These lines do several things. As with Rucker's "The Unlocking," these lines could be interpreted as rescripting "ho" to include agency, authority, and ownership. Since she "molded" her lover, he becomes her property, fitting "properly" inside of her. It is her authority that makes their sex "proper." Moreover, Da Brat couples "ho" with "ferocious," coding whore as gangster, giving the woman control over her own sexuality. She is her own pimp and her own protector. One other significant effect of these lines is that the "them" who wants to "slide" with the woman is syntactically the same "them" that her lover is stroking, subverting any strictly hetero-interpretation. This song also features Kelly Price singing with Da Brat. As the two voices weave together in the chorus, both women become the "I" who is "wonderin' where you've been sleepin'," complicating the interpretation of "we" in the title line, "We've been runnin' out of time." Is it the two women or a woman and a man?

- Da Brat frequently distances sex from a hetero-imperative throughout the album by declaring desire for (and desirableness to) both men and women. In "Breve On Em," she poses a question about herself: "Is she is or is she ain't a dyke?" This unanswered question adds to the intrigue surrounding her identity. Moreover, she sings it with a pause before "a dyke," giving the word extra emphasis and allowing the question "is she is or is she ain't" to be heard without any designated referent. Throughout Unrestricted, Da Brat plays with expectations and stereotypes. The album ultimately constructs an image whose power and desirability lies in its fluidity, its contradictions, and its uncertainty. Although she borrows familiar iconography, her composite identity, I would argue, is incommensurable with any singular types. In this way, the image others critique as succumbing to a stereotype also stages a resistance against binary criteria for judging women in hip hop.

- The key to Da Brat's resistance is excess, and her work has been overtly excessive for years. This excess establishes her distance from the image that she overdoes and reflects a keen sense of awareness and, often, irony. For instance, on Anuthatantrum, "Just A Little Bit More" satirizes "gangsta"-style posturing. The lines "Pop a nigga like a pimple keep it simple enough / Make em wonder what the fuck happened leavin em stuffed / Get that ass kicked fast quick in a hurry" render gangsta-style violence absurd and unchallenging, comparing gun shots to juvenile pimple-popping.[37] The redundancy in the phrase "fast quick in a hurry" suggests both excess and lack of drama. Rather than choreographing a drawn-out display of violence, Da Brat undermines the obsession with violence and gets past the ass-kicking hastily to move on to other lines. Similarly, the lines, "Fuck over the dough and die / Pick your casket if you feel that you gone try some shit / no nigga ever lasted past the first attempt / I leave em baffled and gaffle em all of they keys / Then dispense to my niggas like Sony distributing LP's" deprive gangsta-style violence of skill, deliberation, and suspense. "Fuck over the dough and die" erases the killing process, and dispensing the spoils "like Sony LP's" parodies the commercialization of gangsta rap. Clues to the deception and excess Da Brat builds into this song appear in lines like "It's too much, too lil, too late for you to come up / Be deceived if ya wanna be foolish this bad mandate bitch is / true to the shit." So if listeners choose to be deceived they are "foolish," missing the mandate and the true "shit" that Da Brat has to offer. She also reacts to the possibility of misinterpretation in the line "You felt the fist of fury when you envisioned that I was comin," linking the misperception of her sexual pleasure to violence. As with Bryant's "Ode to Chaka Khan," the objectified image of the woman "coming" is a masquerade that, at crucial moments, erupts to reveal the "true shit," the fist of fury that undermines it. Even if this rap is "too much" and listeners do not clearly hear Da Brat's mandate, they should certainly feel punched, made a fool of, and deceived.

- Jones invokes Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit" in the following

lines from "Blood":

Jones thus positions her work in relationship to Holiday and her precursor's representations of Black bodies: representations from "not-so-long ago" that are still difficult to get a "hold" on. It seems that shoes could not contain the blood of the lynched bodies or of the "strange fruit" that Holiday planted, either. Billie, too, deployed contradiction and dissonance between words and music in order to exceed the categories by which white culture attempted to contain her.[38] Feminist rappers contribute to a genealogy of African American women whose music has defied stereotypical expectations. African American arts have a long legacy of exceeding genres and employing double-edged communication, which indicates that the slave has always somehow escaped the master's framework, overflowed his shoes (to continue with the Nike metaphor). Contemporary feminists, like Jones, Da Brat, Rucker, and Bryant, (re)construct this narrative contest in the framework of today's master's tools: postmodern media, consumer capitalism, and expectations (fueled by MTV and the like) that women artists of color must make a spectacle of their bodies. While Holiday worked within and against the "tragic mulatta" model ascribed to her by audiences, the contemporary artists work within and against media portrayals of hip hop "hos" and "gangstas."[39]none of them [shoes] can hold the blood

that coagulated not-so-long ago

in the lower extremities

of brown-skinned corpses strung up from trees

like drying figs

or hanging potpourri

to sweeten scenes of Southern Gallantry (12) - These artists capture audiences accustomed to racist and misogynist images by employing them in destabilizing ways. Rucker plays along with the "ho" myth but counters misogyny by endowing her whore with authority, mastery, and power over the construction of her own image. She defeats the gender binary within hip hop culture, not just by occupying both poles as Da Brat does, but by deflating the power of the masculine. Bryant highlights the absurdity, the artificiality, and the contradictions behind the sexualized female ideal, which turns out to be grotesque if materially realized. Chaka Khan is alluring as an unreal "ho," but explosive and undesirable as an embodied presence. And finally, Jones takes on different identifications only to move past them; her fluidity resists containment within any singular codes. All three artists ultimately exceed the hip hop frameworks that they interrogate.

- In contrast, Da Brat's covert critique is internal to

hip hop marketing. She molds her image to be recognizable within the

stereotypical gender codes of an exhibitionist "ho" and a gun-toting

"gangsta"; but by fusing the two in one body, she deconstructs the binary

assumed to be at their foundation. Each pole is undermined as a result: a

whore cannot be a whore, or an object of others' sexual mastery, if she

is also a pimp and a gangster. Contradiction and excess baffle the

listener attuned to "gangsta"/"ho" imagery. These artists' political

statements put in dialogue divergent interpretations that contest each

other as well as pre-conceived assumptions: Da Brat is and is not a "boy

toy"; Jones is and is not a stereotypical urban consumer. They work

within predictable "criteria of intelligibility" to expose the faults

behind these assumptions. Rather than creating new images, which would be

susceptible to appropriation or to becoming exclusive in their own right,

they reveal how images themselves are incomplete and fail to capture

the complexity of identity. As in the following lines from Bryant's "Ode

to Chaka Khan," audiences rebound off the "so-called black-faced bimbo,"

the image which "broke down" "beyond image" in the excessive raps of

"wailing" feminists.

if she rushes in deep · my well · like poetry · like flush

like semen · like spit · like your bloodied face ·

reboundin' · one mo time · off the blows · of a

so-called · black-faced bimbo · broke down ·

from wailin' · nu blues · broke down · from wailin'

· nu news · broke down · from wailin' out ·

beyond image · to me · can't be music? - "Can't be music?" The effect is a playful, ambivalent,

multi-grooved process that leads audiences to question each new

impression they arrive at. This open-ended process is the strategy I

offer as a way of making powerful feminist theories that do not master.

Da Brat: "Is she is, or is she ain't...?" Rucker: "Tell me what, what's

my name?" Jones: "you be the needle on my record skippin' / needle on my

record skippin' / needle on my record skippin'..." (28).[40] Audiences move from image to image, repeat,

rebound, never certain of anything but the process of deception and the

foolishness of any one image.

Department of English

James Madison University

bostsm@jmu.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2001 SUZANNE BOST. READERS MAY USE PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTIONS MAY USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE. FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO PROJECT MUSE, THE ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

1. As I have discussed in an article on Michelle Cliff in African American Review 32 (Winter 1998), the expressions of marginalized groups often resemble postmodern practices, since both emerge from a position of decenteredness and suspicion towards the processes of signification. I do not think it is entirely coincidental that postmodernism became popular in the United States at the same time that multiculturalism brought increased attention to the literary traditions and language practices of marginalized peoples. It would be anachronistic and Eurocentric to claim these multi-layered and ironical expressions as exclusively postmodern since these types of expressions have been significant to "multicultural" Americans for over a century, at least.

2. Yo-Yo (who created the Intelligent Black Women's Coalition), MC Lyte, and Queen Latifah are the best-known rappers who assert images of strong, independent women. The artists I analyze, however, present a more complex relationship between feminist resistance and dominant images.

3. I am using "hip hop" to describe the culture associated with contemporary African American urban youth identity, including rap music, fashion, breakdancing, graffiti art, and signifying.

4. For instance, the words "freedom," "woman," and "man" were denied or qualified when used to apply to Black Americans during slavery. Another example of the relationship between African Americans and the English language is the devaluation of "black" as a symbol.

5. Da Brat has fans who are not necessarily interested in gender critique or in female MC's, while Yo-Yo, Queen Latifah, and MC Lyte probably have greater appeal among those specifically interested in gender issues.

6. Da Brat asserts her own mastery and assumes an authoritative posture in songs like "Lyrical Molestation," ("When Da Brat is in the area your shit ain't safe") and an early hit from Funkdafied (1994), "da shit ya can't fuc wit" ("B-R-A-T, the new lady / with this shit you can't fuck me"). She also claims to be desired by everyone: in "Runnin' Out of Time," she asserts that "most of them hopin' to slide with me," and in "At the Club," a man's girlfriend threatens to "kick the shit out of" him for staring at Da Brat rather than at her. Such lyrics demand that audiences take her seriously.

7. According to David Foster Wallace, "not only is a serious rap serious poetry, but, in terms of the size of its audience, its potency in the Great U.S. Market, its power to spur and to authorize the artistic endeavor of a discouraged and malschooled young urban culture we've been encouraged sadly to write off, it's quite possibly the most important stuff happening in American poetry today" (Costello and Wallace 99-100).

8. See Gates's much-quoted study, The Signifying Monkey, for an elaboration of signifyin(g) and repetition with a difference.

9. David Foster Wallace calls rap a "Closed Show," inaccessible to "highbrow upscale whites" (Costello and Wallace 23). In the face of globalized/postnational commodification, hip hop vernacular presents a shoring up of black nationality resistant to outside appropriation. Despite this potential insularity, I would emphasize the multiple meanings allowed by hip hop as living, public, communal productions.

10. In an interview with Lisa Kennedy, Queen Latifah says, "I'm not a feminist. I'm not making my records for girls. I made Ladies First for ladies and men. For guys to understand and for ladies to be proud of.... I'm just a proud black woman. I don't need to be labeled" (DiPrima, "Beat the Rap" 82). My own definition of feminism does include men, considerations of racial difference, and pride. In an October, 2000 Ms. article, Sarah Jones, too, is cautious about her assuming the label "feminist," though she ultimately embraces feminism: "Jones hesitates when asked if she calls herself a feminist. 'That's a good question,' she says. 'I don't know if I do. I call myself a womanist. No, that's not true. I'm a feminist and a womanist'" (Block 84). This qualified response reflects Jones's resistance to labels as well as the tentative relationship between African American gender issues and feminism. I understand that the name "feminist" carries a history of exclusivity but believe that the best way to challenge such exclusion is to expand the term from within.

11. I agree with bell hooks's assessment that "a central motivation for highlighting gangsta rap continues to be the sensationalist drama of demonizing black youth culture in general and the contributions of young black men in particular. It's a contemporary remake of Birth of a Nation--only this time we are encouraged to believe it is not just vulnerable white womanhood that risks destruction by black hands, but everyone" (Outlaw Culture 115).

12. In brief: Judith Butler theorizes how we perceive bodies through the discourses of the dominant culture. The body, as we know it, is "orchestrated through regulatory schemas that produce intelligible morphological possibilities. These regulatory schemas are not timeless structures, but historically revisable criteria of intelligibility which produce and vanquish bodies that matter" (14). And such criteria are most effectively "revised" and "destabilized" "through the reiteration of norms"; "in the very process of repetition... [lies] the possibility to put the consolidation of the norms... into a potentially productive crisis" (10). Butler's theory resonates powerfully with feminist hip hop politics. Cultures offer limited "morphological" possibilities for what counts as an intelligible human body. But it is not just through the work of postmodern theoreticians that we observe cultural criteria "vanquishing" bodies that matter. Within African American history we can find concrete examples of this model: slaves became known as slaves by virtue of the branding iron, the master's paperwork, and the meanings attributed by white Americans to their black skin. In the case of African American women, in particular, Hazel Carby has shown how antebellum literature created images of Black women as overtly sexual bodies in order to justify the masters' rapes of their female slaves. Discourses of nineteenth-century womanhood excluded Black women from virtuous humanity and represented them as capital and breeders of capital. Slave women were confined by this objectification, often kept exclusively for the purpose of sex--their bodies seen as sites for the master's pleasure and the reproduction of slave babies.

The racialized misogyny produced during slavery still shapes public perceptions of African American women. When bell hooks tried to reclaim "the female body as a site of power and possibility," her openness to sexuality was perceived by Tad Friend of Esquire magazine as "pro-sex," and in his 1994 interview, he describes hooks as a "do-me" feminist (Outlaw Culture 75). hooks says of this interview: Friend "continues the racist/sexist representation of Black women as the oversexed 'hot pussies'" (76). Her liberated identity and her feminist philosophies exceed the "criteria of intelligibility" that are currently available to the dominant culture, which reduces hooks's body politics to the racist and misogynist mythologies left from slavery. hattie gossett also addresses the limiting vocabulary available to the dominant culture for labeling Black women's sexual bodies in her poem, "is it true what they say about colored pussy?" (1989). She invokes racist and misogynist constructions of women of color's sexuality as a stereotype too dehumanizing to name directly, but even by posing it as a question, she employs it. Indeed, she refuses to leave it unsaid: "don't be trying to act like... you haven't heard those stories about colored pussy so stop pretending you haven't." It might seem counterproductive to repeat this objectifying rhetoric, but gossett invokes and questions the myths surrounding "colored pussy" in order to challenge the historical misogyny directly. She concludes the poem by asserting the power to reconstitute the dominant "morphology" imposed upon Black women: "colored pussies are yet un-named energies whose power for lighting up the world is beyond all known measure," locating "colored pussies" outside of any name (including "colored pussies") (Pleasure and Danger 411-12). The contradiction built within this sentence, using a deleterious name to describe an unnameable energy, is an important strategy used by many African American feminists to highlight their alienation within dominant frameworks and to contest their simultaneous oppressions (see The Combahee River Collective's 1977 "A Black Feminist Statement" for a theorization of the term "simultaneous oppression" as applied to women of color.). One could critique gossett for failing to name the alternative energy that exceeds "colored pussy," yet by keeping this power "un-named" and "beyond measure," she rejects the rules and measures of the dominant discourse and avoids the possibility of containment within that discourse. Hip hop-style feminisms often employ this same strategy: invoking the negative images perpetuated by history while undermining them. Audre Lorde wrote in 1979 that "the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house" (99). What I am most interested in are the strategies that disarm the master by taking his tools and breaking them so that he may never again use them to commit violence. This strategy allows one to contest the master and his terms by exposing their incompleteness in representing African American "morphologies."

13. For instance, Kolawole writes that "Latifah's stance has led to rumours about her sexuality. She has on several occasions stated that she is heterosexual, but her 'unsexy image,' along with her views, appear to be too much for the male-dominated world of rap to consume, with consequences for her sales" (12).

14. Tricia Rose reclaims some feminist agency for Salt 'N Pepa by describing their image as "irreverence toward the morally-based sexual constrictions placed on them as women.... Their video ["Shake Your Thang"] speaks to black women, calls for open, public displays of female expression, assumes a community-based support for their freedom, and focuses directly on the sexual desirability and beauty of black women's bodies" (124-5). Rose's optimism hinges on Salt 'N Pepa's focus on their butts, which she regards as "a rejection of the aesthetic hierarchy in American culture that marginalizes black women" (125). It is a pose staged against the cult of ultra-thin white femininity. Yet the pose still revolves around an assumed spectator who desires women's butts.

15. Joan Morgan's description of hip hop feminism follows this logic of hetero-gender binaries in When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: My Life as a Hip-Hop Feminist (1999). In her defense of "the f-word," she reduces feminism to heterosexual desire--"So, my brotha, if loving y'all fiercely and wanting it back makes me a feminist then I'm a feminist"--and celebrates her political assertiveness as having "'a bigger dick than most niggas I know'" (Chickenheads 44-45, 46). Within this framework, women in hip hop must act manly and/or act for men's benefit.

16. When Houston A. Baker, Jr. assesses the role of women in rap in the face of this centering of masculinity, he concludes that "there are successful black women rappers, but proportionally they represent a cluster of stars in a vast constellation. Two indispensable aspects of the form--its blackness and its youthful maleness--seem to occasion a refusal of general, serious, and nuanced recognition" (62). In this view, the "maleness" of rap eclipses the presence of female rappers, relegates them to just one small corner of the genre. Evidently, according to Baker's definition, women do not define or influence the "vast constellation" as a whole. Rather than "refusing" to offer serious recognition to the indispensable maleness of rap (which Baker accuses others of doing), my study acknowledges the ways in which female artists have had to negotiate this maleness. I would go further, though, to argue that this very maleness has been contested, nuanced, and shaped by the presence of female (and often feminist) authority from the start.

17. Potter suggests that by staging the constructedness and "unreality" of images, hip hop produces its own counter-realities: "Hip hop stages the difference of blackness, and its staging is both the Signifyin(g) of its constructedness and the sites of its production of the authentic. In this staging, hip hop... exchang[es] the unreal 'real' for the 'real' production of the constructed..... And... the insurrectionary aspect of this 'act' has been that it has forced Euro-American culture to take stock of its own costumes, lingo, and poses" (122). As in Butler's theory of gender performance, the self-conscious, often parodic constructions within hip hop "stage" the constructedness of race, in general, and denaturalize dominant racial images.

18. "E.R.A." appears on a 1997 King Britt album, When the Funk Hits the Fan; "Return to Innocence Lost" appears on Things Fall Apart, a 1999 album by the popular hip hop band, The Roots. Both pieces critique a lack of support and appreciation for women as mothers and lovers. "E.R.A." celebrates the power and beauty of women--"soldiers" and "flowers," "revolutionary, Isis, Saint, priestess,... wife, nature, mujer"--calling on a "strengthening presence already ages fortified by years been denied, set aside." "Return to Innocence Lost" tells the story of an alcoholic father who cheats on his wife--"soiling Mommy's sheets with... / Sweet... talk shit, / Cookie's cheap lipstick, / Hairgrease, sperm, and jezebel juice / To hell with the good news that... / He was a father for the first time"--and whose negative influence leads his son to become his "twin in addiction," a gangster, shot and killed on Christmas.

19. Sarah Jones has a similar strategy. She recorded "Blood" on the popular hip hop Lyricist Lounge album, and her first performance piece, Surface Transit, directly invokes hip hop culture and was performed during the 2000 Hip Hop Theater Festival in New York. Through these venues, she has gained visibility within hip hop culture. Loyal fans find in her new performance, Women Can't Wait, however, few references to hip hop, an overtly feminist message, or an international frame of reference.

20. Significantly, we see no money change hands, undermining the whore's status as commodity.

21. All Rucker lyrics I use in this paper are my own transcription of her recordings.

22. A dissonance between words and music is a defining feature of rap. David Foster Wallace argues that "the coldly manufactured, self-consciously derivative sound carpet of samples over which the rapper and DJ declaim serves to focus listeners' creative attention on the complex and human lyrics themselves" (Costello and Wallace 97). The music that forms an apparently insignificant background does more than highlight a complex rap. Rather, as with jazz singing, the melody fabricated in hip hop by DJ and sound machine modifies the tone, and thus the meaning, of the MC's rap. Often rappers borrow familiar melodies--as in Run DMC's sampling of the theme from Exodus in a recent hit, "Crown Royal"--to contextualize their message. In the raps I am analyzing, the tension is far more subtle and thus demands more careful listening. As with much hip hop, then, the critical political message is missed (or deliberately hidden, perhaps) without close study. Nearly inaudible background noises, shifts in tempo, and ruptures in otherwise numbingly repetitive bass-driven melodies establish a relationship between the song and its lyrics that often runs counter to a strictly literal reading of the words. These seemingly unmasterful and insignificant sound carpets establish distance between artist and lyrics and self-reflexively remind listeners that they are being drawn into an artistic manipulation.

23. All Dana Bryant lyrics in this paper are taken from the CD jacket for Wishing from the Top.

24. In the chapter entitled "Slave and Mistress" in Reconstructing Womanhood, Hazel Carby discusses nineteenth-century rhetoric designed to blame female slaves for their own rapes and to portray slave masters as unwilling victims of their slaves' sexual manipulations.

25. While anti-foundationalists like Butler might question our ability to perceive the matter beyond the cultural inscription, Bryant pushes it in our faces.

26. Even ABC's Nightline briefly featured Jones speaking about hip hop in a September, 2000 series, "Hip Hop" (<http://abcnews.go.com/onair/Nightline/nl000906_Hip_Hop_feature.html>).

27. Throughout "Metaphor Play," Jones alludes to a sexual relationship with ungendered metaphors, such as, "if my day is a subway ride / then your smile is any empty car / on the express train to my house" (Jones 27).

28. My analysis of Surface Transit is based on a June 30, 2000 performance at PS 122 in New York.

29. Significantly, Keysha is unable to recognize the original sources for music sampled by contemporary hip hop artists Biggie Smalls and KRS-One. She falsely assumes the hip hop sources to be original and effaces their pre-hip hop contexts. This naïveté could be a self-reflexive jab at Jones's own status as a young, post-hip hop artist.

30. Musical commentary for "Blood" is based on the recording found on Lyricist Lounge, Volume One (1998). Lyrics for "Blood" are quoted from Jones's chapbook, your revolution (1998).

31. David Foster Wallace offers an explanation for this stereotype of underprivileged African Americans as excessive consumers: "Seeing as op-/apposite their grinding poverty and dependence on bureaucracies only the contrasts of 2-D Dynasty image, superrich athletes and performers, and the drug and crime executives for whom visible affluence is part of the job description--such a culture in such a place and time might well be excused for equating success and accomplishment directly with income, display, prestige" (Costello and Wallace 119). Nightline reinforces the negative image of hip hop materialism by drawing attention to Russell Simmons's and L.L. Cool J's conspicuous display of designer goods and the unreasonable consumer standards that these leaders thus create (<http://abcnews.go.com/onair/Nightline/nl000906_Hip_Hop_feature.html>).

32. Lyrics from <http://lyrics.astraweb.com>.

33. I think Da Brat is also more complex than Foxy Brown, Lil' Kim, and so-called "porno rappers," who market themselves exclusively as sexual commodities. We never see Foxy Brown and Lil' Kim without their "ho"-styled mask or attire, but Da Brat presents a different story, one that is more aggressive and styled as self-authored.

34. This album title echoes Millie Jackson (perhaps the first female rapper), who joins Da Brat on the album's "Intro" with an explicit rap on the feminist assertion, "no means no": "Tell the motherfucker 'no' when you don't feel like screwin!" Unrestricted thus frames Da Brat's raps in the context of her oft censored (and censured) foremother. Jackson recorded several rap songs in the late 1970s, including "All the Way Lover" and "The Rap," in which she gives women spoken-word sexual advice over heavily-rhythmed "sound carpets." In a 1982 live recording of "Lovers and Girlfriends," Jackson raps that she was rapping long before it became a money-making industry: "It seems just about the time I stopped rapping, everybody else started. I said, now, I started this shit, I think it's time that I go back and make some more money off of it."

35. Lyrics for "We Ready" and "Back Up" come from Astraweb lyrics, <http://lyrics.astraweb.com>; the lyrics for "Runnin' Outta Time" are borrowed from <http://www.lyrics.co.nz/dabrat>.