The Baudrillardian Symbolic, 9/11, and the War of Good and Evil

Bradley ButterfieldUniversity of Wisconsin, La Crosse

butterfi.brad@uwlax.edu

© 2002 Bradley Butterfield.

All rights reserved.

- From Princess Diana to 9/11, Jean Baudrillard has been the prophet of the postmodern media spectacle, the hyperreal event. In the 1970s and 80s, our collective fascination with things like car crashes, dead celebrities, terrorists and hostages was a major theme in Baudrillard's work on the symbolic and symbolic exchange, and in his post-9/11 "L'Esprit du Terrorisme," he has taken it upon himself to decipher terrorism's symbolic message. He does so in the wake of such scathing critiques as Douglas Kellner's Jean Baudrillard: From Marxism to Postmodernism and Beyond (1989), which attacked Baudrillard's theory as "an imaginary construct which tries to seduce the world to become as theory wants it to be, to follow the scenario scripted in the theory" (178). Did Baudrillard seduce 9/11 into being--is he terrorism's theoretical guru?--or did he merely anticipate and describe in advance the event's profound seductiveness?

-

To Kellner and other critics, Baudrillard's theory of postmodernity is a

political as well as an intellectual failure:

Losing critical energy and growing apathetic himself, he ascribes apathy and inertia to the universe. Imploding into entropy, Baudrillard attributes implosion and entropy to the experience of (post) modernity. (180)

To be sure, Baudrillard's scripts and scenarios have always been concerned with the implosion of the global capitalist system. But while Baudrillard's tone at the end of "L'Esprit du Terrorisme" can certainly be called apathetic--"there is no solution to this extreme situation--certainly not war"--he does not suggest that there are no forces in the universe capable of mounting at least a challenge to the system and its sponsors (18).

- As in Symbolic Exchange and Death (1976) and Simulacra and Simulations (1981), Baudrillard again suggests that terrorism is one such force, and that it functions according to the rule of symbolic exchange. Terrorism can be carried out in theoretical/aesthetic terms, the terms Baudrillard would obviously prefer, or in real terms, that is, involving the real deaths of real people, a misfortune Baudrillard warns against.[2] Though he states clearly "I am a terrorist and nihilist in theory as the others are with their weapons," he is characteristically ambivalent in relation to "real" terrorism, since the real is always in question, and perhaps also because ambivalence is Baudrillard's own brand of theoretical terrorism (Simulacra 163). One moment of his thought is the utopian dream of radicality and reversal, a revolution of symbolic exchange against the system, and the other moment is one of profound pessimism: "The system...has the power to pour everything, including what denies it, into indifference."

- In Simulacra and Simulations (1981), Baudrillard wrote that systemic nihilism and the mass media are to blame for the postmodern human condition, which he describes as a combination of "fascination," "melancholy," and "indifference." Against the system and its passive nihilism, Baudrillard proffers his own brand of what might be termed active nihilism, a praxis that includes theoretical and aesthetic "terrorism," but not, in the end, the bloody acts of actual violence his theory accounts for. The terrorist acts of 9/11, as his theory predicted, were destined to be absorbed by the system's own narrative, neutralized by the very mass media they sought to exploit.

-

In "L'Esprit," Baudrillard nevertheless attempts to explain again the

logic, the spirit, of terrorism and to account for its power. Two of the

three letters written to Harper's Magazine after its February

2002 printing of "L'Esprit" would, predictably, take Baudrillard to be an

apologist for the terrorists' means and ends. Edward B. Schlesinger and

Sarah A. Wersan of Santa Barbara, California, write:

Embedded in Jean Baudrillard's almost incomprehensible prose is the shocking assertion that terrorism is justifiable, that the threat of globalization, as visualized by Baudrillard, justified the World Trade Center attack. (Kelly et al. 4)

Average Harper's readers may be spared blame for not comprehending Baudrillard's theoretical prose, but the point of "L'Esprit" is not that 9/11 was justifiable in any moral sense, but that, as Nietzsche held, true justice must end in its "self-overcoming" (Genealogy 73). Baudrillard explicitly states that "if we hope to understand anything we will need to get beyond Good and Evil" ("L'Esprit" 15). In light of his past writings, I suggest that his unspoken stand on the issue of justice concerning 9/11 would have to be what Nietzsche's would have been: that there is no justice, only forgiveness, and only the strong can forgive. But Baudrillard does not explicitly state this claim, which I see as an implicit conclusion to his thought. Instead he plays the provocateur by laying claim to the terrorists' logic, which was their greatest weapon. If, as Kellner would have it, Baudrillard wants to seduce us into following his script, we must be sure to understand the script well so we can decide how to act on it. The fact that 9/11 was arguably the most potent symbolic event since the crucifixion of Christ has inspired Baudrillard to dress up his old ideas about the symbolic and symbolic exchange. To understand what he means by "symbolic dimension" and "strategic symbolism" in the quotation from "L'Esprit" above, let us consult the origins and uses of the concept of the symbolic in his earlier work.

Baudrillard's Symbolic and Death

-

Baudrillard's theory of the symbolic serves as a response to what he saw

as the metaphysical underpinnings of the Marxist, Freudian and

structuralist traditions. All three, he claims, uphold the fetishization

of the "law of value," a bifurcating, metaphysical projection of the

mind which allows us to measure the worth of things. The law of value

effectively produces "reality" in each system as both its effect and its

alibi. For Marx this reality, this metaphysical claim, was found in the

concept of use value, for Freud it was the unconscious, and for Saussure

it was the signified (and ultimately the referent). According to

Baudrillard, any critical theory in the name of such projected "real"

values ultimately reinforces the fetishized relations it criticizes. He

therefore relocates the law of value within his own Nietzsche-styled

history of the "image"--a term used as a stand-in for all that the words

representation, reproduction, and simulation have in common. In "How the

'True' World Finally Became a Fable: The History of an Error," Nietzsche

outlines in six concise steps the decline of western metaphysics and its

belief in a "True world" of essences, beyond the Imaginary world of

appearances (Portable 485). Baudrillard's four-part history

of the image (commonly referred to as his four orders of simulation)

closely mirrors Nietzsche's history of the "'True' World":

- it [the image] is the reflection of a profound reality;

- it masks and denatures a profound reality;

- it masks the absence of a profound reality;

- it has no relation to any reality whatsoever; it is its own pure simulacrum. (Simulacra 6)

Marx, Freud and Saussure were stuck in the second order, where the critique of appearances was thought to yield a glimpse of a deeper reality. We have since turned from the critique of appearances to the critique of meaning and of reality itself (the third order), and from here can only enter into the fourth order, the hyperreal. This is because we live in profoundly mediated environments, wherein coded images are produced and exchanged far more than material goods, and the more these codes are exchanged throughout the culture, the more erratically their values fluctuate, until at last they can no longer be traced to their origins. Hyperreality thus describes the extreme limit of fetishization, wherein re-presentation eclipses reality. Here the spectacle continues to fascinate, but indifference is the attitude du jour (indifference having long been associated with the postmodern). But Baudrillard's history, it seems, has one more step to take before it completes its circle. Baudrillard imagines that from within the fourth order, where all metaphysical distinctions of value have disappeared, there will emerge a type of postmodern primitivism (I propose to call it), which he outlines in his conceptions of the symbolic and symbolic exchange.

-

Baudrillard's symbolic derives loosely from Mauss's analysis of the

Potlatch, Bataille's theory of expenditure, and a deconstruction

of Lacan's symbolic/real/imaginary triad. For Lacan, the symbolic marks

the adult world of discourse, wherein the subject comes fully into being

as it leaves the narcissistic fantasies of the imaginary order to

recognize, and be recognized by, the other. Entry into the symbolic,

however, also severs the subject from "the real" or material "given,"

which always remains beyond the reach of signification. The symbolic for

Lacan plays a balancing act between the demands of a lost imaginary and a

lost real, while for Baudrillard "the effect of the real is only

ever . . . the structural effect of the disjunction between two terms"

(Symbolic 133). The real and the imaginary are not lost

causes, but rather lost effects of consciousness, and the

symbolic is that within a social exchange which is irreducible to the

real/imaginary dichotomy:

The symbolic is neither a concept, an agency, a category, nor a "structure," but an act of exchange and a social relation which puts an end to the real, which resolves the real, and, at the same time, puts an end to the opposition between the real and the imaginary. (133)

When we enter the Baudrillardian symbolic dimension, the biased distinctions of Western metaphysics--Cause/Effect, Being/Nothingness, Real/Imaginary, Normal/Abnormal, Good/Evil--are to be considered deconstructed, over-come in the French Nietzschean tradition of the aesthetic turn. The symbolic is Baudrillard's trope for the revaluation of all values, jenseits von Gut und Bose, a revolutionary theory for the age of digital reproduction and the generalized aesthetic sphere. In the Baudrillardian symbolic, one hears the echo of Nietzsche's merriment at the end of metaphysics: "pandemonium of all free spirits" (Portable 486). The "death drive" in Baudrillard is therefore not a matter of a repressed instinct (Freud), nor even yet of a universal force within language (Lacan), but of an incipient implosion of "the code," which stands for all terms and forces valued in opposition within the system. In the wake of his implosionary vision Baudrillard hopes will arise, at least in theory, a liberated and continuously creative new set of relations, governed not by semiotic or economic codes, but by the principle of symbolic exchange.

-

In For a Critique of the Political Economy of the

Sign, Baudrillard harkens back to the "primitive" notion of the

symbol as transparent, binding, and potentially brutal in its demands (he

does not qualify the term primitive, and after all it is the model that

is important to him, whether his generalizations are accurate or a

projection of desire[3]). This would-be

dark side of Baudrillard's symbolic stems from what he himself calls a

dangerous allusion to primitive societies in Mauss's illustrations of the

Kula and the Potlatch (Critique 30).

Mauss describes the primitive practice of Potlatch as involving

an agonistic exchange of gifts between two chieftains in which each one

seeks to gain standing for himself and his clan through gift exchange

(Mauss 6). Baudrillard clarifies that

the gift is unique, specified by the people exchanging and the unique moment of the exchange. It is arbitrary [in that it matters little what object is involved], and yet absolutely singular.

As distinct from language, whose material can be disassociated from the subjects speaking it, the material of symbolic exchange, the objects given, are not autonomous, hence not codifiable as signs. (Critique 64-65)

The symbolic value of a gift or of any gesture depends upon the involuntary consciousness of the fact that the consciousness of the other poses a singular challenge to our own. And we cannot not respond to this challenge, once we have received it, because even ignoring someone or something is a way of responding. The gift represents a qualitative measurement of honor or disgrace between two parties and in that sense is symbolic, but it is also symbolic in Baudrillard's other sense, that is, as standing only for itself, as a unique and ineluctable challenge to counter give. It takes a certain amount of Orwellian doublethink to ignore the challenge represented by the other once we have grasped the reciprocal nature of our fates. For Baudrillard's and Mauss's "primitives," events such as the Potlatch involve conspicuous consumption and expenditure, a sumptuous wasting of goods that turns out in the end to be essentially usurious and sumptuary (see Critique 30, Mauss 6).

- Baudrillard formulates the term "prestation" with regard to Mauss

to signify that within our social exchanges which makes us feel obligated

to "an irrational code of social behavior," namely the law of symbolic

exchange (Critique 30, n. 4). This mechanism of social

prestation, says Baudrillard, adheres to every exchange and is fraught

with ambivalence, for in it lies "the value . . . of rivalry and, at the

limit, of class discriminants" (Critique 31). Symbolic

exchange, at some level, always involves an agonistic struggle for

domination and status. Baudrillard does not issue a moral judgment on

the matter of social domination, but rather suggests that symbolic

exchange will continue to haunt our political economies:

Behind all the superstructures of purchase, market, and private property, there is always the mechanism of social prestation which must be recognized in our choice, our accumulation, our manipulation and our consumption of objects. This mechanism of discrimination and prestige is at the very basis of the system of values and of integration into the hierarchical order of society. The Kula and the Potlatch have disappeared, but not their principle. (30)

The symbolic value of commodities--the connotations of wearing a certain brand of basketball shoe or driving a certain car--are seen here as barbaric in the social relations they imply. And so Baudrillard warns in an interview:

If we take to dreaming once more--particularly today--of a world where signs are certain, of a strong "symbolic order," let's be under no illusions. For this order has existed, and it was a brutal hierarchy, since the sign's transparency is indissociably also its cruelty. (Baudrillard Live 50)

One nevertheless senses in this disavowal of the primitive symbolic order, where signs were singular and binding, a hint of admiration, echoing Nietzsche's musings on the cruel but proud days when power was signified outright, and not behind the guises of morality.[4]

-

Despite this transparent warning, in Symbolic Exchange and

Death (1976) Baudrillard went on to sketch several examples of

symbolic exchange in relation to death in today's political economy. The

anagram in Saussure, the Witz in Freud, graffiti in New York, the

Accident in the media are all treated by Baudrillard as symbolic events

wherein death, denied and repressed, poses a challenge to life. From the

standpoint of 9/11, his theory of death in primitive and modern cultures

is most pertinent. Like Foucault, Baudrillard sees the history of Western

culture in terms of a genealogy of discrimination and exclusion:

At the very core of the "rationality" of our culture, however, is an exclusion that precedes every other, more radical than the exclusion of madmen, children or inferior races, an exclusion preceding all these and serving as their model: the exclusion of the dead and of death. (Symbolic 126)

According to Baudrillard, the dead in primitive societies played integral roles in the lives of the living by serving as partners in symbolic exchange. A gift to the dead was believed to yield a return, and by exchanging with the dead through ritual sacrifices, celebrations and feasts, they managed to absorb the rupturing energy of death back into the group. But

there is an irreversible evolution from savage societies to our own: little by little, the dead cease to exist. They are thrown out of the group's symbolic circulation. They are no longer beings with a full role to play, worthy partners in exchange....Today it is not normal to be dead, and this is new. . . . Death is a delinquency, and an incurable deviancy. (126)

Modern Western cultures have largely ceased to exchange with the dead collectively, partly because we no longer believe in their continued existence, and partly because we no longer value that which cannot be accumulated or consumed. The dead have no value by our measurements. We give them nothing and expect nothing from them in return, and yet they remain with us, in our memories, obligating our recognition and response. How do we respond to the symbolic challenge of death and the dead, the challenge they pose to our conscious experience? This is the question of 9/11.

- The primitives, Baudrillard maintains, responded to this challenge collectively through symbolic exchanges with their dead and deities. Their belief in the sign's transparency, its symbolic singularity, can be seen in animistic practices such as voodoo, where the enemy's hair is thought to contain his or her spirit. If the dead are only humans of a different nature, and if the sign is what it stands for, then a symbolic sacrifice to a dead person is every bit as binding as a gift to a living person. The obligation to return is placed upon the dead, and they reciprocate by somehow honoring or benefiting the living. Most Christians believe in and employ this same mechanism when they pray to the resurrected Christ, but even they do not believe that their symbolic gestures are anything but metaphors. We no longer believe in the one to one correspondence of signifier and signified, and we know the loved one is not really contained in the lock of hair. Americans will doubtless commemorate the deaths of those killed on 9/11 as long as our nation exists, but we know that our gifts to the dead are only symbolic, which for us means imaginary.

- Baudrillard's postmodern-primitive symbolic, on the other hand, aimed to obliterate the difference in value between the imaginary and the real, the signifier and the signified, and to expose the metaphysical prejudice at the heart of all such valuations. His wager was that this would be done through aesthetic violence and not real violence, but having erased the difference between the two, there was never any guarantee that others wouldn't take such theoretical "violence" to its literal ends. Graffiti art, scarification and tattooing are just the benign counterparts of true terrorism, which takes ritual sacrifice and initiation to their extremes. Literalists and extremists, fundamentalists of all sorts, find their logic foretold in Baudrillard's references to the primitives. What the terrorists enacted on 9/11 was what Baudrillard would call a symbolic event of the first order, and they were undeniably primitive in their belief that God, the dead, and the living would somehow honor and benefit them in the afterlife. Unable to defeat the U.S. in economic or military terms, they employ the rule of prestation in symbolic exchange with the gift of their own deaths. But Americans are not "primitives"--we do not value death symbolically, but rather only as a subtraction from life. Capitalism's implicit promise, in every ad campaign and marketing strategy, is that to consume is to live. We score up life against death as gain against loss, as if through accumulation we achieve mastery over the qualitative presence of death that haunts life. Our official holidays honoring the dead serve no other function than to encourage consumption.

-

When it comes to actually dealing with death and the dead, even

in public, we do so in private. As Baudrillard points out, "This entails

a considerable difference in enjoyment: we trade with our dead in a kind

of melancholy, while the primitives live with their dead under the

auspices of the ritual and the feast" (134-35). Because we devalue death

and thereby the dead, we view them only as a dreaded caste of

unfortunates, and not as continuing partners in exchange. Ultimately,

however, it is not so much the dead but our own deaths, our negative

doubles, that we insult by denying their value. When we posit death as

the negation of life, we bifurcate our identities and begin a process of

mourning over our own eventual deaths, a process which lasts our whole

lives. The more we devalue our death-imagoes, that is, the greater they

become, until they haunt our every moment, as in Don DeLillo's darkest

comedy, White Noise. This leads us, according to

Baudrillard, to an obsession with death that can be felt in the media

fascination with catastrophes like 9/11. Death "becomes the object of a

perverse desire. Desire invests the very separation of life and death"

(147). Political economy's inability to absorb the rupturing energy of

death is thus compensated by the symbolic yield of the media

catastrophe. In these events we experience an artificial death which

fascinates us, bored as we are by the routine order of the system and the

"natural" death it prescribes for us. Natural death represents an

unnegotiable negation of life and the tedious certainty of an unwanted

end. It therefore inspires insurrection, until "reason itself is

pursued by the hope of a universal revolt against its own norms and

privileges" (162). The terrorist spectacle is an example of such a

revolt, in which death gains symbolic distinction and becomes more than

simply "natural." We may not think we identify with the terrorists'

superstitions about honor in the next life, but in events like 9/11,

Baudrillard would suggest, we nevertheless identify despite ourselves

with both with the terrorists and their victims:

We are all hostages, and that's the secret of hostage-taking, and we are all dreaming, instead of dying stupidly working oneself to the ground, of receiving death and of giving death. Giving and receiving constitute one symbolic act (the symbolic act par excellence), which rids death of all the indifferent negativity it holds for us in the "natural" order of capital. (166)

Violent, artificial death is a symbolic event witnessed collectively. "Technical, non natural and therefore willed (ultimately by the victim him- or herself), death becomes interesting once again since willed death has a meaning" (165). Was 9/11 willed by the victims? Obviously not, and yet, Baudrillard would suggest, in our identification with both the killers and those who died, we ourselves are not so innocent.

Nihilism and Terrorism

Implosion of meaning in the media. Implosion of the social in the masses. Infinite growth of the masses as a function of the acceleration of the system. Energetic impasse. Point of inertia.

--Baudrillard (Simulacra 161)

- Baudrillard's most prescient statements regarding terrorism

and the spirit that motivates it were issued in the 1981 essay "On

Nihilism," which falls at the end of Simulacra and

Simulations. Here he distinguishes the first two great

manifestations of nihilism by placing them parallel to his second and

third orders of simulation. Recall:

- it [the image] is the reflection of a profound reality;

- it masks and denatures a profound reality;

- it masks the absence of a profound reality;

- it has no relation to any reality whatsoever; it is its own pure simulacrum. (6)

The first wave of nihilism occurs in the second order of simulation, and corresponds with the Enlightenment and Romantic revolutions against the order of appearances, "the disenchantment of the world and its abandonment to the violence of interpretation and of history" (Simulacra 160). Nihilism is thus first and foremost, for Baudrillard, the signature of the post-metaphysical philosopher. He thus places Nietzsche's statement that "God is dead" at the center of all modernity, but adds that once the critique of metaphysics has run its course, a new type of nihilism is ushered in. "When God died, there was still Nietzsche to say so," i.e., after God there is Nietzsche, after Nietzsche, only simulation (159). "God is not dead, he has become hyperreal."

-

This second wave of nihilism occurs in the twentieth century and

spans the third and fourth orders of simulation, beginning with

"surrealism, dada, the absurd, and political nihilism" (159), which

sought to reveal the absence of a profound metaphysical reality behind

our representations, and ending in

postmodernity, which is the immense process of the destruction of meaning, equal to the earlier destruction of appearances. He who strikes with meaning is killed by meaning. (161)

After discovering the absence of a profound meaning behind the world of appearances, those who seek the true meaning of things end up impaled on the truth that there is no true meaning to be had. Nietzsche's dilemma. And so Baudrillard boldly declares: "I am a nihilist," and swears himself to the destruction of both appearance and meaning, the first two waves, but also to the destruction of the appearance/meaning dichotomy altogether, the postmodern phase of the second wave. If western culture can now be characterized by Baudrillard's notion of a fourth order simulation society, where simulacra dominate our lives and the faith in a "profound reality" has turned radically agnostic, it is here that one must plant one's (post-) philosophical flag. Rather than take the reactionary approach of a return to metaphysics, Baudrillard affects a nihilistic version of Nietzschean amor fati, accepting the system's melancholy and pushing to its limit the "mode of disappearance" it effects in everything it touches (162). The melancholy in Adorno and Benjamin, holds Baudrillard, already stems from this recognition that dis-enchantment, dis-appearance, the critique of reason itself are all inherent to the system's functionality. But their "dialectic" was already "nostalgic," their melancholy the last healthy pulse of "ressentiment" against the systemization of death, a third order phenomenon. Melancholia today, says Baudrillard, is no longer a matter of disenchantment and demystification: "It is simply disappearance." No longer an affect one can deploy in a critique of the system, it is now the affect of "the brutal disaffection that characterizes our saturated systems."

-

Though Baudrillard does not deny melancholia as our appropriate

Zeitgeist, his implicit suggestion in the essay, which Kellner

neglects, is that the passive nihilism (inertia, entropy, implosion)

produced by the implicitly nihilistic system is the philosophical enemy,

which he means to challenge by means of his own brand of active nihilism:

"What then remains of a possible nihilism in theory? What new scene can

unfold, where nothing and death could be replayed as a

challenge, as a stake?" (159). The system has effectively

absorbed the first two waves of active, critical nihilism into its own

nihilism, and induces a state of stupefied, melancholic indifference

in the "receivers" (we are no longer spectators) of its mass mediations.

Baudrillard's strategy, then, is to push the system faster ("revenge of

speed on inertia"), to the point of its implosion, by writing theory that

is the equivalent of intellectual terrorism (161). All other theory at

this point only "assists in the freezing over of meaning, it assists in

the precession of simulacra and of indifferent forms. The desert grows"

(161). In the desert of the real, no amount of analysis can "resolve the

imperious necessity of checking the system in broad daylight. This, only

terrorism can do" (163). Terrorism, writes Baudrillard,

is the trait of reversion that effaces the remainder, just as a single ironic smile effaces a whole discourse, just as a single flash of denial in a slave effaces all the power and pleasure of the master. The more hegemonic the system, the more the imagination is struck by the smallest of its reversals. The challenge, even infinitesimal, is the image of a chain failure. Only this reversibility without a counterpart is an event today, on the nihilistic and disaffected stage of the political. Only it mobilizes the imaginary.

This is of course what happened on 9/11, as Baudrillard has since pointed out, but Kellner would also likely point out that Baudrillard, having himself wished for 9/11, begins "L'Esprit" by projecting this wish onto the rest of us (180). Our collective complicity in the wish is of course impossible to gauge, but in "On Nihilism" Baudrillard had already confessed his own complicity with nihilistic terrorism in the most carefully calibrated terms:

If being a nihilist, is carrying, to the unbearable limit of hegemonic systems, this radical trait of derision and of violence, this challenge that the system is summoned to answer through its own death, then I am a terrorist and nihilist in theory as the others are with their weapons. Theoretical violence, not truth, is the only recourse left us.

But such a sentiment is utopian. Because it would be beautiful to be a nihilist, if there were still a radicality--as it would be nice to be a terrorist, if death, including that of the terrorist, still had meaning.

Baudrillard gives up on the idea of a radicality in theory, a position of negativity relative to the system, Adorno's position. But he is at his negative dialectical best in this passage, which is a statement of complicity with the utopianism of the terrorist's challenge, as well as a statement of the utmost pessimism regarding the subject's ability to effect a change in the system, which in the end neutralizes every event, no matter how deadly:

The dead are annulled by indifference, that is where terrorism is the involuntary accomplice of the whole system, not politically, but in the accelerated form of indifference that it contributes to imposing. Death no longer has a stage, neither phantasmatic nor political, on which to represent itself, to play itself out, either a ceremonial or a violent one. And this is the victory of the other nihilism, of the other terrorism, that of the system. (Simulacra 163-164)

Did death have a stage on September 11th? Have the dead since been annulled by indifference, caught up in the media's mode of disappearance? Despite the terrorists' successful attempt to put death back on stage in a symbolic exchange with "the system," the majority of Americans have by now assimilated its violence into the broader narrative of a war against terrorism and Evil, one of the many things on TV.

-

The 9/11 attacks have succeeded, as Baudrillard says, in turning

the U.S. into a vengeful police state and in accelerating its attempts to

dominate the world through military force, and this in turn has likely

accelerated the mood of passive nihilism (with its fascination,

melancholy, and indifference). No one can claim that any sort of

progressive politics were served by the terrorists' actions. Baudrillard

certainly does not. And the terrorists weren't even nihilists, they were

fundamentalists, a far cry from Baudrillard's romantic ideal of the

philosopher-terrorist. In "On Nihilism," Baudrillard, like Adorno in the

end, prefers theory as praxis to actual praxis. He concludes not on a

note of cynicism and melancholy, as Kellner reads him, but on a note of

paradoxical idealism:

There is no more hope for meaning. And without a doubt this is a good thing: meaning is mortal. But that on which it has imposed its ephemeral reign, what it hoped to liquidate in order to impose the reign of the Enlightenment, that is, appearances, they are immortal, invulnerable to the nihilism of meaning or of non-meaning itself.

This is where seduction begins. (163-164)

Rather than respond with apathy and indifference to the disappearance of meaning now under way, Baudrillard resurrects the once banished realm of appearances, the aesthetic, in a move beyond the nihilism of meaning/nihilism of non-meaning dichotomy. As Kellner writes: "Like Nietzsche, he wants to derive value from the order of appearances without appeal to a supernatural world, a hinterwelt or a deep reality" (120). Kellner, who apparently thinks a more Nietzschean joyfulness, as opposed to Baudrillard's melancholy, is still preferable at the end of the twentieth century, nevertheless holds to the metaphysics of morality against the aestheticism of the French Nietzscheans. For those who no longer acknowledge a "hinterwelt," however, the idea that we exist in a world of appearances which are irreducible to true essences (like Good and Evil), is not so far fetched. One thus takes the Nietzschean turn, toward the aesthetic, and this, Baudrillard tells us, "is where seduction begins." His later work on this concept in On Seduction need not be elaborated here, but we should note that Rex Butler has shown the concept of seduction in Baudrillard to be an elaboration on the concept of symbolic exchange (71-118). "Symbolic exchange," according to Butler,

is not simply the negation of economic value but rather its limit. It is the thinking of that loss, that relationship to the other, which at once allows exchange, opens it up, and means that it is never complete, never able to account for itself. (81-82)

If seduction is what rules the chasm left by a symbolic exchange between the challenger and the system, what was the direction of the seduction created by 9/11? Were we seduced? Was Baudrillard? Are we being seduced by Baudrillard? Having revisited his perspective on terrorism prior to 9/11--terrorism as the ultimate metaphor, but naïve in its utopianism---let us consider his perspective après le spectacle.

9/11: Morning of the Living Dead

The spectacle of terrorism forces upon us the terrorism of the spectacle.

-- Jean Baudrillard ("L'Esprit" 15)

- In "L'Esprit du Terrorisme," Baudrillard maintains that

the U.S. as lone Superpower conjures its own Other; by dominating the

globe it creates global resistance. Baudrillard's opening gambit--"In

the end, it was they who did it but we who wished it"--means to implicate

us all in a symbolic exchange with 9/11:

It goes well beyond the hatred that the desolate and the exploited--those who ended up on the wrong side of the new world order--feel toward the dominant global power. This malicious desire resides in the hearts of even those who have shared in the spoils. The allergy to absolute order, to absolute power, is universal, and the two towers of the World Trade Center were, precisely because of their identicality, the perfect incarnation of this absolute order. ("L'Esprit" 13)

The twin towers, like the twin political parties in the U.S., represent a balance of power, two forces locked in opposition. But like the Democrats and the Republicans, both towers are virtually identical, and their dualistic logic leaves no room for remainders. People rebel, either secretly or openly, against an airtight system, two towers of power representing the same people in charge, the illusion of difference. Finally someone throws a monkey wrench into the works in the form of four jet airplanes, aimed not only at the symbols of American power, but at the American mass media, which serve to broadcast the terror and violence worldwide. By way of our simulation technologies, the terrorists were able to issue a singular challenge to each American, and it is in this way that the event is properly symbolic in the Baudrillardian sense, as a gift demanding return. This is a common motif in Baudrillard, this moment where simulation society is somehow reversed or revolutionized by the symbolic. By insisting on our unconfessable complicity, the assumption that we all have a soft spot for the underdog and a sore spot for the overdog, especially when the latter is on the brink of dominating the global playpen, Baudrillard further challenges us to answer the challenge of 9/11, to enter the debate at the level of a singular exchange. As individuals, our ability to influence what is done in the name of the U.S. is limited, but as intellectuals, we must ask ourselves: what is the symbolic meaning and effect of the event? An essay exam for the whole nation. The twin towers symbolize corporate globalization, the Pentagon the American military, and both together stand for what Baudrillard calls "the system." The numbers 9-1-1 signal Emergency, and the date marks a number of historical events: the 1989 massacre in Haiti which ousted Aristide; the 1973 overthrow of Allende in Chile; and the 1683 battle of Vienna, where Islam was ultimately defeated by Poland, the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire.[5] But for Baudrillard the symbolic meaning of the event lies not only in its reducibility to such referents, but in its irreducible, singular, and irrevocable challenge to each and every imagination. Doubtless most Americans would deny any complicity with the terrorists on 9/11, but few would deny that it was the most fascinating day of the century, and this fascination, the product of the system, was what the terrorists counted on.

-

Baudrillard demonstrates in this essay that what the terrorists

carried out is indeed one version--the most literal version--of what he

has meant all along by a symbolic death exchange with the system, thus

implicating his own theories as those which explain, and in this sense

further fortify, the symbolic power of terrorism. His instruction manual

continues:

Never attack the system in terms of the balance of power. The balance of power is an imaginary (revolutionary) construct imposed by the system itself, a construct that exists in order to force those who attack it to fight on the battlefield of reality, the system's own terrain. Instead, move the struggle into the symbolic sphere, where defiance, reversion, and one-upmanship are the rule, so that the only way to respond to death is with an equivalent or even greater death. Defy the system with a gift to which it cannot reply except with its own death and its own downfall. . . .

You have to make the enemy lose face. And you'll never achieve that through brute force, by merely eliminating the Other. (16)

Certainly the terrorists' attack on the battlefield of reality was devastating on its own, but their attack on the symbolic battlefield, Baudrillard maintains, was far more devastating in terms of achieving their global aspirations. According to the system's logic, the Other loses when they only kill one of your soldiers and you kill all of theirs, but according to the symbolic logic of the terrorists, the greater the sacrifice, the greater the symbolic honor. "In dealing all the cards to itself, the system forced the Other to change the rules of the game," and under the new rules, the strongest power in the world violently decimating one of the weakest powers at the cost of a single life is not honorable, it is only efficient (14). Baudrillard, scandalous as ever, hands the symbolic victory of the war on terror to the terrorists, all but crediting them with recent economic, political, and psychological "recessions" in the West, and with the fact that "deregulation has ended in maximum security, in a level of restriction and constraint equivalent to that found in fundamentalist societies" (18).

-

Since they cannot not report and sensationalize the

event, the media are enlisted in a symbolic exchange that only amplifies

the terrorist's power to terrorize: "The media are part of the event,

they're part of the terror," and so "this terrorist violence is not 'real'

at all. It's worse, in a sense: it's symbolic" (18). The "real"

violence here is thus conducted through the technologies of simulation,

which the terrorists have hijacked for their symbolic ends. Baudrillard's

claim that the symbolic violence was worse and hence more "real" than the

real violence of 9/11 is typically provocative, and another letter to

Harper's takes him on on this score. [6] The argument over which violence was worse, however,

is a dead end, for the question of "the spirit of terrorism" is what is at

stake. What the terrorists count on is that

at the level of images and information, it is impossible to distinguish between the spectacular and the symbolic, impossible to distinguish between crime and repression. And it is this uncontrollable outburst of reversibility that is the veritable victory of terrorism. (18)

- Here again this motif in Baudrillard, where simulation society (the society of the spectacle) is somehow reversed by the symbolic. The reversibility of crime and repression depends upon the media's being seduced into working for the criminals, and in effecting this reversal, the terrorists set off a symbolic-atomic bomb. Their physical violence was aimed at the lives of thousands of American taxpayers, but their symbolic violence was aimed at the symbols of corporate globalization, the American military and perhaps all of Christendom. The agencies of the latter are thus forced into the symbolic arena, and must choose how to respond, what appearances to deploy.

-

In one of the letters to Harper's, Matthew Kelly writes that

"the attack's symbolic wallop is obvious to a toddler," but it is not

just about recognizing that the twin towers and the Pentagon stand for.

Baudrillard means for us also to recognize the primitive symbolic

challenge, the sacrifice, the gift of their own deaths, which demands our

response if we are to save face. One wonders how many Americans would be

willing to sacrifice their lives as a show of support for what the twin

towers and Pentagon symbolize. Baudrillard's point about primitive

symbolism is that the symbol represents a unique and binding challenge, a

gift that must somehow be returned by everyone it affects. How are we,

if we are the U.S., to respond? Our first priority in formulating a

response should be to pose the question the U.S. news media have deemed

too sensitive to ask, namely: why did they do it? On October 7, 2002,

however, Osama bin Laden issued his statement on a videotaped message:

What America is tasting now is something insignificant compared to what we have tasted for scores of years. Our Nation (the Islamic world) has been tasting this humiliation and degradation for more than 80 years. Its sons are killed, its blood is shed, its sanctuaries are attacked and no one hears and no one heeds. Millions of innocent children are being killed as I speak. They are being killed in Iraq without committing any sins. . . . To America, I say only a few words to it and its people. I swear to God, who has elevated the skies without pillars, neither America nor the people who live in it will dream of security before we live it here in Palestine and not before all the infidel armies leave the land of Muhammad peace be upon him. (Andreas 29)

The challenge represented in the gift is clear: "you will not know peace until your military leaves us in peace." This implies a direct question: why is the U.S. military in Arab countries? The answer, of course, is that the U.S. military is there to protect U.S. economic interests, in accordance with its long-held notions of manifest destiny. But U.S. officials do not respond to this implicit question, their response is no response, which of course is a response in itself in symbolic terms. The terrorists count on the likelihood that the U.S. will make a move the world will view as symbolically dishonorable and aesthetically ugly, in relation to their act of defiance, that the harder it strikes back, the worse it will look, and the greater the global resistance. The U.S. can only win on the aesthetico-symbolic plane, where prestation rules, by staying its hand, for there is no courage or beauty in brute force.[7]

-

So does Baudrillard really support terrorism? Do we? Once again

playing the devil's hand, he seduces us to play the avenging angel by

taking a moral stand. But suppose we take the Nietzschean turn, with

Baudrillard, and view the issue in aesthetic terms: can moral goodness

not still succeed in being beautiful if it avoids making metaphysical

claims? When morality is conceived in aesthetic terms, it loses its

guarantee of universality, but not its symbolic force. And yet by

forcing Good on the world, the U.S. only forces Evil to gain strength.

"Terrorism," Baudrillard tells us, "is immoral," but it is a

response to globalization, which is itself immoral. We are therefore immoral ourselves, so if we hope to understand anything we will need to get beyond Good and Evil. . . . In the end, Good cannot vanquish Evil except by declining to be Good, since, in monopolizing global power, it entails a backfire of proportional violence. (Simulacra 15)

The U.S., if it wishes to be Good, can only win, in symbolic terms, by refusing to play, by refusing to be Good. Baudrillard certainly does not proffer war, which he concludes is simply "a continuation of the absence of politics by other means" (18). What he recommends, without naming it, is the forgiveness of debt, the redemption of "Evil."

-

Compare this, then, to Nietzsche's advice, which might have been

directed at a future world power such as the U.S.:

It is not unthinkable that a society might attain such a consciousness of power that it could allow itself the noblest luxury possible to it--letting those who harm it go unpunished. "What are my parasites to me?:" it might say. "May they live and prosper: I am strong enough for that!"

The justice which began with, "everything is dischargeable, everything must be discharged," ends by winking and letting those incapable of discharging their debt go free: it ends, as does every good thing on earth, by overcoming itself. This self-overcoming of justice: one knows the beautiful name it has given itself--mercy; it goes without saying that mercy remains the privilege of the most powerful man, or better, his--beyond the law. (Genealogy 72-73)

The triumph of justice, according to Nietzsche, is its self-overcoming; the most moral is the extra-moral, beyond the war of Good and Evil. If the U.S. had gone with its first name for its new war effort--"Operation Infinite Justice"--would Americans have become more readily aware of the ironic fact that their country had in many ways served injustice in the Middle East for a great many years? Would some have been quicker to see that "infinite justice" can only amount to infinite forgiveness? In this passage, Nietzsche taunts America's wealth and dignity, seducing us with an image of ourselves more befitting our vanity than the image of a vengeful America. Vengeance, ressentiment, always claims morality as its cause, but forgiveness does not have to, because it is a washing away of guilt/debt, because it is a gift. Rather than make claims, it gives them away, which nevertheless poses a challenge to the other to counter-give with a symbolic response. This is for Nietzsche, as for Baudrillard, one would gather, the most beautiful aesthetic/symbolic gesture, an extra-moral gesture, beyond Good and Evil. It is also the only means to peace short of the total annihilation of a virtually invisible enemy. Would a Nietzschean-style forgiveness of debt not entail gestures like the removal of U.S. military bases from the Middle East, the nationalization of Arab oil assets, the discontinuation of all support for dictatorships in the area and around the world, and the promotion of a Palestinian nation? And if such tokens of "forgiveness" were offered, does anyone doubt that a more livable peace would soon be at hand, and that the U.S. would incur its greatest possible symbolic honor?

-

If we assume, with Baudrillard, that there is a rule of

reciprocity between conscious beings, wherein their symbolic standing

vis à vis one another depends on what they give in

exchange, and if we assume that the recognition of this rule of value

runs deeper in humans everywhere than does the recognition of the rule of

value imposed by capitalism, and if we assume that the

terrorists have appealed to this rule before the world, do we choose to

play by the rule, or to ignore it? So far the U.S. has ignored it by

refusing to answer the implicit questions: Why do they hate us? Why is

our military there? By what right do we exploit their resources,

overthrow their elected leaders, and drop bombs on their people? But no

response is still a response, symbolically speaking, and the world is

listening. What the system did in response to 9/11, or instead of

responding to it, was to re-absorb its symbolic violence back into the

never ending flow of anesthetized simulation, i.e., it has attempted "to

replace a truly formidable event, unique and unforseen, with a

pseudo-event that is as repetitive as it is familiar"

(Harper's 18). This is exactly what Baudrillard predicted

would happen in "On Nihilism," this neutralizing of the terrorist event

by the system. In "L'Esprit," he notes that:

In the terrorist attack the event eclipsed all of our interpretive models, whereas in this mindlessly military and technological war we see the opposite: the interpretive model eclipsing the event. (18)

Baudrillard would have us recognize that the attack on 9/11 succeeded in poking a hole in the U.S.'s mighty shield, thus opening a space "where seduction begins," and in provoking a murderous response. The terrorists therefore succeeded (are succeeding) in making the U.S. look bad on the symbolic battlefield, and in pushing the system further toward its limit and its implosion, a goal Baudrillard expressly favors. It seems most reasonable to conclude, however, that such violent, physical provocations serve no one, not even Baudrillard, and need not be equated with the kind of theoretical terrorism and aesthetic violence advocated by him (though one can always accuse him of being the first to blur the lines between the real and the imaginary). Given his cynicism about the system's ability to neutralize every opposition, however, Baudrillard sees such dramatic gestures (as 9/11) as naïve in their utopianism. And yet he too has his utopianism, which can be found in the silent evocation of the only decent, beautiful solution to the challenge of 9/11. Unlike naïve terrorists and secondary critics, however, Baudrillard will not speak his utopia,[8] which in this case is the possibility of forgiveness as a world-historical symbolic event. This utopian moment in Baudrillard, this idea that the U.S. might forgive its debtors, is obviously unrealistic as yet, but every challenge opens up a new space in the universe. This is where seduction begins. -

As for death, it is still un-American. We live mostly, as Ernest

Becker claimed, in denial of death, which our marketing specialists have

yet to fully package. We live in ignorance of the death and misery

caused by our military and its industry. No one knows how many lives, or

anything about the individuals killed. We see only TV spectacles. We do

not see the real, or know the real, but we are a culture fascinated by

its simulacrum. Approximately 3,000 more people joined the ranks of the

dead on 9/11 and for most of us they were only abstractions, but the

fascination we felt, the release, is something everyone is now

anticipating, every false alarm a tease. Whether we see it in

Baudrillardian or Freudian terms, this is the death drive. The most

recent Gallup poll shows 53% of Americans in favor of the U.S. invading

Iraq alone. Toward the end of Symbolic Exchange and Death,

Baudrillard states what he believes is on all of our minds:

Death itself demands to be experienced immediately, in total blindness and total ambivalence. But is it revolutionary? If political economy is the most rigorous attempt to put an end to death, it is clear that only death can put an end to political economy. (86-87)

- Forget waiting for it, let's have another spectacle; let's demand

death now! Is Baudrillard being sinister when he tempts us with our

desire for more death? Is he death's seducer? Not if we allow for his

caveat about the term "death" found in the book's second footnote: "death

ought never to be understood as the real event that affects a subject or

a body, but as a form in which the determinacy of the subject

and of value is lost" (5, n. 2). Baudrillard uses the term death to

signify "the real event" throughout Symbolic Exchange and

Death, and only sometimes uses it as a conceptual figure like

this, but if he is not talking here about real death, where some

subject and some value are certainly lost, what is he talking about?

Death, in Baudrillard's specialized sense, signifies the end of "bound

energies in stable oppositions," but since the system itself is also

capable of imposing such deaths, he clarifies that the death of the

system can only be achieved by way of its strategic reversal:

For the system is master: like God it can bind or unbind energies; what it is incapable of (and what it can no longer avoid) is reversibility. Reversibility alone therefore, rather than unbinding or drifting, is fatal to it. This is exactly what the term symbolic "exchange" means.

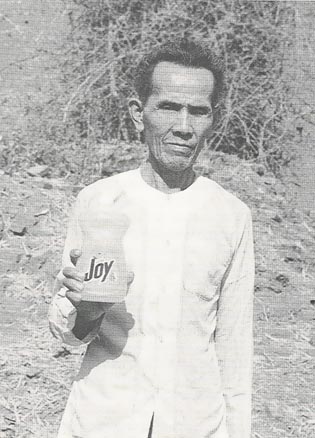

Baudrillard contends that the system cannot reverse itself, but that one might cause it to enact "death" as the form of an exchange in which its values no longer apply, in which its determinations become indeterminate. One does this by giving it a gift it cannot respond to without killing itself in this way, without undermining its own authority. This can be done effectively with words and/or pictures:

but it can also be done with jet airplanes:

Figure 1: The Selling of Joy[9]

© Thomas Antel

Used with permission of photographer

53% of our baser instincts may demand that real death, the "real event that affects a subject or a body" (whether in Baghdad or Manhattan) be experienced now, but Baudrillard does not. Baudrillard is far more nihilistic than most terrorists and warmongers. The capitalist system, he says, will sooner or later reclaim all such "freed energies." Whether or not we share his pessimism, his conception of the symbolic affords us a view of human relations that is based on recognition and reciprocity, instead of ignorance and domination, which is about what America needs right now. As for his remarks on terrorism and death, however, let us hope Baudrillard does not suffer Nietzsche's fate and wind up the misread philosopher of murderous thugs.

Figure 2

In the end it was they who did it but we who wished it. If we do not take this into account, the event loses all symbolic dimension; it becomes a purely arbitrary act. . . . (A)nd in their strategic symbolism the terrorists knew they could count on this unconfessable complicity.Terrorism is the act that restores an irreducible singularity to the heart of a generalized system of exchange.

The globe itself is resistant to globalization.

--Jean Baudrillard[1]

Department of English

University of Wisconsin, La Crosse

butterfi.brad@uwlax.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c)

2002 BY Bradley Butterfield, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THIS TEXT

MAY BE USED AND SHARED

IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR-USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW. ANY USE

OF THIS TEXT ON OTHER TERMS, IN ANY MEDIUM, REQUIRES THE CONSENT OF THE

AUTHOR AND THE PUBLISHER, THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

1. From "L'Esprit du Terrorisme" (13, 14, 18).

2. See Symbolic Exchange and Death (5, n. 2), which I discuss in the final section of this essay.

3. It is likely that Baudrillard's theory of the primitive and his whole theory of the symbolic (as gift) derive more from a history of colonial projection than from the truth about the colonized. In The Potlatch Papers: A Colonial Case History, Christopher Bracken argues that the potlatch in twentieth-century European anthropology and philosophy is the invention of a nineteenth-century Canadian law meant to outlaw it. Bracken does not mention Baudrillard, but Lyotard does along these same lines: "How is it that he does not see that the whole problematic of the gift, of symbolic exchange, such as he receives it from Mauss...belongs in its entirety to Western racism and imperialism--that it is still ethnology's good savage, slightly libidinalized, which he inherits with the concept?" (106). No longer believing in true origins, however, Baudrillard would like to be free of the distinction between the real and the imaginary savage so as to focus on the concept of symbolic exchange, a concept containing a compelling, if understated, ethic: that one must respond, and is responsible, to the other; that one's honor depends on what one gives; and that the value of the gift is not quantifiable but is symbolic. One will get nowhere trying to verify his speculations about the "real primitives," and I could not speak for indigenous people as to whether they should value his "gift" to them as a compliment or an insult. See Piper for discussion of Baudrillard's place in the new primitivist counter-culture, "the drop-out culture of the sixties redefined as both indigenous and postmodern" (177).

4. See for instance "Homer's Contest" (Portable 32-39).

5. See Stille and Alden.

6. Matthew Kelly of Brooklyn writes "I choked on the quotation marks buffeting the word 'real' . . . which, in his view, the September 11 violence was not" (86).

7. As I write, President Bush has declared a new, "preventive" unilateralism in U.S. military policy, and the Senate has authorized the President to proceed with an invasion of Iraq at his own discretion, regardless of international opinion. This current push toward global domination by force must strike all but the most authoritarian Americans as deeply ignoble. After all, it flies in the face of our TV and Hollywood upbringing, which teaches us that it's only bad guys who want to rule the world and that nobody should end up as "lord of the rings." Indeed, the contradiction between image and reality is becoming so apparent that, in keeping with the Orwellian nature of the Bush administration, we might almost expect revisionist remakes to start replacing the standard Hollywood movies. We'll find that Austin Powers and Dr. Evil have somehow changed roles, and that we're cheering for good guys who rule the world with an iron hand while egalitarian villains plot against them.

8. In The Illusion of the End, Baudrillard cites Adorno to this effect: "Every ecstasy ultimately prefers to take the path of renunciation rather than sin against its own concept by realizing itself" (104).

9. There's a powerful narrative implied in this photo; an annoyed resident of the so-called "third world" holds a box of Joy for the camera, and suddenly we don't feel so happy about Joy. When we are made conscious of the implicit, metaphysical insult of a class-based global village, we are made aware of the symbolic standing between the first world and the third. The anti-commercial is a symbolic challenge to the real commercial, posing one image against another, demanding a response. Baudrillardian symbolic exchange is based on this principle of reversal and seduction, and so has much in common with Guy Debord's and the Situationists' concept of "detournement" and with what Kalle Lasn and Adbusters call "culture jamming" (see Lasn 103-109).

Works Cited

Alden, Dianne. "History is the Root Cause of Everything." NewsMax.com 11 Oct. 2002. 29 Aug. 2002. <http://www.tysknews.com/Depts/terrorism/root_cause.htm>.

Andreas, Joel. Addicted to War: Why the U.S. Can't Kick Militarism. Oakland: AK, 2002.

Baudrillard, Jean. Baudrillard Live: Selected Interviews. Ed. Mike Gane. New York: Routledge, 1993.

---. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. Trans. Charles Levin. St. Louis, MO: Telos, 1981.

---. The Illusion of the End. Trans. Chris Turner. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1994.

---. "L'Esprit du Terrorisme." Trans. Donovan Hohn. Harper's Magazine (February 2002): 13-18.

---. Simulacra and Simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1994.

---. Symbolic Exchange and Death. Trans. Iain Hamilton Grant. London: Sage, 1993.

Bracken, Christopher. The Potlatch Papers: A Colonial Case History. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1997.

Butler, Rex. Jean Baudrillard: The Defense of the Real. London: Sage, 1999.

Kellner, Douglas. Jean Baudrillard: From Marxism to Postmodernism and Beyond. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1989.

Kelly, Mathew; Schlesinger, Edward B.; Wersan, Sarah A. "Letters to the Editor." Harper's Magazine (May 2002): 4.

Lasn, Kalle. Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America™. New York: Eagle Brook, 1999.

Lyotard, Jean-François. Libidinal Economy. Trans. Iain Hamilton Grant. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1993.

Mauss, Marcel. The Gift: the Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Trans. W.D. Halls. New York: Norton, 1990.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Genealogy of Morals. Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1967.

---. The Portable Nietzsche. Ed. and Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Penguin, 1954.

Piper, Karen. Cartographic Fictions: Maps, Race, and Identity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2002.

Stille, Alexander. "The Many Meanings of 9/11." Council on Foreign Relations. (2001). 29 Aug. 2002. <http://www.cfr.org/Public/publications/xStille.html>.