Danger Mouse's Grey Album, Mash-Ups, and the Age of Composition

Philip A. GundersonSan Diego Miramar College

pgunders73@hotmail.com

© 2004 Philip A. Gunderson.

All rights reserved.

Review of:

Danger Mouse (Brian Burton), The Grey Album, Bootleg Recording

- Depending on one's perspective, Danger Mouse's (Brian Burton's) Grey Album

represents a highpoint or a nadir in the state of the recording arts in 2004. From the

perspective of music fans and critics, Burton's creation--a daring "mash-up" of Jay-Z's

The Black Album and the Beatles' eponymous 1969 work (popularly known as The

White Album)--shows that, despite the continued corporatization of music, the DIY ethos

of 1970s punk remains alive and well, manifesting in sampling and low-budget, "bedroom studio"

production values. From the perspective of the recording industry, Danger Mouse's album

represents the illegal plundering of some of the most valuable property in the history of

pop music (the Beatles' sound recordings), the sacrilegious re-mixing of said recordings with

a capella tracks of an African American rapper, and the electronic distribution of the

entire album to hundreds of thousands of listeners who appear vexingly oblivious to current

copyright law. That there would be a schism between the interests of consumers and the

recording industry is hardly surprising; tension and antagonism characterize virtually all

forms of exchange in capitalist economies. What is perhaps of note is that these

tensions have escalated to the point of the abandonment of the exchange relationship

itself. Music fans, fed up with the high prices (and outright price-fixing) of commercially

available music,

have opted to share music files via peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and record labels

are attempting in response to coerce music

fans back into the exchange relationship. The

Grey Album and the mash-up form in general are symptomatic of an historical moment in

which the forces of music production (production technology, artistic invention, and web-based

networks of music distribution) have greatly exceeded the present relations of production expressed

by artist/label contracts, music property rights, and traditional producer/consumer dichotomies.

The Forces of Production

- Mash-up artists such as Danger Mouse have shown how the recording industry has been rendered superfluous by advances in music production technology. Artists once had to play the record companies' games in order to gain access to precious time in a recording studio; today, a "bedroom producer" can create a professional sounding album with a personal computer alone. (Brian Burton is known to have used Sony's Acid Pro.) Indeed, insofar as they want to survive, real studios have had to integrate "virtual" studios into their setup. Many commercial production houses incorporate software into their own environments so that their customers will be able to transfer their work between PC and studio, where it can be further processed. One is tempted to speculate that late capitalist society is on the cusp of the "composition" stage of musical development, as described in Jacques Attali's Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Attali argues that music's social function has passed through three distinct stages: sacrifice (the assertion of control over violence), representation (the creation of socially meaningful works), and repetition (the reproduction and dissemination of music apart from social context). The fourth and final stage, "composition," is essentially utopian: the production of music by and for its own consumers. The traditional opposition of the active producer and passive consumer disappears in the age of composition. Although music production software remains far from universally accessible (most of the planet's population does not have easy access to a telephone, let alone a computer), the increasingly wide availability of powerful computers in advanced capitalist countries suggests a gradual democratization of technology that does foster utopian impulses.

- This change in the material conditions of production has significant aesthetic consequences. Noodling about in a studio was not an option except for the wealthiest bands (such as the Beatles), and, as a result, most artists treated the recording environment more as a mimetic recording instrument, as a means of capturing a live musical performance or at least creating the semblance of a live musical performance, than as a musical instrument in its own right. Liberated from the traditional recording studio (and its institutional supports), the contemporary musician is free to experiment at his or her leisure with ideas and recording techniques that would have been considered too unconventional and even risky in the past. The Grey Album is a perfect example of the kind of artistic experimentation that can result: combining a capella tracks of a famous rapper with pop classics by a band whose record label has never licensed samples of their music for use by other artists is something that would not have happened in a professional recording studio under any circumstances. When artists cease to be constrained by the demands of the market (which include both studio executives' demands for a hit single and the restrictive demands of today's consumer, who has been conditioned to dislike any music that makes its own demands on the listener), they may pursue other logics internal to their work. In Attali's age of composition, the idea of aesthetic autonomy appears on the horizon.

- The audio cut-and-paste, pastiche technique of The Grey Album might seem an unlikely candidate for such a modernist notion as "aesthetic autonomy," but in a culture saturated by sham originality (and the actualization of art in the commodity form) the only viable gesture towards autonomy would have to be the representation of cultural contradiction itself. The Grey Album, with its violation of copyright laws, realizes the extent to which said laws have been put to purposes in contradiction with their original intent. That is, the original function of copyright was to encourage social advance by giving creators a financial stake in their work and by insisting that intellectual property become, after a reasonable period of time, public property. Walt Disney has long since been dead, but his intellectual property, Mickey Mouse and friends, has passed on to another legal "person," i.e., Disney, Inc., who/that has successfully fought to extend copyright protections for reasons of "personal" profit. Public benefit has been effectively factored out of current copyright law. Monopoly capital has turned a legal spur to innovation and creativity into a tool for artistic repression.

- Although its title might suggest a homogenizing synthesis of opposites (the admixture of black and white to form grey--a dialectical fog in which all musicians are grey, as it were), part of The Grey Album's vibrancy comes from the way it highlights the culture industry's specious opposition of white 1960s Brit-pop and twenty-first century black American hip-hop. In the contemporary climate of administrated music, in which radio bandwidth has been exploded into a stelliferous system of synchronic generic differences (classic rock, alternative rock, "urban," classical, country, etc.) and which interpellates a corresponding "type" of consumer, The Grey Album's juxtaposition of the Beatles and Jay-Z takes on the character of a musical contradiction in terms. That The Grey Album can be regarded as such a novelty (even as a musical miracle) belies the extent to which the enforcement of categorical differences in administrated music discourages critical reflection on--and simple awareness of--the history of popular music and its innate syncretism, its vital habit of "borrowing" across the lines of race, class, gender, and national identity. Danger Mouse's Grey Album forcibly reminds its listeners of the diachronic becoming of popular music. By mashing-up Jay-Z and the Beatles, Danger Mouse, himself a black Briton, highlights the fact that African American hip hop is in many ways a direct descendent of sixties-era British rock--and that British rock is largely a descendent of early twentieth century African American blues, which in turn owes something to Christian spirituals sung on plantations. Introspective listeners will recognize the album's dialogic structure, and some may even be moved to ask questions about the asymmetrical relations of power that saturate the evolution of popular music.

- The Grey Album is not, however, only a history lesson--it is itself an act of resistance. It is, to employ Deleuzian terminology, a kind of "war machine" at work within and against the edifice of mass music. It is rhizomatic in the way it forms transversal relations between genres that have been arborescently structured by the recording industry. The bastard births of the mash-up form--the offspring of forbidden sonic cross-pollinations--tangle the genealogical lines of musical descent, thus leading to the common disparagement of sampling as a form of musical incest. Indeed, the very metaphor of the "mash-up" suggests a process of destructuring, an introduction of confusion, a production of indistinction in which this cannot be told from that. One could look askance at mash-ups, viewing them as puerile, disrespectful mucking about with other people's property, but one could also celebrate that very puerility insofar as it is anti-oedipal--insofar as it short-circuits the culture industry's normally enforced boundaries between disparate genres of music. The sense of humor immanent to a good mash-up (such as Soulwax's "Smells Like Booty," a fusion of Nirvana and Destiny's Child), seems particularly amenable to explanation in terms of Freud's theory of humor as a mechanism that relies on the sudden lifting of the repression on psychic energy. Our smiles and laughter signify our liberation from an excessively restrictive horizon of musical expectations. Psychic energy that had been channeled into rote pathways suddenly streams in unpredictable directions across the surface of culture. The mash-up artist is not at all the sad militant bemoaned by Foucault in his preface to Anti-Oedipus but rather an ethicist in the most Spinozist sense, perpetually in battle with the sad passions that prevent our bodies from realizing their affective powers.

- Another undeniably "puerile" pleasure in the mash-up form (in addition to its

proclivity for crossing genres) is its willingness to dance on the graves of pop music's

forbears. Danger Mouse's gesture with The Grey Album is in some ways analogous to

Duchamp's gesture with L.H.O.O.Q. Just as Duchamp scandalized bourgeois

fetishists of Renaissance art by painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa (and implying

with his title that the original model had a "hot ass"), Danger Mouse zeroes in on the musical

institution the Beatles have become and appropriates their sounds into a new, critical

context. If art is to move forward, both artists seem to be implying, it can only do so when

repressive pieties are broken down and humor injected into the mix.

Distribution Networks

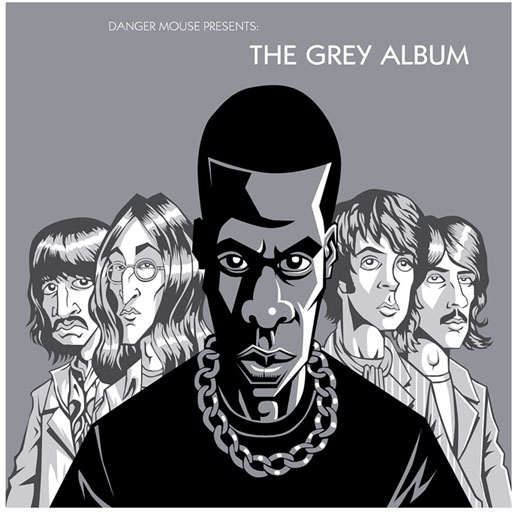

- Danger Mouse initially produced a few thousand copies of The Grey Album for friends and distributed copies to independent music retailers. The modest scale of production suggests that the artist's motivations were far from mercenary. Danger Mouse stood to gain little profit, if any, from his efforts. The Grey Album CD featured Jay-Z in the foreground with his "backing band" arrayed behind him:

- As soon as it became aware of the compact disc, EMI issued cease-and-desist papers to Brian Burton--he was not to produce additional copies of the album and all distributors were to destroy any copies remaining in their possession. EMI's ham-fisted attempts at repression provoked a grass-roots Internet campaign that effectively demonstrated the ability of peer-to-peer file sharing technology to supplant the distribution of data encoded physical media (CDs, tapes, records, etc). On 26 February, "Grey Tuesday," nearly two hundred websites defied EMI and posted the entirety of The Grey Album in MP3 file format for easy, free download to any computer connected to the Internet. Well publicized by word of mouth, popular media, and the Web, Grey Tuesday was an unqualified (and unauthorized) success. Disobedient consumers, who had not been given the option of purchasing the album through "legitimate" commercial channels, downloaded in excess of one million Grey Album tracks. Had it been available for purchase at a brick-and-mortar store, such numbers would have put the album firmly in Billboard's Top Ten.

- Grey Tuesday, in its scope and success, can be taken as something akin to the dawning of a consumer class consciousness--members of the Internet community had the collective knowledge and means to put a popular work of art into circulation without the support or permission of the recording industry. One could say that consumers have taken over the distribution of musical goods and services to the detriment of those who have heretofore controlled the means of musical production. The near-instantaneous, viral replication of information on a global network renders moot the legal formalities of trademark and copyright. The traditional radio station, with its fixed formats and mind-numbingly repetitive playlists, has been effectively displaced by technologies that allow music fans to specify what they want to hear and when they want to hear it. Radio and online broadcasting remain useful avenues for discovering new artists, but control over the music is no longer contingent upon the exchange of cash. In the age of digital communism, a song's exchange value evaporates as soon as that song hits the network.

- And it is a matter of communism. Although file-sharing has been besmirched with the label of "piracy" by the institutional purveyors of pop, the phenomenon actually suggests a heartening generosity on the part of consumers. As much as consumers are taught to fetishize status symbols (commodities that identify one as a member of the "haves" as opposed to the "have-nots"), file-swapping suggests that they are inclined to share whenever they stand to lose nothing. The record labels will, or course, respond that consumers will collectively lose when the industry can no longer afford to develop and market new talent. To this objection one may answer that the atrophy of one arm of the culture industry hardly amounts to public hardship. As consumers become accustomed to looking for good music online, they will need to rely on commercial tastemakers less. They may, indeed, find the industry's "pushing" of mass entertainment increasingly odious. To approach the same issue from a slightly different angle, file sharing threatens to dispel musical ignorance and the industry that profits there from. Music fans trained to think that the major labels are the only sources of music worth listening to discover in the Internet a repository of innovative, challenging music--music, indeed, whose only evident failing has been that it is perhaps too innovative and too challenging for benumbed Clear Channel Communications listeners.

- If Attali is correct that music acts as a harbinger of social change, then

artists like Danger Mouse may be taken as cultural prophets. They preach a new economics: the

communism of simulacra, the unrestricted sharing of digital copies without originals. This new

economics deterritorializes the culture industry; it threatens all industries that have

traditionally profited as the producers and gatekeepers of information. Whereas communist

regimes in the previous century could not withstand the onslaught of cheap commodities from

capitalist countries, today we find capitalist countries increasingly vulnerable to the

world's data commies--Danger Mouse, Linus Torvald, Shawn Fanning, and all those

who are dedicated to the free flow of information.

English Department

San Diego Miramar College

pgunders73@hotmail.com

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2004 BY Philip A. Gunderson. READERS MAY USE PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTIONS MAY USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE. FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO PROJECT MUSE, THE ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Works Cited

Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1985.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. New York: Viking, 1977.

Freud, Sigmund. Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. New York: Norton, 1963.

|

|

| Figure 1: The Grey Album Design © 2004 kaos <worldofkaos.com> |