- "For Skies grow thick with aviating Swine, / Ere men pass up the chance to draw a Line.... Sharing a Fate, directed by the Stars, / To mark the Earth with geometrick Scars." ¶¶ C. Mason & J. Dixon have come to America to draw a Line fixing "the Boundaries between the American Provinces of Pennsylvania and Maryland” (182). Both conceptually and contextually, this line is suspended into a variety of parameters, and it designates, for the various voices that make up the multiplex harmonics of the narrative, a number of diverging frameworks. At one point, for instance, the feng shui master Zhang accuses Mason & Dixon--"you two crazy?" (542)--of the straightness of the Visto which he sees as a "conduit for Evil" (701): "Ev'rywhere else on earth, Boundaries follow Nature,--coast-lines, ridge-tops, river-banks,--so honoring the Dragon or Shan within, from which Land-Scape ever takes its form. To mark a right Line upon the Earth is to inflict upon the Dragon's very Flesh, a sword-slash, a long, perfect scar, impossible for any who live out here the year 'round to see as other than hateful Assault" (542). In this description, the line is seen as a traumatic wounding of the body of America; a "Telluric Injur[y]" (544).¶ It is in particular the straightness of the tracing and its disregard of natural contours that define the line as an incision into the body of the earth with the scalpel of human rationality. The difference between "enlightened rationality" (order) and "the earth" (chaos) is negotiated over "the distinction between Blade and Body,--the aggressive exactitude of the one [and] the helpless indeterminacy of the other" (545). As such, the line is a variant of earlier historical lines, because already the Romans "were preoccupied with conveying Force, be it hydraulic, or military, or architectural,--along straight Lines" (219). In fact, "Right Lines beyond a certain Magnitude become of less use or instruction to those who must dwell among them, than intelligible, by their immense regularity, to more distant Onlookers, as giving a clear sign of Human Presence upon the Planet" (219). Yet the visto is also a specifically American line on "the Boundary between the Settl'd and the Unpossess'd" (282) that will "in futurity" become the dividing line between freedom and slavery. And, in a flash-forward, it is the prototype of the 20th century Strip: "the Visto soon is lin'd with Inns [read: motels] and Shops, Stables [read: parking lots], Games of Skill [read: video-arcades], Theatrickals [read: movie theaters], Pleasure Gardens [read: sex shops]... a Promenade,--nay, Mall,--eighty Miles long" (701). [1]

-

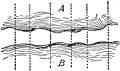

In all of its aspects, the visto figures the "line of progress," rational

ideology and teleology, all of which cut across "scatterbrained nature"

and an originally multiplex history, which has a much more disorderly

structure, because it is "not a Chain of single Links... [but]--rather, a

great disorderly Tangle of Lines, long and short, weak and strong,

vanishing into the Mnemonick

Deep, with only their Destination in common" (349).¶ As one example

of "the inscription upon the Earth of... enormously long straight Lines"

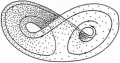

(546), the line is also a variation of an originary line between the

transcendental,

heavenly realm

and that of the earth. (This juxtaposition is taken up by

the character constellation with Mason [the astronomer] representing the

spirit and the sky and Dixon [the surveyor] representing the body and the

earth.) This originary line is the primal scene of the many divisions that

would come to define (not only) America in the context of the Biblical

story of genesis; a story used by Jacques Lacan in his commentary to

de Saussure's

theory of language to designate the separation of the signifier and the

signified. As Lacan states about de Saussure's famous diagram: "an image

resembling the wavy lines of the upper and the lower Waters in miniatures

from manuscripts of Genesis; a double flux marked by fine streaks

of rain" (Écrits. New York: Norton, 1977. 154). In

Mason & Dixon, Mr. Edgewise takes up this division,

which makes of the

line also a "stroke of the letter" and thus a figure of the signifier:

"the second Day of Creation, when 'G-d made the Firmament, and divided

the Waters which were under the Firmament, from the Waters which were above

the Firmament,'--thus the first Boundary Line. All else after that, in

all History, is but [here the American and not the German mania for] Sub-Division"

(361). [2]

and that of the earth. (This juxtaposition is taken up by

the character constellation with Mason [the astronomer] representing the

spirit and the sky and Dixon [the surveyor] representing the body and the

earth.) This originary line is the primal scene of the many divisions that

would come to define (not only) America in the context of the Biblical

story of genesis; a story used by Jacques Lacan in his commentary to

de Saussure's

theory of language to designate the separation of the signifier and the

signified. As Lacan states about de Saussure's famous diagram: "an image

resembling the wavy lines of the upper and the lower Waters in miniatures

from manuscripts of Genesis; a double flux marked by fine streaks

of rain" (Écrits. New York: Norton, 1977. 154). In

Mason & Dixon, Mr. Edgewise takes up this division,

which makes of the

line also a "stroke of the letter" and thus a figure of the signifier:

"the second Day of Creation, when 'G-d made the Firmament, and divided

the Waters which were under the Firmament, from the Waters which were above

the Firmament,'--thus the first Boundary Line. All else after that, in

all History, is but [here the American and not the German mania for] Sub-Division"

(361). [2]

- In this light, the visto is the emblem of every cultural demarcation and ordering. As one can read in Walt Whitman's "Democratic Vistas" (in: Complete Poetry and Selected Prose. Ed. J. E. Miller. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959. 455-501), "of all dangers to a nation... there can be no greater one than having certain portions of the people set off from the rest by a line drawn," and the parallel in Mason & Dixon: "Nothing will produce Bad History more directly nor brutally, than drawing a Line, in particular a Right Line, the very Shape of Contempt, through the midst of a People,--to create thus a Distinction betwixt 'em,--'tis the first stroke.--All else will follow as if predestin'd, unto War and Devastation" [615]: [3]

- in the context of the line as a linguistic line--in which the world becomes, as in so many other of Pynchon's works, a text that has to be interpreted: "This 'New World' was ever a secret Body of Knowledge,--meant to be studied with the same dedication as the Hebrew Kabbala.... Forms of the Land, the flow of water... all are Text [the "Real Text" of Gravity's Rainbow],--to be attended to, manipulated, read, remember'd... a Tellurian Scripture.... A smaller Pantograph copy down here, of Occurrences in the Higher World" (487)--the most important cultural message of the line is control, because it changes the meaning of the telluric sentence from the subjunctive and the conditional (and thus from chaotic complexity) to the declarative and the factual (and thus to ordered simplicity): [4]

- with the frontier "the Membrane that divides their [the Native American's] Subjunctive World from our number'd and dreamless Indicative," (677) [5]

- while narratologically (in relation to the conceit of the world as a text), the line is also related to the difference between fact and fiction, "for as long as its [the country's] Distance from the Post Mark'd West remains unmeasur'd, nor is yet recorded as Fact, may it remain, a-shimmer, among the few final Pages of its Life as Fiction" (650). Ultimately, the line changes language games (fictions) to protocols and to controls (facts). In this context, the "fictional" America had served as "a very Rubbish-Tip for subjunctive Hopes, for all that may yet be true" (345): [6]

- The fictional, multiplex America had been a wilderness, "safe till the next Territory to the West be seen and recorded, measur'd and tied in... changing all from subjunctive to declarative, reducing Possibilities to Simplicities that serve the ends of Governments,--winning away from the realm of the Sacred, its Borderlands one by one, and assuming them unto the bare mortal World that is our home, and our Despair" (345, emphasis added). The world that Pynchon had described in Vineland as "the spilled, the broken world" (Boston: Little Brown, 1990. 267). The line of control, however, is embedded in the unaccountable changes brought about by history, its tangled complexity (which was already too complicated to compute for Brigadier Pudding in Gravity's Rainbow [New York: Viking, 1973], and in which every situation, as Father Fairing had found out in V. [Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1963. 470], is already "An 'N-Dimensional Mishmash'") and thus, as one character notes, to draw it is "an exercise in futility! I can't believe you Cuffins! In a few seasons hence, all your Work must be left to grow over, never to be redrawn, for in the world that is to come, all boundaries shall be eras'd" (406). [7]

- "That failure of perfect Return, that haunts all for whom Time elapses. In the runs of Lives, in Company as alone, what fails to return, is ever a source of Sorrow" (630).¶¶ A trauma is the effect of an incisive wound:ing, and the tragedy of trauma lies in the fact that this violent event is, in its sheer terror, an irretrievably lost moment that can only be treated belatedly, that is, after the event. Within this traumatic logic, the traumatic moment (the traumacore) comes to function as an "attractor," a lost scene that will be psycho-pathologically repeated again and again, in ever new variations and in ever new scenarios, without the hope of ever either completely retrieving it or canceling it out. Without the hope of escaping the scarification that any attempt at suturing entails. In terms of the line, this traumatic moment designates the destruction of the "single realm... that undifferentiated Condition before Light and Dark,--Earth and Sky, Man and Woman,--... that Holy Silence which the Word broke, and the Multiplexity of matter has ever since kept hidden, before all but a few resolute Explorers" (523, emphasis added). [8]

- If the single realm was that of a time "before" (too early), everything about the trauma is belated, missed and forever too late. Symptomatically, Cherrycoke's story is irredeemably belated. He is the prototype of memory itself, a highly unreliable narrator, or, in the back-projection of the term into the 18th century, an "untrustworthy Remembrancer" (8). In fact, like the real, multiplex historical moment, he is only virtually there, as a yet to-be-written narrative, and thus as the events' unconscious: "the Revd... was there in but a representational sense, ghostly as an imperfect narrative to be told in futurity" (195).¶ In this light, Mason & Dixon charts out the loss even while describing the moment of traumatic wounding, with the description of Mason's and Dixon's journey becoming a slow-motion representation of the traumatic incision and of its narrative suturing. The timelessness of this incision is taken up in the repetitive movements of the book, which go from inn to inn, as well as in the convolution of the stories that twine around the (not only narrative) line.¶ If the drawing of the line equals the relentless traumatization of a timeless and silent nature into human (especially Western) history and representation, it is countered by a specific moment in the story that describes a once more timeless moment within human time. Pynchon very carefully relates this lost time to the topology of the line, because he describes it as a "slowly rotating Loop, or if you like, Vortex" tangent to the chronological and entropic time-line, "excluded from it, and repeating itself,--without end" (555). This Loop results from the shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar during the "Schizochronick year" 1752 (192, emphasis added), and it concerns the "Eleven Missing Days [June 2nd to June 14th] of the Calendar Reform of '52" (554). As Cherrycoke tells his listeners, already linking time to space and to trauma: "Those of us born before that fateful September... make up a generation in all British History uniquely insulted, each Life carrying a chronologick Wound, from the same Parliamentary stroke (555, emphasis added). At one point, Mason finds himself in the vortex of this temporal maelstrom; an event described as a traumatic "Tear thro' the fabric of Life" (555). Symptomatically, his time travel is related to a "lapse of consciousness" (566). The envortic'd time, which Mason already links to lost space by describing it as "Tempus Incognitus" (556), is a "mirror-time" outside of the realm of (the age of) reason, defined by the fear of and the fascination with the relentless return of everything irrational and unreasonable: "'Twas as if this Metropolis of British Reason had been abandon'd to the Occupancy of all that Reason would deny. Malevolent shapes flowing in the Streets.... A Carnival of Fear. Shall I admit it ? I thrill'd. I felt that if I ran fast enough, I could gain altitude, and fly" (559-60). In Mr. Bodley's library, he finds in the shelves "unallowed books" (among them, of course, Eco's fictional book "Aristotle on Comedy" [559]) and uncanny "Presences" (559) wishing to communicate. Before he can enter deeper into this realm, however, Mason is flung out of the vortex and pulled back into real time, drawn partly by the "Presences" who turn out to have been: "Wraiths of those who had mov'd ahead instantly to the Fourteenth, haunting me not from the past but from the Future" (560). Sooner than he wished to be, he is back on the line. [9]

-

"Is not our own interior white on the chart?... you may perhaps find some

'Symmes' Hole' by which to get inside at last" (Henry David Thoreau,

Walden).¶¶

Dr. Cyrus Read Teed, also known as Koresh, was convinced that humans live

on the inside of a concave earth. In an attempt to prove his theory

scientifically, he built, in 1897, with the help of Prof. Morrow, a measuring

device he called the "Rectilineator." The Rectilineator is based on the

model of the perfectly straight line. The argument is as simple as it is

ingenious. If the earth is concave, a perfectly straight line, starting

a small distance from the earth at a perfectly level ground will, after

some time, have to touch the ground: "On January 2, 1897, the Koreshan

Geodetic Survey... arrived at the long, level beach of Naples, Florida...

they erected the Rectilineator and began their measurements.... It took

the Koreshan Geodetic Survey five months to move the Rectilineator, section

by section, the distance of four miles. But on May 5, 1897, the line struck

the water and a great cheer of thanksgiving arose from Morrow and his men.

Their work was not in vain; Koresh was right. The earth was concave"

(Krafton-Minkel, Walter. Subterranean Worlds: 100,000 Years of

Dragons, Dwarfs, the Dead,

Lost Races & UFOs from Inside the Earth. Port Townsend,

WA: Loompanics Unlimited, 1989. 100).¶ Equivalent to Mason's lost

time,

there are a number of lost spaces and free "Zones" in Mason &

Dixon,

such as the Hollow Earth to which Dixon, the telluric part of the duo,

travels. In this concave world everything one sees is land and "to journey

anywhere... is ever to ascend. With its Corollary,--Outside, here upon

the Convexity,--to go anywhere is ever to descend" (740). The inhabitants

of this world are "Gnomes, Elves, smaller folk, who live underground" (740)

whose existence is endangered because "Once... the size and weight and

shape of the Earth are calculated inescapably at last [what Baudrillard

would call a state

of simulation, which coincides here with Adorno's image

of the completion of the project of the Enlightenment], all this will vanish.

We will have to seek another Space" (741). Maybe some of them will be able

to adjust to the broken, convex world, which is so "exposed to the Outer

Darkness.... And wherever you may stand, given the Convexity, each of you

is slightly pointed away from everybody else.... Here in the Earth

Concave, everyone is pointed at everyone else,--ev'rybody's axes

converge,--forcd'd at least thus to acknowledge one another,--an entirely

different set of rules for how to behave [a concave ethics]" (741).¶

Both journeys promise escapes, one from chronological time and the other

from the space of the "broken" world. As true utopias, both countries lie

in im:possible times and spaces; temporal and spatial "nowheres." They

are phantasms, belated, dreamed-up constructs that make up for a more originary

loss. Pynchon, however, has always been concerned with excluded middles,

and ultimately, the topology of Mason & Dixon's poetics calls for a

more basic intermingling of extremes (and these include the extremes of

body and soul, language and silence, chaos and control, feng shui and

rationalism, freedom and slavery, life and death, as well as inside and

outside). In

this context, the "strange narrative loop" (the only truly im:possible

narratological embedding) of Eliza's tale is crucial, as a textual figure

of a moment when "Lies and Truth" (530) converge.¶ Such interminglings

finds their figure in the topology of the Möbius-strip, which can

come to stand for Pynchon's poetics in their celebration of ambiguities

and their refusal to ultimately "take sides." It might, therefore, be more

than a throwaway reference when Pynchon evokes the "invention

avant-la-lettre" of the Möbius-strip in the image of a

möbial smoke ring. "The

[Stogie's] Secret's in the Twist they put into the handful of Leaves whilst

they're squeezin' it into Shape.... Gives the Smoke a Spin.... He sets

his Lips as for a conventional, or Toroidal, Smoke-Ring, but out instead

comes a Ring like a Length of Ribbon clos'd in a Circle, with a single

Twist in it, possessing thereby but one Side and one Edge" (345).¶

If the lost spaces and times promised an (albeit phantasmatic) escape from

the line, there are also (probably less phantasmatic?) promises of an escape

(of "lines of flight") that are inherent in matter and its organization

as such. The materiality of the world and its complexity (the multiplexity

of matter, which is mirrored in the multiplicity of the voices and stories

in Mason & Dixon) is the link to the many references to chaos

theory and to the theory of complexity in the novel, a scientific matrix

that has taken over the more negative visions of entropic decay in Pynchon's

work, in a shift from an "entropics" to a "chaotics." [10]

would call a state

of simulation, which coincides here with Adorno's image

of the completion of the project of the Enlightenment], all this will vanish.

We will have to seek another Space" (741). Maybe some of them will be able

to adjust to the broken, convex world, which is so "exposed to the Outer

Darkness.... And wherever you may stand, given the Convexity, each of you

is slightly pointed away from everybody else.... Here in the Earth

Concave, everyone is pointed at everyone else,--ev'rybody's axes

converge,--forcd'd at least thus to acknowledge one another,--an entirely

different set of rules for how to behave [a concave ethics]" (741).¶

Both journeys promise escapes, one from chronological time and the other

from the space of the "broken" world. As true utopias, both countries lie

in im:possible times and spaces; temporal and spatial "nowheres." They

are phantasms, belated, dreamed-up constructs that make up for a more originary

loss. Pynchon, however, has always been concerned with excluded middles,

and ultimately, the topology of Mason & Dixon's poetics calls for a

more basic intermingling of extremes (and these include the extremes of

body and soul, language and silence, chaos and control, feng shui and

rationalism, freedom and slavery, life and death, as well as inside and

outside). In

this context, the "strange narrative loop" (the only truly im:possible

narratological embedding) of Eliza's tale is crucial, as a textual figure

of a moment when "Lies and Truth" (530) converge.¶ Such interminglings

finds their figure in the topology of the Möbius-strip, which can

come to stand for Pynchon's poetics in their celebration of ambiguities

and their refusal to ultimately "take sides." It might, therefore, be more

than a throwaway reference when Pynchon evokes the "invention

avant-la-lettre" of the Möbius-strip in the image of a

möbial smoke ring. "The

[Stogie's] Secret's in the Twist they put into the handful of Leaves whilst

they're squeezin' it into Shape.... Gives the Smoke a Spin.... He sets

his Lips as for a conventional, or Toroidal, Smoke-Ring, but out instead

comes a Ring like a Length of Ribbon clos'd in a Circle, with a single

Twist in it, possessing thereby but one Side and one Edge" (345).¶

If the lost spaces and times promised an (albeit phantasmatic) escape from

the line, there are also (probably less phantasmatic?) promises of an escape

(of "lines of flight") that are inherent in matter and its organization

as such. The materiality of the world and its complexity (the multiplexity

of matter, which is mirrored in the multiplicity of the voices and stories

in Mason & Dixon) is the link to the many references to chaos

theory and to the theory of complexity in the novel, a scientific matrix

that has taken over the more negative visions of entropic decay in Pynchon's

work, in a shift from an "entropics" to a "chaotics." [10]

-

The möbial topology of "strange attractors"--evoked, for instance,

in the expression "strangely attractive" (591)--can figure the "processual

topology" of Pynchon's poetics. In fact, Dan O'Hara has related, in a very

fitting image, the form of the ampersand in the novel's title to that of

a strange attractor, and one might indeed map the structure of the novel

onto the figure of a strange attractor, with Mason and Dixon representing

one of its leaves respectively.¶ In the novel, the American continent

is described as a multiplex field (a Deleuzian "body without organs") that

had promised to be too difficult to completely territorialize. As the surveyor

Shelby states, "There is a love of complexity, here in America... no previous

Lines, no fences, no streets to constrain polygony however extravagant...

all Sides zigging and zagging, going ahead and doubling back, making

Loops inside Loops,--in America, 'twas ever, Poh! to Simple Quadrilaterals"

(586). Ultimately, the fight over America is the one between complexity

(movements of deterritorialization, "lines of flight," and molecular

arrangements)

and control (movements of territorialization, "lines of segmentarity," and

The möbial topology of "strange attractors"--evoked, for instance,

in the expression "strangely attractive" (591)--can figure the "processual

topology" of Pynchon's poetics. In fact, Dan O'Hara has related, in a very

fitting image, the form of the ampersand in the novel's title to that of

a strange attractor, and one might indeed map the structure of the novel

onto the figure of a strange attractor, with Mason and Dixon representing

one of its leaves respectively.¶ In the novel, the American continent

is described as a multiplex field (a Deleuzian "body without organs") that

had promised to be too difficult to completely territorialize. As the surveyor

Shelby states, "There is a love of complexity, here in America... no previous

Lines, no fences, no streets to constrain polygony however extravagant...

all Sides zigging and zagging, going ahead and doubling back, making

Loops inside Loops,--in America, 'twas ever, Poh! to Simple Quadrilaterals"

(586). Ultimately, the fight over America is the one between complexity

(movements of deterritorialization, "lines of flight," and molecular

arrangements)

and control (movements of territorialization, "lines of segmentarity," and

molar machines): the

fight between "the Age of Metamorphosis, with any

turn of Fortune a possibility" (53), and the Company (a.k.a. "the Firm"

and "They" from Gravity's Rainbow), "who desire total Control

over ev'ry moment of ev'ry Life here" (154). [11]

molar machines): the

fight between "the Age of Metamorphosis, with any

turn of Fortune a possibility" (53), and the Company (a.k.a. "the Firm"

and "They" from Gravity's Rainbow), "who desire total Control

over ev'ry moment of ev'ry Life here" (154). [11]

- Chaos theory is itself born out of the foam of the theory of fluids. Fittingly, it is particularly the movement of fluids that Pynchon uses as a juxtaposition to the straightness of the line; with straightening-up invariably going hand in hand with a relentless operationalization and simulation.¶ The theory of flows is taken up in Pynchon's discussion of mathematical Fluxions, the 18th century equivalent to differential calculus and infinitesimals, and tools in the study of change (which is of course a favorite Pynchonesque topic, especially from Gravity's Rainbow). In the novel, fluxions (a term taken from Newtonian infinitesimal calculus, where it designates an infinitesimally small, digital difference) as opposed to fluctuations (which designate analogue movement) are "pornographies of flow" rather than of flight, agents through which it is possible to translate real movement into its false representation. The narration relates fluxions to the--also in the real-life version--highly ambiguous figure of Emerson, who comments (in a flash-forward to Bergson) about this translation, "Flow is his passion. He stands waist-deep in the Tees, fishing, contemplating its currents.... Emerson has no patience with analysis. He loves Vortices, may stare at 'em for hours, if he's the time, so far as they remain in the River,--yet, once upon Paper, he hates them, hates the misuses,--and therefore hates Euler, for example, at least as much as he reveres Newton. The first book he publish'd was upon Fluxions" (220). Emerson--who at other times is flying with his students over the English landscape--is a rationalist, who separates clearly between the realms of life and of science. In this context, his hatred of Euler might not only be related to his mathematical beliefs and studies of fluid dynamics and topology, but also to the latter's belief, itself taken over from Halley, in the existence of a Hollow Earth.¶ If vortices and the chaotic theory of flows are acceptable in the realm of life, in the realm of science, everything must be reduced to Newtonian reason. In fact, Emerson "has devis'd a sailing-Scheme, whereby Winds are imagin'd to be forms of Gravity acting not vertically but laterally, along the Globe's Surface.... All the possible forces in play are represented each by its representative sheets, stays, braces, and shrouds and such,--a set of lines in space.... Easy to see why sea-captains go crazy,--godlike power over realities so simplified" (220, emphasis added), and his real scientific resentments are about the creator's "lapses in Attention, the flaws in Design... the failures to be reasonable, or to exercise common sense" (220). Like differential calculus, fluxions allow for and underlie the simplification, operationalization, and capitalization of the world, and thus bring about its dis-enchantment and de-fictionalization; the fact that "the Flow of Water through Nature, along a Gradient provided free by the same Deity, might be re-shap'd to drive a Row of Looms" (207). On the other hand, as Wicks Cherrycoke suggests, fluxions open up a Christian hermeneutics that attempts--like Pynchon's prose--to "measure even That Which we cannot,--may not,--see" (721). As he states, "many of us in the parsonical work... find congenial the Mathematics, particularly the science of the fluxions. Few may hope to have named for them, like the Reverend Dr. Taylor, an Infinite Series, yet such steps, large and small, in the advancement of this most useful calculus, have provided us a Rack-ful of tools for Analysis undreamed-of even a few years ago, tho' some must depend upon Epsilonics and Infinitesimalisms, and other sorts of Defective Zero. Is it the Infinite that tempts us, or the Imp? Or is it merely our Vocational Habit, ancient as Kabbala, of seeking God there, among the Notation of these resonating Chains" (721). And, ultimately, even the Hollow Earth can be brought about in a precise topological manner through fluxions: "Consider. We've an outer and an inner surface, haven't we, which mathematickally, 'tis easy, using Fluxions, to warp and smooth, by small, continuous changes, into a Toroid, with openings at either end, leading to.... An Inner Surface? Are you by chance seeking analogy between the Human Body and the planet Earth? The Earth has no inner Surface, Dixon" (602). [12]

-

The most direct reference to chaos theory in

Mason & Dixon is

the reference to the possibilities of seemingly random change residing

in a chaotic system; a system that is, like history or a continent,

"sensitively

dependent on initial conditions." In an almost direct reference to Edward

Lorenz's image of a chaotic trajectory, which he illustrates by a ski-slope

(another image might be a the surface of a pachinko or a pinball machine,

both of which figure prominently in Vineland), Pynchon shows how

"Mr. Knockwood, a sort of trans-Elemental Uncle Toby, spends hours every

day not with Earth Fortifications, but studying rather the passage of Water

across his land, and constructing elaborate works to divert its flow....

'You don't smoak how it is,' he argues, '--all that has to happen is some

Beaver, miles upstream from here, moves a single Pebble,--suddenly, down

here, everything's changed! The creek's a mile away, running through the

Horse Barn! Acres of Forest no longer exist! And that Beaver don't even

know what he's done!'" (364). Pynchon relates this freedom of choice and

the possibility of "unaccountable" change to the chronology of human life,

relating it thus to the trajectory from youth to maturity--one might turn

Lorenz's image upside-down and write death at the bottom! Again, one might

refer to the tangled lines of history converging onto death as a final

attractor "on this side": "As if... there was no single Destiny... but

rather a choice among a great many possible ones, their number steadily

diminishing each time a Choice be made, till at last 'reduc'd,' to the

events that do happen to us, as we pass among 'em, thro' Time unredeemable"

(45). [13]

The most direct reference to chaos theory in

Mason & Dixon is

the reference to the possibilities of seemingly random change residing

in a chaotic system; a system that is, like history or a continent,

"sensitively

dependent on initial conditions." In an almost direct reference to Edward

Lorenz's image of a chaotic trajectory, which he illustrates by a ski-slope

(another image might be a the surface of a pachinko or a pinball machine,

both of which figure prominently in Vineland), Pynchon shows how

"Mr. Knockwood, a sort of trans-Elemental Uncle Toby, spends hours every

day not with Earth Fortifications, but studying rather the passage of Water

across his land, and constructing elaborate works to divert its flow....

'You don't smoak how it is,' he argues, '--all that has to happen is some

Beaver, miles upstream from here, moves a single Pebble,--suddenly, down

here, everything's changed! The creek's a mile away, running through the

Horse Barn! Acres of Forest no longer exist! And that Beaver don't even

know what he's done!'" (364). Pynchon relates this freedom of choice and

the possibility of "unaccountable" change to the chronology of human life,

relating it thus to the trajectory from youth to maturity--one might turn

Lorenz's image upside-down and write death at the bottom! Again, one might

refer to the tangled lines of history converging onto death as a final

attractor "on this side": "As if... there was no single Destiny... but

rather a choice among a great many possible ones, their number steadily

diminishing each time a Choice be made, till at last 'reduc'd,' to the

events that do happen to us, as we pass among 'em, thro' Time unredeemable"

(45). [13]

- Against openness and unaccountability, the project of the line is to reduce to certainty. As Cherrycoke notes, "Conditions hitherto shapeless are swiftly reduc'd to Certainty" (636). Ultimately, it is "out There, the Timeless, ev'rything upon the Move, no pattern ever to repeat itself" against the order of the straight line (209). Maybe even more than Mason and Dixon's respective journeys, the utopian counterweight to linear history and to control is thus the multiplex, differently "timeless" moment in its sheer complexity and potentiality; the moment traversed by "the tangle of purposes" (79). [14]

- During the passage from the Northern to the Southern hemisphere--always a crucial moment in Pynchon's fictions--Mason & Dixon experience: "the Gate of the single shadowless Moment" (56). Similarly, the second transit of Venus is seen in the context of the "Purity of the Event" (247), a moment, as Mason states, "redeem'd from the Impurity in which I must ever practice my Life" (247). History, like narrative in general, zooms in onto such pure events, which, in Pynchon's universe, are invariably promises: "the Event not yet 'reduc'd to certainty,'... [a] last moment of Immortality" (177). In particular children are (quite literally, because they do not yet know death and are thus "eternal and free" [701, my emphasis]), immortal and eventual. They still "jump, flapping their Arms in unconscious memory of when they had wings" (296). As such, the young "allow their Elders release, if only for moments at a time, from Its [Death's] Claims upon the Attention" (37). The innocence of children is also "The Innocence of Unconsciousness" (759). For the adults, a return to childhood is possible only as a (once more Deleuze & Guattarian) "becoming-child," or a "becoming-animal."¶ Culturally, the American West has always promised such an unconscious innocence, which is a topos as old as America itself, while the East figures the way "into Memory, and Confabulation" (618). Mason and Dixon's journey further West, therefore, is only a subjunctive; an "if" taken up by the narrative itself, which can imagine their going further West only as subjunctive, "conditional" projects and dreams. (See in this context the many "embedded subjunctives" such as: "All subjunctive, of course,--had young Mason gone to his father, this might have been the conversation likely to result" (208). It is Mason's & Dixon's (but also, in a sense, the narrative) line that "ifs" these other worlds. If they had, and the narrative with them, gone on "Westering" (711), Mason & Dixon might have reached the state of "becoming animal": "Supposing Progress Westward were a Journey, returning unto Innocence,--approaching, as a Limit, the innocence of the Animals" (427) and the narration might have reached silence. But they re-turn, like Mason from his journey into the eleven days, Dixon from the Hollow Earth, and the narrative from the idea of giving itself up to silence. [15]

- With Mason & Dixon, Pynchon has created a complex of (more or less) subjunctive worlds, all suspended between fact and fiction. A multiplexity of real:ized stories (stories transferred from Deleuzian "virtualities" into--if only written--"actualities"). In his retrospection of the genesis of America, he has charted out the complex discursive and topographical spaces which would build themselves up, according to a "logic of emergence," into the construct, or better aggregate, called America. In surveying a multiplex, turbulent space rather than excavating a point of origin, he affirms the underlying multiplexity--the tangle and the knot--on which all orders--lines--are constructed. Charting the climate of (not only!) America during its beginnings, he also affirms the belief in America as a "far from equilibrium" system in which change--and chance--still have their place.¶ In the complex narrative intertwinings of chaos and order, rationality and irrationality, fact and fiction, trauma and jouissance, Pynchon refrains, as always, from easy, "predictable" answers. He never argues on just one side, although one can easily detect inclinations and "attractions" (which point to a neo-materialism, to eco:logics, and to subaltern studies, amongst others): His "pachinko poetics" remain fundamentally möbial, ambivalent and, in the best sense of the word, turbulent, as turbulent as the life-stories of C. Mason & J. Dixon. [16]

Dept. of American Literature and Culture

University of Cologne

hanjo.berressem@uni-koeln.de

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2001 HANJO BERRESSEM. READERS MAY USE

PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S.

COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED

INSTITUTIONS MAY

USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN

ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR

THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A

SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE

AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE

AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A

TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE.

FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER

VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO

PROJECT MUSE, THE

ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.