The Body of the Letter: Epistolary Acts of Simon Hantaï, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Jacques Derrida

Julie Candler HayesUniversity of Richmond

jhayes@richmond.edu

© 2003 Julie Candler Hayes.

All rights reserved.

- In the summer of 1999, Jean-Luc Nancy wrote to the artist Simon Hantaï with a request: to produce a work that might be used as the frontispiece of a forthcoming book on Nancy by their mutual friend, Jacques Derrida. Hantaï responded enthusiastically and set to work on a series of "unreadable manuscripts," meticulously written and re-written on fine batiste, stiffened, crumpled, and folded. Derrida's Le Toucher, Jean-Luc Nancy, accompanied by black and white photographs of Hantaï's "travaux de lecture," appeared in early 2000, but the exchange of letters between Hantaï and Nancy continued for several months. In late spring, Nancy asked Hantaï to consider the publication of their letters; a year later, La Connaissance des textes: Lecture d'un manuscrit illisible (Correspondances) appeared, with the text of the correspondence, full-color plates of Hantaï's "travaux de lecture," photographic reproductions of all the letters, and a final letter by Derrida addressed to both correspondents.

- I propose a reading of La Connaissance des textes that takes into account its epistolary dynamics: its logic of sending and receiving, its "message strategy," its complex negotiation of visual and discursive modes, and its relationship to a set of significant pre-texts--the passages from Nancy's Etre singulier pluriel and Derrida's Donner le temps that Hantaï laboriously renders "unreadable" in his haunting works--and, of course, Le Toucher itself. Furthermore, I want to look at La Connaissance des textes not only as a "text," but also as a "book": a physical object, manifesting production constraints and editorial choices that subtly interact with the dialogue of the correspondents.

- Epistolary discourse has long been a site for reflecting on the paradoxical entwinement--particularly, though

not exclusively, inasmuch as letters bespeak affect, passion--of bodies and words, embodied words. In earlier forms of

epistolarity, the materiality of letters (the physical state of paper and ink, the letter's trajectory through space)

reinforced the impression of incarnation. Even in the apparently abstract medium of fiber-optic-borne email, we concoct

means to preserve this connection. Letters intrigue us because they ultimately tell us a great deal about writing, and

reading, as such. Epistolary writing is productive, or "machinic," in a Deleuzian sense; it exceeds attempts to reduce it to

a function of absence, to a uni-dimensional communication circuit, or to a univocal meaning. In this reading, I would like

to explore first Simon Hantaï's "unreadable manuscripts" themselves, then the complex folds of the correspondence, its

machinic qualities and resistance to closure, the physicality of the letters, and the questions of reproducibility and

readership that arise in connection to the production of the published correspondence. Last, I will look at the "late

arrival" in the exchange, Derrida's concluding letter-essay on "intimation."

I. "Travaux de lecture."

- Born in Hungary in 1922, active in France since the late 40s, Simon Hantaï experimented with different

techniques as he engaged first with surrealism and then with the expressionism of Jackson Pollock. 1960 is often seen as a

turning point in his work, with the emergence of "folding as method" (le pliage comme méthode) that he has

explored in one form or another in the decades since: canvases folded or crumpled, painted or written upon in different

ways, stretched or left folded. As Hantaï writes to Nancy,

As I've already written somewhere, something happened through and in painting--line, form, colors united in a single gesture (after the long history of these questions). Scissors and the stick dipped in paint. Folding was an attempt to confront the situation.[1] ¤

After decades of successful exhibitions, including a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 1976 and the 1982 Venice Biennale, Hantaï ceased exhibiting for 16 years, preferring to study, to read, and to pursue his art away from public view until the late 90s.[2] Of his most recent work, the Laissées, a group of folded and collaged canvases incorporating pieces of earlier work, critic Tom McDonough writes:"Comme j'ai déjà écrit quelque part, quelque chose est arrivé par et en la peinture--ligne, forme, couleurs réunies dans un seul geste (après la longue histoire de ces questions). Les ciseaux et le bâton trempé. Le pliage essayait de faire face à cette situation." "They are perhaps the finest achievement of his career to date, works which embody the great themes of the visible and the invisible, the revealed and the hidden, the painted and the unpainted. . . . The programmatic denial of painterly proficiency evident throughout Hantaï's mature career reaches its acme in these pieces, where the artist never picks up the brush. Scissor replaces brush, and collage is not, as in Matisse, placed in the service of painting, but is rather instated at its heart, as a challenge to be met."[3]

- Thus, when Nancy writes to Hantaï inviting his collaboration on Le Toucher (5 July 99; 25),

the painter writes back to propose a work of ink on paper, copying passages from both Nancy and Derrida, recalling an earlier

project based on la copie, "une peinture-écriture" from 1958: "Copying interminably, one over another, to the

point of unreadability, where a few words spring out of the chaos" ¤ (9 July 99; 27). A day later, he writes again with a second proposition involving different techniques of pliage (and enclosing a photo showing a 1997 unearthing, défouissement, of paintings buried in his garden). Nancy responds enthusiastically, noting that "folding is making something touch" ¤

"Copier interminablement, une sur l'autre, jusqu'à l'illisibilité, où quelques mots surgissent du chaos" (39). With the approval of Derrida and Michel Delorme, director of the publishing house Galilée, Hantaï sets to work."plier c'est faire se toucher" - The pieces that result are a set of five large "travaux de lecture"[4] on

batiste that has been treated, folded, and stiffened to become a writing surface on which Hantaï painstakingly copies

and recopies passages from Donner le temps: 1. La fausse monnaie and Etre singulier pluriel,

stopping just short of the saturation point, in a process bewildering to eye and mind--"disconcerting abracadabra

experience," ¤ as he later calls it (61). One of the five, ultimately, will be unfolded and stretched, so that multiple irregular swaths of white cut through the fields of writing; a detail appears as the frontispiece of Le Toucher.[5] Nancy's first reaction to photographs of the work-in-progress emphasizes the dizzying effect of textual dissolution through repetition, saturation:

"déroutante expérience d'abracadabra"

Nancy points out that the project unites Hantaï's signature pliage technique with the "calligraphic" elements of a painting that is considered a turning point in his career, just prior to the emergence of pliage: his 1958-59 Ecriture rose.[6] The passages Hantaï chose to copy--to present and to make disappear--offer important resonances, new folds, and implications both for the travaux and for the correspondence.[7]here is a never-before edited text or a text edited as never before... Or rather, unheard-of, if you definitively bury in those folds the sonority of the voices that would have uttered these words, making the words disappear along with their meaning, their voice (voces), leaving nothing to touch but their crumpled and pressed traces, stuffed into the cloth that ends up eating the text.... Because it's about Derrida, about a touch among you, Derrida, and me--one could say without forcing it, without giving an illustrative interpretation, that you replay the game of his "writing" but referring it elsewhere, displacing it toward what you've just suggested to me: the cloth eats the text (which is itself textile). (15 Aug. 99; 59) ¤

"voilà du texte jamais édité ou édité comme jamais . . . Ou bien, inouï, si vous enfouissez dans ces plis, définitivement, la sonorité des voix qui auraient prononcé ces mots, faisant disparaître aussi les mots avec leur sens, leur voix (voces), ne laissant à toucher que leur traces froissées, pressées, enfoncées dans le tissu qui finit par manger le texte.... Puisqu'il s'agit de Derrida--d'un toucher entre vous, Derrida et moi--on peut dire sans rien forcer, sans faire de l'interprétation illustrative, que vous rejouez toute la partie de son "écriture" mais en la rapportant encore ailleurs, en la déplaçant vers ce que vous venez de me suggérer: le tissu mange le texte (qui est lui-même tissage)." - In his initial proposal, Hantaï announces that he will choose to copy "a text already written lending

itself (implicitly or explicitly) to dispersion" ¤ (26 July 99; 43). The passage from Donner le temps includes part of a long footnote proposing a rereading of Heidegger's "Anaximander Fragment" in terms of three interconnected themes: the gift, the hand, and the logos (201n.). The main text is Derrida's reading of the final part of Baudelaire's prose poem, "La Fausse monnaie," the logic of which involves the touching, or contamination, of two economies distinguished by Aristotle as the khrema--that is, limitless (and illusory) potential of commerce--and the oikos--that is, domestic economy of (healthy) finite exchange. As Derrida points out, the "gift" of a counterfeit coin in Baudelaire's ironic fable points toward a phantasm of limitless power (the khrema), and ultimately to the dissociation of the "gift" and the principle of generosity: "the gift, if it exists, must go against or independently of nature; breaking, at the same time, at the same instant, with all originarity, with all originary authenticity" ¤

"un texte déjà écrit (implicitement ou explicitement) ouvrant à la dispersion" (Donner le temps 205). Even in the moment when he believes himself to have understood his friend, the giver--and condemned him as "unpardonable"--Baudelaire's narrator fails to "see" his own speculation, his own credulity, his own misunderstanding of both gift and pardon."Le don, s'il y en a, doit aller contre ou sans la nature, et rompre du même coup, au même instant, avec toute originarité, avec toute originaire authenticité" - The passage Hantaï chooses from Nancy falls within a discussion of a passage in Heidegger's

Beiträge, through which Nancy develops the possibility of a "co-existential analytic" or pre-comprehension of

meaning, sens, in terms of relation, being-with, "the originary plural folding" ¤ (Etre singulier 118). There follows a dense unfolding of what is already a dense passage in Heidegger (Derrida will cite part of it in his afterword to Connaissance, 151-52), elaborating the profound "with-ness" within self, an originary "mediation without mediator" which itself does not "mediate," but is simply the space between, "half-way, place of partaking and passage" ¤

"la pliure plurielle de l'origine" (Etre singulier 119).[8] Ultimately, Nancy argues, the structure of "self" is the structure of "with"; solipsism is singulier pluriel (Etre singulier 120). He will go on to interpret the being of Dasein, être-le-là, in terms of this new value of being, être, as "disposition," simultaneously separation, écart, and proximity (Etre singulier 121)."mi-lieu, lieu de partage et de passage" - In the passage chosen by Hantaï, Nancy announces the need to "force a passage" within Heidegger's existential analytic in order to give greater prominence to the notion of mitsein that Heidegger subordinates to it. Nancy argues for a rereading--or a rewriting--of the German philosopher that gives primacy to "being with." His close reading of a passage in the Beiträge is a masterful unfolding, explication, of the text: reading not only "with" Heidegger but also through him, in the interstices, an elaboration of the text that is also a dialogue with it. It is worth noting that Nancy prefaces the discussion in the paragraph immediately preceding Hantaï's passage by articulating his own relationship to Heidegger (Etre singulier 117), a relation that is neither one of facile antagonism nor docile sectarianism but rather something between or beyond, and always in progress.

- Read together--a phrase that takes on new meaning in the context of Hantaï's work--these texts

add to one another in unexpected ways. Both are close readings, replications and explications of other texts: Baudelaire,

Heidegger. Both propose, within the textual fold of a footnote, a rereading or rewriting of Heidegger, which neither

actually carries out, although Derrida sketches his in further.[9] In the course of his

correspondence with Nancy, Hantaï suggests several times that he will reveal his thinking on the two passages; he had,

in fact, been rereading Etre singulier pluriel prior to Nancy's invitation, and one of the earliest letters in

the series includes a series of questions about specific passages in the book (7 Apr. 99; 19). In the end, however, he

confines himself to alluding to a "troubling experience of these modifications in reading" ¤ (12 Aug. 99; 55) and elsewhere to a profound "disorientation" provoked by the "differences" between the two texts (6 Sept. 99; 69).[10] Of Hantaï's experience in copying I will say more in the discussion of the letters, but I would like to linger a bit more on the relation between the two texts, forever embedded in one another in the travaux, yet increasingly distinct from one another in the artist's mind. Certainly, Nancy's passage offers a much more "immediate" connection to the works; its complex situating of relation at the heart of identity bespeaks the "with-ness" of the travaux, which visually blur textual boundaries and distinctions even as they maintain them, cohesive yet fragmented, the contacts both reinforced and threatened by the folds in the writing surface. As Nancy writes elsewhere, "no contact without separation" ¤

"expérience troublante de ces modifications dans la lecture" (Corpus 51). Derrida's reflections on the gift have a clear, if startling, relation to the travaux which are created in response to friendship and become literally a gift when Hantaï mails all five works to Nancy in Strasbourg in March 2000. Derrida too is concerned with a space between, with the permutations of relationality implicit in the khrema: "to require, to need, to lack, to desire, to be indigent or poor, then duty, necessity, obligation, need, usefulness, interest, thing, event, destiny, demand, desire, prayer, etc" ¤"pas de contact sans écart" (Donner le temps 201). To which one might add, "intimation," his term for the disorienting experience of reading the correspondence, as we shall see."il faut, avoir besoin, manquer, désirer, être indigent ou pauvre, puis devoir, nécessité, obligation, besoin, utilité, intérêt, chose, événement, destinée, demande, désir, prière, etc." - In Derrida's reading of Baudelaire, the khrema is initially introduced as the "mauvais

infini" threatening the stability of domestic exchange (Donner le temps 200), but it is quickly shown to be the

operative law of exchange, radicalized by a notion of absolute gift. A "gift" cannot be grounded in "generosity" nor pardon

in any form of "merit," for such grounding limits the freedom of the act. As Baudelaire's narrator condemns his friend for

committing "evil from stupidity," ¤ Derrida nods briefly in the direction of Nietzsche and Bataille (205) and argues that the narrator has taken the side of desire and the will to knowledge, something "closer to the khrema than to the oikos" (212), finally identified as the Kantian Sapere aude, philosophical Enlightenment.

"le mal par bêtise" - Certainly the initial frameworks of these two passages are quite different: the narrator of "La Fausse monnaie" condemns his sometime friend without appeal, whereas "the violence of current events" lends a particular urgency to Nancy's being-with, formulated as exposure without alienation, as compassion.[11] The arguments are conducted quite differently as well, so that Hantaï would later say that even as he wrote and over-wrote the texts into a blur, they became increasingly distinct in his mind. And yet both the desiring infinities of the khrema and the hovering "singular plural" prior to existence, prior to beings, represent forms of inter-mediacy, or intermediality. And both are contained within the travaux de lecture.

- Deleuze saw analogies between Hantaï's work and Leibniz's theory of obscure perceptions,

according to which experience is composed of an infinity of microperceptions, our internal representation of the plenum, the

labyrinth of continuity; our ability to distinguish between objects and events is contingent on "forgetting" continuity,

selecting some aspects and letting others remain obscure: "microperceptions or representatives of the world are these tiny

folds in all directions, folds in folds, on folds, along folds, a painting by Hantaï..." ¤ (Le Pli 115).[12] As we look to the correspondence as a whole we can see a further analogy. The correspondence too is a complex network of question and answer, understanding and confusion, memory and forgetting. If we look closely, it becomes infinite and the act of reading interminable. Each letter is itself a "series" of intersocial and intertextual allusions of infinite depth, yet must remain part of a succession of (other individually infinite) moments. This is the logic of "plis dans plis." Just as monads obscurely bespeak the entire world, "even if not in the same order" (Deleuze 122), the quotations bespeak the works from which they came, which in turn point to other texts, other conversations; and the letters bespeak both the correspondence and an often obscure network of quotation, allusion, and speculation. Again speaking of Leibniz's "folds," Deleuze notes that "the unfold is never the opposite of the fold" ¤

"Les microperceptions ou représentants du monde sont ces petits plis dans tous les sens, plis dans plis, sur plis, selon plis, un tableau d'Hantaï" (124); once stretched, the unfolded canvas or cloth could not be reconstituted as folded, as the complexity of the process and the role of chance prohibit an exact repetition. The unfolded work emphasizes its own insertion in temporality and the (time) gap between writing and folding, even as it leaves open the possibility of further physical changes, new writing or folding. In the letters following the production of the travaux, Hantaï seems indeed to be contemplating further action. He refers to a "second phase" yet to come (69, 75) and after unfolding one piece hesitates as to the other four, still waiting, "en attente" (97): should they be further photographed? unfolded? rewritten? He refers to his work not as "finished," but rather as "abandoned" (n.d.; 119). Having "opened" only one piece and having ceased the work of copying just prior to the saturation point, Hantaï maintains his project "in progress," in-between, open to possibility, keeping its "with-ness" entire.[13]"le dépli n'est jamais le contraire du pli" II. "Comment peut-on lire une correspondance?"

- The dynamics of epistolary writing have been much studied in recent years. The implications of reading a missive originally addressed to someone else, while exploited in novels from Laclos's Liaisons dangereuses to Matt Beaumont's electronic frolic e: A Novel, also create disturbances for editors and readers of "real" correspondences, who must renounce seeing in letters simple "documents" of a particular time and place, and instead confront them as "texts" that are not always susceptible to complete explication or decipherability, but which nevertheless bear a different relation to the world than, say, the marquise de Merteuil's Letter 81.[14] In any event, the act of reading a published correspondence is inevitably shaped by a series of decisions and affective investments made by the editors and by the letter-writers themselves. In an earlier project I argued that one could see a correspondence as a "desiring machine," a system of libidinal ruptures and flows constructed from "marking" or selecting a correspondent; interpreting one's own letters as part of a series; "inscription and distribution" or elaborating interpretative strategies and writing "toward"; and "feedback" or rereading letters, letting their meaning shift recursively in addition to the ongoing processes of marking and inscription.[15] The machinic model is useful inasmuch as it provides an enabling conceptual vocabulary for coming to terms with a phenomenon that is both affective and social, patterned but not predetermined, and productive rather than stemming from "lack."[16]

- We can see these processes in the Nancy-Hantaï exchange as well: the book, La Connaissance

des textes, comes into being at a particular moment, in response to a particular set of circumstances. Letters have

already been exchanged, perhaps for years, presumably without either participant considering them as an exercise leading to

publication. "Marking" takes place in the manner that the correspondents define one another and come to see their

correspondence as having its own identity as a body of writing. The sequence of published letters begins in medias

res, with Hantaï's response to an earlier request from Nancy on the eve of a departure for a few days in his

country house.[17] The interlocutors' mode of address is amicable, respectful, and

collegial; part of the correspondence's "plot" is however the construction of a zone of more intimate friendship, underscored

most notably in the shift, at Nancy's request, to first names (the significance in the change is underscored by Nancy's

simultaneous expression of concern for the health of Hantaï's wife, Zsuzsa, "if she will allow me to name her thus" ¤ [15 Aug 99; 59]), but also by expressions of concern about each other's health, requests for news of family members, etc.[18] But if in other sets of epistolary circumstances the consolidation of protocols of intimacy is accompanied by a wish for privacy ("Burn the letter!"), in this case the opposite occurs, when Nancy proposes as early as 16 September 1999 to "faire quelque chose" with the letters (71). He returns to the suggestion in March 2000, emphasizing the importance of Hantaï's letters:

"si elle me permet de la nommer ainsi" we could gather our letters since the beginning of the work--"ours," that is primarily yours, the only ones that count (mine would provide the connections) and whose work that you've termed "of reading" is already itself a text and/or an over-script, an overstrike of the work on cloth.*

Singling out a thread in his "cellar" of correspondence, it is Nancy who creates the opportunity for the production of Connaissance, which becomes in effect a return gift, a portrait of Hantaï: "I wanted others to read these letters that show the painter-copyist at work" ¤[Nancy's footnote] If you haven't kept my letters it's not a problem--I have all of yours, assuming none has strayed (in general I keep all the mail I receive, absolutely all--it sleeps in the cellar). (123) ¤

"nous pourrions rassembler nos lettres depuis le début de ce travail-'nos, c'est-à-dire avant tout les vôtres, les seules qui comptent (les miennes feraient l'enchaînement), dont le travail de lecture, si je peux dire, de ce travail lui-même dit par vous 'de lecture,' est déjà par lui-même un texte et/ou une surcharge, une sur-rature du travail sur les toiles."*

[Note added by Nancy] "Si vous n'avez pas gardé mes lettres, c'est sans importance--moi, j'ai toutes les vôtres, si aucune n'est égarée (de manière générale je garde tout le courrier que je reçois, strictement tout--qui dort à la cave)."

(Connaissance 9).[19]"J'ai souhaité faire lire ces lettres qui montrent le peintre-copiste au travail" - The second component of the epistolary machine is the act of reading, interpretation, imbricated

within the act of writing. To focus on reading is to bring to light the complexity of the "communication" process, to recall

that not all questions are answered, or even understood, that any message encounters scrambling upon entering the zone of

associations and responses that constitute the reader. Letters cross in the mail; the disturbances in their delivery alter

their messages. Even when the letters arrive in order, their writers may write at cross-purposes, each missing what the

other is saying. Connaissance offers not only a "picture of the artist at work," but also any number of other

objects in the room, the significance of which varies according to the spectator. Take for example Hantaï's typically

elliptical reference, in his letter of 6 September 1999, the letter announcing the "end" of his copying: "Seeing the allure, the

illuminating tendency (book of Kells) in Derrida, in bricks of material in you" ¤ (69). Nancy, the conscientious reader, asks in his next: "You write parenthetically '(book of Kells)'--and I don't know what that is" ¤

"Vu l'allure, la tendance enluminante (livre de Kells) chez Derrida, dans des briques de matériaux chez vous" (71), only to receive an even more perplexing answer:"Vous écrivez entre parenthèses '(livre de Kells)' --et je ne sais pas de quoi il s'agit"

In his next letter, Nancy tries again: "There's an allusion I don't understand: 'Book of Kells etc. etc. are ellipses...' Is it a title I'm forgetting?" ¤Book of Kells and etc. are ellipses. I wanted to talk about the differences that appeared in that zone of indifference, once preference, predilection, ground up as well. I couldn't write about it without getting into a polemic. Experiences before choice, without judgement. Predilections stripped naked. Fields ploughed endlessly, stones and boulders coming up from below, ploughshare running into the singularities of their weight and their voices. (15-19 Sept 99; 77) ¤

"Livre de Kells et etc. sont des points de suspension. Je voulais parler des différences apparues dans cette zone d'indifférence, une fois la préférence, la prédilection, broyée aussi. Je n'arrivais pas à en écrire sans ouvrir une polémique. Expériences avant le choix, sans jugement. Prédilections dénudées. Champs labourés sans fin, pierres et blocs remontant du fond, heurts du soc et les singularités de leur poids et de leur voix." (n.d.; 81). The answer comes months later, in a long letter that Hantaï dates 28 November-17 December, when under a postscript headed "Retouches," he picks up this and other loose ends: "Book of Kells, like the Saint-Gall lectionary, manuscripts with pictures, stylized ornamentation, Irish, seventh century" ¤"il y a une allusion que je ne comprends pas: 'Livre de Kells etc etc. sont des points de suspension...' C'est un titre que j'oublie?" (103). While banal in appearance--Hantaï realizes only belatedly that Nancy sought not an ontological explanation for his allusion, but merely a gloss--this side exchange shows the fluidity and unpredictability of both reading and writing. What begins as an evocative metaphor--Derrida's text imagined as an illuminated manuscript--becomes in its repetition an emblem of Hantaï's physical and mental exhaustion in the weeks immediately following cessation of the travaux, of the impossibility of articulating the differences that he "felt" between the two texts in the course of his work. The initial sketch of a comparison--Derrida as "enluminure," Nancy as "briques de matériaux"--suggests not, I think, a comparison between "decoration" and "substance" (hardly in keeping with either Hantaï's or Nancy's relation to Derrida!), but rather a perception of two very different forms of complexity, different forms of internal organization, as much between the ways of engaging the prototexts Baudelaire and Heidegger as between the manifold khrema and the pliure plurielle de l'origine."Livre de Kells, comme l'évangéliaire de Saint-Gall, manuscrits à peintures, ornementations stylisées, irlandais, VIIe siècle" - The work of interpretation in Connaissance is given additional depth inasmuch as both

correspondents are engaged in "dialogue" with the travaux themselves: Hantaï most directly, of course, but

Nancy through the photographs Hantaï sends and the (telephonic) accounts he receives from Derrida and Michel Delorme,

both of whom visit Hantaï and observe the work in progress. (Nancy's one projected visit is cancelled because of

illness, prompting Hantaï to ship all five travaux to his home in Strasbourg.) Certainly the heart of the

correspondence lies in Hantaï's accounts of his work: the initial choice of materials (9 Aug. 99; 53); the early stages

of the work:

(Nancy responds to this letter, and its accompanying photographs, with the observation cited above, "le tissu mange le texte," and the request to call Simon Hantaï by his first name.) On 9 September (the "Book of Kells" letter), Hantaï announces that he's stopping, although for the moment he does not exclude the possibility of further works in the series, or a "deuxième phase." This letter and those following, however, emphasize his mental state: "I am also stopping from fatigue and especially from disorientation" ¤I'm coming to a first stage of saturation that I've already told you about. There are threshholds of saturation, tidelines. Time passes, I write, nothing seems to move. But soon signs appear (strokes accumulating on one another, next to one another, heading toward marks, toward another picturality). (12 Aug. 99; 55) ¤

"J'approche vers une première étape de cette saturation dont je vous ai parlé déjà. Il y a des seuils de saturation, limites de marées. Le temps passe, j'écris, apparemment rien ne bouge. Mais bientôt apparaîtront les signes (les traits accumulés l'un sur l'autre, l'un à côté de l'autre et iront vers des taches, vers une autre picturalité)." (69). A week later: "Coming back to the stop: I was at the end. Uselessness of dancing trinkets. Vacuity. Indifference. Sitting on the doorstep, seeing only the effects of light coming through the holes between the leaves..." ¤"J'arrête aussi par fatigue et surtout de désorientement" And, describing the act of copying: "At the beginning, in spite of some uneveness in the surface, the pen glides, the eye looks ahead and helps overcome obstacles, the written text is readable. After going back over it hundreds of times, the eye's no longer good for anything, the pen gropes and bumps almost without interruption, breaks the words and the letters" ¤"Revenant sur l'arrêt: j'étais vraiment au bout. Inutilité de ces bibelots dansants. Vacuité. Indifférence. Assis sur le seuil de la porte, ne voyant que des effets de lumière traversant les trous entre les feuilles..." (15-19 Sept. 99; 75).[20]"Au début, malgré une certaine inégalité de la surface, la plume glisse, l'oeil prévoit et aide le franchissement des obstacles, le texte écrit est lisible. Après des centaines de passages, l'oeil n'est plus bon à rien, à l'aveugle, la plume tâtonne et bute presque sans discontinuité, casse les mots et les lettres" - Short exchanges of ideas and photographs follow. In late November, however, Hantaï begins

writing a long letter that he will continue over two weeks, a remarkable text recapitulating "the work of the copyist,

banal, humble, and stupid, that I undertook at your request" ¤ (28 Nov.-17 Dec.; 95). He describes the camera work on the details to be used for Le Toucher--reproducing, making visible the travaux--even as he explains his project as a "decanonization of the privilege of sight" ¤

"Le travail de copiste, banal, humble et bête, que j'ai entrepris à votre demande" (97).[21] The disorientation of vision leads to an altered apprehension of the texts and a loss of connections, of meaning: "modification of the articulations touching its matter, rupture and reconnection constantly modified, redislocated, contact interrupted, lost, etc." ¤"découronnement du privilège de la vue" (101). And last: "I don't know where I am" ¤"Modification des articulations qui touche à sa matière, brisure et raccordement continuellement modifiés, redisloqués, contact interrompu, perdu, etc." (103). Physical illness intervenes in the month that follows; Hantaï writes again in February, his mood bleak following a severe fever, to announce that he is abandoning his project of a book for Gallimard: "Affirmation of a fall. Cutting off, spacing, dislocation, dispersion, the senses unbound, without relation, outside any possible relation, unbridgeable cut, irreparable" ¤"Je ne sais pas où je suis" (16 Feb 00; 108). Hantaï's intense concentration on the two texts that seek to evoke a "space between" appears to have taken him deep into that space, to the point that its "edges," the point of articulation, are no longer clear.[22] While expressing his delight over the new set of photographs, Nancy becomes concerned: "Your note is so painful" ¤"Affirmation de chute. La coupure, l'espacement, la dislocation, la dispersion, les sens déliés, sans relation, hors de tout rapport possible, coupure infranchissable, irréparable" (n.d.; 113). Shortly thereafter, he offers a reading of the travaux that may serve as well to help restore their maker, affirming both the "coupure" and the "lissée" as well as the "faire" in "faire voir," reading the travaux as "work," "ouvrage contre l'oeuvre,"[23] rather than a space of disintegration, and asking Hantaï to reflect a bit on their "musical" qualities (6 Mar. 00; 118). At this point, Hantaï ships the works to Nancy. Nancy asks again to publish the correspondence (in terms that imply that he has already made plans with the publisher: "I know that Galilée would be ready to do it" ¤"Votre mot est si douloureux" [21 Mar. 00; 125])."Je sais que Galilée serait prêt à le faire" - The painter emerges from his dolorous withdrawal, or perhaps simply recovers from his earlier

debilitating fever ("what was I thinking?" ¤ [29 Mar. 00; 129]). His final evocation of his "expérience de copiste" foregrounds connections, not disjunction ("connected worlds, hyphens, lines of synthesis, of communication..." ¤

"Où avais-je la tête?" [133]). From this point on, the letters turn to questions of publication and reproduction. The title--or titles--chosen for the collection, La Connaissance des textes: Lecture d'un manuscrit illisible (Correspondances),[24] emphasizes the centrality of reading, and its paradoxes--understanding and misunderstanding, reading and unreadability (or reading as evacuation, even pain, and reading as restorative), the partitions of private experience and their overcoming--all overwrite one another as the two correspondents seek to comprehend their relation to one another and to the work of art.[25]"les mondes reliés, les traits d'union, de synthèse, de communication " - The third major component of the letter-machine, recursive rereading and feedback, is most evident in

correspondences that take place over a long period of time, where the correspondents have occasion to rethink the relation

between past and present. A friend tells me, for example, that years earlier he had a life-changing experience, a dream, of

which I knew nothing at the time; I reread his letters, weighing them anew, and reconsider the present in the light of the

altered past. At its painful extreme this reconsideration becomes what Proust called l'ébranlement du passé

pierre à pierre. In the present instance, a simple reading might lead to a simple attribution of meaning: the

story of the making of the travaux, for example, or of the painter's struggle with the fundamental incompatibility

of the lissée and the coupure, and subsequent reemergence, whole, but not untouched by the

experience.[26] Such is the mobility and complexity of the acts of reading within

Connaissance, however, that we are deterred from assigning it a single narrative. The recursive reading occurs

most clearly perhaps in the letter appended by Derrida--the one letter intended from the outset for publication--that asks

the question, "how can one read a correspondence?" ¤ In the process of elaborating--or intimating--an answer, Derrida points to the "literariness" of one of the most unstudied of all the letters, Hantaï's note of 15 June 1999, written on the eve of his departure for Meun, "to stretch out in the grass and cut a passage through the weeds and treat the quince tree" ¤

"Comment peut-on lire une correspondance?" (13). The letter is already part of a chain, yet something prompts the correspondents-become-editors to choose it as Letter I, leading Derrida subsequently to marvel over its appropriateness (an appropriateness constructed retrospectively in the light of his own Wordsworthian associations): "how did you know the turn it would take, all the way to publication?" ¤"m'allonger dans l'herbe et tailler un passage dans les herbes folles et traiter le cognassier" (148).[27] The quince tree, le cognassier, quickly extends its ramifications of metaphorical association and personal recollection throughout Derrida's essay. At what point does a letter in an indefinitely structured series become Letter I? Only when one is seeking something that responds at some level to that which comes later, and even then the meaning of the individual letters changes with every rereading. The machinic syntheses at work, à l'oeuvre, in a correspondence cast into clear relief the productive nature of epistolary writing, which is not really about absence (as has often been claimed), anymore than a letter can be reduced to a single unvarying meaning or its author to a stable unchanging subject."comment saviez-vous le tour que tout cela allait prendre, et jusqu'à la publication?" - A correspondence is also an object, or set of objects and material practices. In a recent study of "the postal system," Bernhard Siegert has examined how the "materiality of communication" has informed modern subjectivity, transforming knowledge from a set of static "places" into messages sent and received. From the initial marking or delimitation of sender and receiver, through technical innovations such as the rise of delivery services and the invention of the postage stamp, the postal system rationalizes emergent authorial, libidinal impulses and directs their energy into communications networks. As such, the writing of letters (whether love letters, fan mail, letters of condolence or complaint, letters to elected representatives, to Santa Claus, or to Mom) participates in the disciplinary and rationalizing processes of modernity, producing postal subjects who always arrive at their destinations. While I admire Seigert's work very much for its meticulous reading of cultural history, I do not think that we can discount the unruly and unpredictable potential of epistolarity, the changing labyrinth within the grand system, the letter that contains the potential for not arriving (Derrida, La Carte postale 135). That the rational system contains the necessary preconditions for the emergence of the epistolary subject does not reduce that subject to the "law of the postal system." Electronic and digitized modes of communication have not radically transformed this situation, though certainly they have provided new sites for reflecting on its wider implications, as we see in The Telephone Book, Avital Ronell's exploration of the analogies between communications technology and Heidegger's "call." Yet, in spite of this work's startling typographic metamorphoses, its playfulness, cross-chatter, and interruptions, I wonder if the underlying point isn't ultimately a conventional, reassuring one, in which the message sent is finally received and the visual and discursive anomalies prove to have their elegant conceptual parallels. The postal system, indeed. Even so, Ronell brings out the strangeness of the rational system itself, its schizophrenic core.

- While equally as impressive visually, nothing could appear further removed from the graphic

eccentricities of The Telephone Book than the exquisitely documented correspondence of La Connaissance des

textes, whose material qualities I would now like to consider. Each letter appears both in print and in photographic

reproduction, accompanying the superb color plates showing details of the travaux de lecture. During the

discussion of

publication within the correspondence, Nancy conceives an even more ambitious plan. Under the initial euphoria of seeing the

travaux, he comes back to his idea to "faire quelque chose" with the letters: "I imagine a book in which there might

be at least one page of batiste thus treated... Is it imaginable?" ¤ (21 March 00; 123). Hantaï's reply is practical and realistic, asking whether the purpose is to create a collector's item or a book affordable by all:

"J'imagine un livre dans lequel il pourrait y avoir au moins une page de batiste ainsi travaillée... Est-ce imaginable?"

Hantaï emphasizes that this is not a refusal, simply an attempt to "situate the real questions." He wonders about other technical solutions: "A piece of cloth folded and written upon, or a piece of cloth simply folded? I have an idea for a folded piece with a photo-engraving printed on it... Let's leave things be, almost without thinking of them" ¤Your wish, as I see it, is to multiply and distribute what you have in front of you. In a sense, there is only one copy, along with the letters. It is yours.... Your proposal comes down to this: a book with limited edition plates, expensive for collectors, originals produced a couple of hundred times, and this time for aesthetic reasons only, lacking the motivations, the unpredictable, copyist. This is impossible for me. (1 Apr. 00; 137) ¤

"Votre souhait, je le vois bien, est de multiplier et de distribuer ce que vous avez devant vous. Dans un certain sens, il existe un exemplaire unique, avec les lettres. Il est à vous . . . . Votre proposition aboutirait à ceci: un livre avec dans des tirages à part, payé cher par des collectionneurs, des originaux à fabriquer cent ou deux cents fois, et cette fois seulement pour des raisons esthétiques, sans les motivations, l'imprévisible, copiste. Ceci m'est impossible." (139). It is the final letter in the published exchange."Un morceau de toile pliée et écrit, ou un morceau de toile seulement pliée? Me vient ici l'idée d'une pliée et d'une photogravure imprimée là-dessus. . . . Laissons les choses travailler, presque sans y penser" - In the end, of course, photography and mechanical reproduction take the place of real cloth, real

writing, real folds, in the representation of the travaux. The four folded works, distinguishable by the

different colors of their ink, each appear in a series of six two-page color spreads appearing at regular intervals. (The

unfolded piece that appears as the frontispiece in Le Toucher is not reproduced in

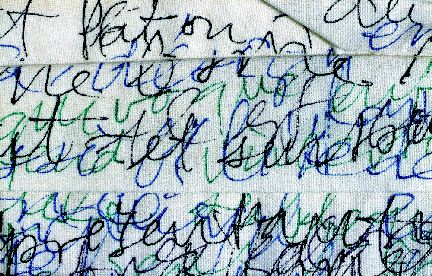

Connaissance.) Each series starts with a photograph of a section approximating life size (see Figure 1); the

details that follow successively zoom in at greater and greater magnification, "to go somehow beyond the eye," ¤ as Nancy puts it in his preface (9; see Figure 2): another form of the unsettling of vision.

"pour aller en quelque sorte au-delà de l'oeil"

Figure 1: Hantaï [blue-green-black] (Connaissance 78-79)

Images used by permission of Editions Galilée;

copying of these images is expressly forbidden.

Click for larger version of image.

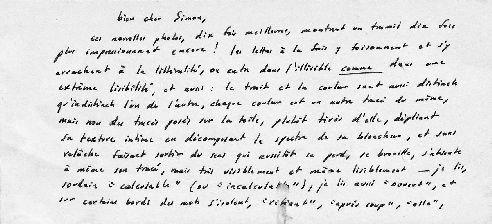

If readers of Connaissance are vouchsafed a view unavailable to the natural eye of the precise effects of ink amidst the filaments of batiste, they must nevertheless forego the most obvious part of the experience of an actual viewer of the works, seeing them each as a whole: the book offers only "details." Each of the letters is carefully reproduced, down to the scribbled legend on the back of a photo. We are able to appreciate Hantaï's "simultaneously round and angular ductus" ¤

Figure 2: Hantaï [blue-green-black] (Connaissance 104-05)

Images used by permission of Editions Galilée;

copying of these images is expressly forbidden.

Click for larger version of image.(91), the same handwriting that appears overwritten to unreadability on the canvasses, airily slanting up a page (see Figure 3) and contrasting with Nancy's own neat, concentrated script (see Figure 4)."ductus rond et anguleux à la fois"

Figure 3: Hantaï Letter

(Connaissance 94)

Images used by permission of Editions Galilée;

copying of these images is expressly forbidden.

Click for larger version of image.

Even the afterword, Derrida's letter-essay on "intimation," includes two photographed pages, rendering the set of "handwriting samples" complete. The availability of the manuscripts highlights the editorial work of the printed versions and reminds us of the editorial choices present in any published correspondence. Most of the changes are of a practical nature: obvious misspellings are corrected, and Michel Delorme's home phone number, visible in one letter, is discreetly left out of the print version. On the other hand, the transcription-edition of Hantaï's letters makes no attempt to render the complexity of their composition, the numerous crossings-out, the insertions, the self-corrections that suggest a constant process of self-reading and internal editing. Nancy's manuscript letters bear almost no evidence of revision and the reproduced sections of Derrida's essay similarly appear to have been written in a continuous gesture. The photographs of Derrida's manuscript point out one intriguing anomaly: whereas the "intimation" essay is punctuated periodically by bracketed ellipses ([...])--the conventional sign of an editorial cut--in at least one instance (and, one suspects, the others, but the entire manuscript is not reproduced) a comparison of print to manuscript versions reveals that no material was deleted.[28] The ellipses would appear to function as pauses, spaces between, virtual folds, in the text. Throughout all the letters, slippage, erasures, additions provoke questions but provide no answers regarding the status of the published letter and its relation either to its origin or to "truth."

Figure 4: J-L Nancy Letter (Connaissance 112)

Images used with permission of Editions Galilée;

copying of these images is expressly forbidden.

Click for larger version of image. - Handwriting, perhaps even the "hand" tout court, occupies a central place in

Connaissance. Certainly the travaux themselves offer a new twist on Hantaï's long-established

challenge to "the mastery of the gesture" (Pacquement 211) via folding and other techniques. Here, even in the complete

abandonment of brushwork, the artist's hand is more present than ever; Nancy sees a connection between Hantaï's "retour

à la calligraphie" and the great calligraphic traditions of China and the Islamic world (91). Given Nancy's initial

fantasy of a book that would include actual handwritten cloth, the final "mechanically reproduced" result would seem to imply

a loss of authenticity, or "aura," in Benjaminian terms: "a plurality of copies" substituted for "a unique existence"

(Benjamin 221). But, as Hantaï pointed out, even the fantasy book is just that, a fantasy, an illusion of authenticity;

he rejects the idea not because of the labor involved "a year or two of working with powder in the eyes" ¤ (137), but because the physical effort is no longer connected to "les motivations" that inspired the originals. The original travaux are the record and the product of a particular experience, "des traces de mon expérience de copiste" (137) and as such, irreproduceable ("il existe un exemplaire unique, avec les lettres. Il est à vous . . ." [137]).

"Un ou deux ans de travail de poudre aux yeux," - Even so, reproduction figures at the heart of the project. The originals are already copies and

the original experience an "expérience de copiste" in which the artist has undergone a complete evacuation of self and

sense, "to the point of dizziness and the exhaustion of indifference... Unforseen and rare gift received" ¤ (95). Even more to the point is the centrality of photography in the unfolding process: "the unfolding of the whole is profoundly linked to photography. The 'originals' are of little importance. They're just a support for other things on the way" ¤

"jusqu'au vertige et la lassitude de l'indifférence . . . Imprévu et rare don reçu" (28 Nov.-17 Dec. 99; 97).[29] In spite of his insistence on the aura of the singular artifact, Benjamin nevertheless admired still photography's ability to capture the specificity of a fleeting moment (226), as well as film's capacity to focus our attention via close-ups on "hidden details of familiar objects" (a function he likened to Freud's psychopathology of everyday life [235-36]). By concentrating on a particular moment, the photographs of the travaux evoke hidden potentials within folds, or a past process leading up to the unfolded state. As much might be said of the letters, carefully photographed in such a way as to emphasize the textures of the different kinds of paper and especially the creases: the proximity of the travaux helps us to see the letters, too, as unfolded works. So, if initially it might appear that the printed letters, like the photographs of the travaux, exist in a dependent relation of copy to original (or writing to speech), this relationship is unsettled: first, by the "essential" connection of photography and travaux; second, by the juxtaposition of the letters to the travaux themselves. Hantaï's manuscript letters are distinct from the travaux because they are more readable and because they represent the artist's own words, but the presence of the endlessly copied travaux remains to remind us that no word is ever entirely our own. Which is not to say that all letters are reabsorbed into the Postal System inflecting all consciousness. Rather, the travaux send us back to the letters, urging us to focus on the hidden details, the insertions and cross-outs, the perpetual process of reading and revising oneself, on the move, en route."Le déploiement de l'ensemble est lié essentiellement à la photographie. Les 'originaux' n'ont que peu d'importance. Ce n'est qu'un appui pour autres choses en route" - In his footnote reflecting on the relation of the gift and the hand in "La Fausse monnaie," one of

the passages embedded within the travaux, Derrida asks whether the relationship obtains "when money is so

dematerialized as no longer to circulate as cash, from hand to hand? What would be counterfeit money without a hand? And

alms in the age of credit cards and encrypted signatures?" ¤ (Donner le temps 203n.). To consider the present instance: what is handwriting without a hand? This is one of the key questions of Connaissance, a book that foregrounds--almost provocatively!--handwritten letters in the age of email. Part of the answer comes from the elision of the difference between original and copy that we have seen, the importance of the copy in the constitution of the original, which removes, in effect, the grounds we would have for privileging the actual paper, the actual cloth, of the "exemplaire unique." The other part comes from the capacity of the letters, of language, to "touch."

"quand la monnaie est assez dématérialisée pour ne plus circuler sous la forme de numéraire, de main en main? Que serait une fausse monnaie sans la main? Et l'aumône au temps de la carte de crédit ou de la signature chiffrée?" - As Nancy observes, Hantaï's project is about "un toucher entre vous, Derrida, et moi" (15 Aug

99; 59) as much as or more than it is "about" the book Le Toucher, whose progress to conclusion and through

production we follow in the letters.[30] It is Nancy who has articulated with particular

eloquence and "tact" the forms of touch that lie within and through writing.

The effect is all the more pronounced in words that flee material associations, whose medium is composed of oscillating digits, fiber optics, pixels; fragile, ephemeral, subject to immediate erasure, power shutdowns: handwriting without a hand.[31] Yet a sentence glowing on a computer screen can cause a body to double over in pain. Words touch us, enter into us, become embodied, become flesh. The extreme visibility of the handwriting in Connaissance, available only through photographic reproduction, serves to remind us of its absence, and thereby to remind us that the "touch" of writing is hardly dependent on a paper "base."[32] Hantaï: "painting does not depend on sight, nor music on hearing" ¤Whether we want it or not, bodies touch on this page, or rather, the page itself is touch (of my hand that is writing, of yours holding this book). This touch is infinitely detoured, deferred--machines, transports, photocopies, eyes, other hands have intervened--but there remains the infinitesimal stubborn grain, the dust of a contact that is everywhere interrupted and everywhere pursued. In the end, your gaze touches the same outlines of characters that mine touches in this moment, and you are reading me, and I am writing for you. (Corpus 47) ¤

"Que nous le voulions ou non, des corps se touchent sur cette page, ou bien, elle est elle-même l'attouchement (de ma main qui écrit, des vôtres tenant le livre). Ce toucher est infiniment détourné, différé--des machines, des transports, des photocopies, des yeux, d'autres mains se sont interposées--, mais il reste l'infime grain têtu, la poussière infinitésimale d'un contact partout interrompu et partout poursuivi. A la fin, votre regard touche aux mêmes tracés de caractères que le mien touche à présent, et vous me lisez, et je vous écris." (133)."la peinture ne dépend pas de la vue, ni de l'ouïe la musique" - "The paper falls away, leaving me with a cursor that turns itself into a tiny hand when it moves over

the email address of a distant friend: 'et vous me lisez, et je vous écris.'"

III. Intimations/Intimations

- In his concluding essay, addressed to both Nancy and Hantaï ("Cher Jean-Luc, cher Simon"),

Derrida promises to write "on intimation" (143), promising in language drawn from Hantaï's description of his

own work to make the word both "appear" and "disappear": "disparition par saturation." Intimation, the "law of intimation,"

becomes the guiding trope for Derrida's position as a reader of the correspondence of his friends. On the one hand, J.D.

being "implicated" throughout the letters, his comings and goings noted by both Nancy and Hantaï, "je sens venir quelque

intimation," a call or summons to respond. And yet the correspondence is complete without his intervention: "No reader will

ever change anything in this conversation 'between you' that will have taken place and that will remain unwitnessed." ¤ An intimidating situation, J.D. says, adding: "I prefer to stay in my corner." ¤

"aucun lecteur n'y changera jamais rien, à cet entretien 'entre vous,' qui aura eu lieu et restera sans témoin." The double summons--appear, disappear--is inscribed within the etymology of the word, "to intimate," which sends us both to juridical Latin, intimare, the injunction to appear, faire acte de présence, to acknowledge the (intimidating) power of the Law, and to the language of the heart, intimus, "l'intime, le dedans, le chez-soi" (145). Shifting between Latin, French, and English (a brief footnote refers us to Wordsworth's "Intimations of Immortality," which will play a leitmotivic role throughout the essay [145n.]), "the law of intimation" resonates in more than one language, sustaining both its mobility and its efficacity.[33]"je préfère rester dans mon coin." - The scope of the present essay does not allow me to follow every turn of Derrida's piece, which reflects his position as insider/outsider, reader/respondent, in what is in many ways a very literary reading of the letters, an examination of themes, allusions, structures, as well as the associations provoked by puns on phrases appearing in the letters: Hantaï/entaille (150n.) emerges during a reflection on "la coupure," and ver-à-soie/ soi takes us straight back to the passage from Heidegger's Beiträge discussed in the letters (and analyzed in Nancy's text in the travaux), which Derrida cannot resist citing in German, without further commentary: "Die Selbstheit ist ursprünglicher als jedes Ich und Du und Wir. . . ." (151).[34] The commentary takes us into the text from all directions; even the puns ask us to consider a passage into language created by pure sound, just as the travaux require us to "look" without reading.[35]

- I would like to focus on a set of recurring questions asked by Derrida: "How can one read a

correspondence? How can one read two friends at once? How can one address two friends at once?" ¤ (153). Despite the apparent specificity of his own implication in the exchange of letters, it should be clear that Derrida's situation is that of any reader of a correspondence: "excluded third party, late-comer." ¤

"Comment peut-on lire une correspondance? Comment peut-on lire deux amis à la fois? Comment peut-on s'adresser à plus d'un ami à la fois?" The same is true of any of us, since we need not share memories in common with the writers in order to be interpellated, intimated, touched by their words. How does one read a correspondence? Like this, mindful of the mutual engagement of Ich und Du und Wir, the "pliure plurielle de l'origine." As for addressing more than one friend at once, J.D. seems only able to alternate throughout the essay between "toi, Jean-Luc" and "vous, Simon."[36] And yet, at the same time, "how not to?" (153), for this is precisely the structure of intimation. "Intimation" is the name for IYouWe, the originary fold that is no static formation, but rather an ongoing injunction, a summons that enables me to read one friend when I am reading another, and to address them both when I address a single one. Although, as Nancy says, "touching on the body, touching the body, touching finally--happens all the time in writing" ¤"tiers exclu, tard-venu" (Corpus, 13), this capacity in all writing is nowhere more manifest than in epistolary writing. "Intimation" is the last of the "passive syntheses" of the epistolary machine: the place of the reader. We are different, distinct, but profoundly and irreducibly implicated in one another; in Nancy's terms, our "dis-position" with respect to one another is inseparable from our mutual "exposure." When someone enters a room and is instantly situated or "disposed" in relation to all other objects in the same space, that person is also "exposed": "he exposes himself: thus he is 'self,' or in other words he is--or becomes thus--as often and whenever he comes into the disposition" ¤"toucher au corps, toucher le corps, toucher enfin-arrive tout le temps dans l'écriture" (Etre singulier, 121). The "existential co-analytic" is vividly present in a correspondence, where both the urge to confess, to explain, and to justify oneself, as well as the opposite urge, the flight from intimacy and exchange, are forms of exposure, intimations, passions..."Il s'expose: c'est ainsi qu'il est 'soi,' c'est à dire qu'il l'est--ou qu'il le devient--autant de fois et chaque fois qu'il rentre dans la disposition" - In closing, Derrida asks two more questions. What happens to "l'intimation qui circule entre nous" once it has passed through "l'élément virtuel et quasiment liquide" of multiple computer screens? I take this as a late variant ("tard venu") on the question of the "dematerialized hand" in Donner le temps and as such, a question that was answered when the decision was made to photograph the letters. . . or earlier, perhaps, in Nancy's evocation of the "coming into presence" ("venue en présence") (and the "glorious materiality of coming"--matérialité glorieuse de la venue) of moving images on a television screen (Corpus 57). Every screen is a "touch screen," an intermedial limit that simultaneously separates and connects.

- Derrida's second question also echoes earlier queries. Are these letters and travaux really

readable, he asks, "readable without the law of the texts therein incorporated, encrypted, vanished, prescribing this or that

reading, this or that rewriting?" ¤ (154). In other words, can we read these letters without fully explicating their every fold, every reference from Aristotle to Merleau-Ponty? Derrida answers: "Non. Mais oui." And he proceeds to offer us a spectacular vision:

"lisible sans la loi des textes qui s'y incorporent, encryptent, disparaissent en nous prescrivant telle ou telle lecture, telle ou telle réécriture?"

As we earlier saw in discussing Deleuze's "plis dans plis" in Leibniz, the series is infinite, including as it does not only the history of philosophy evoked by Derrida, but the full range of textual microperceptions, nuances, events. The infinite series is an invitation to read, a summons or an intimation, to which, as readers, we can only respond.An order might be given us to proceed to a reversibility test: to bring forth, reconstitute, restore, from the transmutation to which you submitted them, Simon, the body of the text, the whole, articulated, readable words, the sentences with their meaning. Unless we were to give the order, without really believing it, to any potential reader. Perhaps that's the meaning of your titles, The Knowledge of texts. Reading of an unreadable manuscript, or rather, I myself would say, "the quince tree of manuscripts." (154) ¤

"Ordre nous serait donné de procéder à une épreuve de réversibilité: faire surgir, reconstituer, restaurer, au terme de la transmutation à laquelle vous les aurez soumis, Simon, les corps du lexique, les mots entiers, articulés et lisibles, les phrases avec leur sens. à moins que nous ne donnions cet ordre, sans trop y croire, à tout lecteur possible. Voilà peut-être ce que voudraient dire vos titres La Connaissance des textes. Lecture d'un manuscrit illisible ou encore, dirais-je, moi, 'le cognassier des manuscrits.'" Postscript (J.D.)

- The book, La Connaissance des textes, could end with the vision of the travaux

transformed into a bounteous textual quince tree, but does not. Instead, Derrida tells us a story about his trip to

Australia in the summer of 1999 (mentioned by Nancy, 31 July 99; 49) and his leaving a diskette with the rough draft of

Le Toucher in the hands of sculptor Elizabeth Presa, who printed out the pages, folded, stitched, and

transformed them into an extraordinary piece, an airy, standing garment resembling a Victorian wedding dress, for her exhibit,

"The Four Horizons of the Page." As one critic comments:

Derrida himself concludes Connaissance by quoting Presa's artist-statement in English on her aim to "construct garments from and for the horizons of the page--east and west, north and south--horizons achieved within a body of language, my language, spoken with my antipodean accent, formed by my antipodean touch" (156). Derrida's constant shifting in and out of French is confirmed by Presa's emphasis on the shift in language from his French to her English, and, within English, from British or American English to English with an "antipodean accent." It is a graceful and fitting end to the book: we are left to imagine Presa's work, which is not reproduced, a further "absorption" of text into art, a further rendering of "touch."Why this book of Derrida's? No sculptor could fail to be intrigued by a study of touch, for touch is what a sculptor knows intimately when making a work and what a philosopher usually declares to be out of order if one is to talk about art, not the material of art. And why the typescript of his book and not the book itself? Because it contains traces of Derrida's touch that are silently erased in Galilée's handsome production. Here a finger lingers for a moment too long on a key, producing an additional "s" on a word, while just there one notices two words run together in a moment of excited typing. So something of Derrida is folded into these sculptures . . . (Hart, "Horizons and Folds")

Postscript (J.H.)

- Another fruit from the quince tree: two centuries before the Nancy-Hantaï exchange, another

correspondence took place between a philosopher and an artist, between Denis Diderot (named in Le Toucher as one

of Nancy's "predecessors" in the history of "touch" [159, 161, 246], but also, we should note, a thinker of relationality,

rapports) and Etienne-Maurice Falconet. In his final letter to the sculptor, Diderot writes:

We are where we think we are; neither time nor distance has any effect. Even now you are beside me; I see you, I converse with you; I love you. And when you read this letter, will you feel your body? Will you remember that you are in Saint Petersburg? No, you will touch me. I will be in you, just as now you are in me. For, after all, whether something exists beyond us or nothing at all, it's we who perceive ourselves, and we perceive ourselves only; we are the entire universe. True or false, I like this system that allows me to identify with everything I hold dear. Of course I know how to take leave of it when need be. (Oeuvres 15:236) ¤

"Nous sommes où nous pensons être; ni le temps ni les distances n'y font rien. A présent vous êtes à côté de moi; je vous vois, je vous entretiens; je vous aime. Et lorsque vous lirez cette lettre sentirez-vous votre corps? Songerez-vous que vous êtes à Petersbourg? Non, vous me toucherez. Je serai en vous, comme à présent vous êtes en moi. Car, après tout, qu'il y ait hors de nous quelque chose ou rien; c'est toujours nous qui nous apercevons, et nous n'apercevons jamais que nous; nous sommes l'univers entier. Vrai ou faux; j'aime ce système qui m'identifie avec tout ce qui m'est cher. Je sais bien m'en départir dans l'occasion." --A Paris 10bre 1766. Department of Modern Languages and Literatures

University of Richmond

jhayes@richmond.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT (c) 2003 Julie Candler Hayes. READERS MAY USE PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTIONS MAY USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE. FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO PROJECT MUSE, THE ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

I would like to thank Stephen Melville, Michael Newman, and Gary Shapiro for their questions and comments on an earlier version of this piece. I am also grateful to Joanna Delorme for her kind assistance with the images from La Connaissance des textes, which are reproduced courtesy of Editions Galilée.

1. Letter of 9 July 1999 (Connaissance 27; further references will appear with date and/or page number only). Hantaï similarly spoke of pliage as a "solution" to a problem in an interview published in 1973:

2. On Hantaï's career, see Melville, "Simon Hantaï" (112-18); on his influence on French painting in the late twentieth-century, see Pacquement, (Melville, ed. 209-15).An interrogation of gesture becomes necessary. The problem was: how to defeat the privilege of talent, or art, etc...? How to make the exceptional, banal? How to become exceptionally banal? Folding was one way of resolving the problem. Folding came out of nothing. You simply had to put yourself in the place of those who had never seen anything; put yourself in the canvas. You could fill a folded canvas without knowing where the edge was. You have no idea where it will stop. You could go even further and paint with your eyes closed. (Bonnefoi 23-24) ¤

"Il y a une interrogation sur le geste qui s'impose. Le problème était: comment vaincre le privilège du talent, de l'art, etc....? Comment banaliser l'exceptionnel? Comment devenir exceptionnellement banal? Le pliage était une manière de résoudre ce problème. Le pliage ne procédait de rien. Il fallait simplement se mettre dans l'état de ceux qui n'ont encore rien vu; se mettre dans la toile. On pouvait remplir la toile pliée sans savoir où était le bord. On ne sait plus alors où cela s'arrête. On pouvait même aller plus loin et peindre les yeux fermés." 3. See Parent's discussion of Hantaï's "denial of painterly proficiency" in terms of Barthes's essay on the death of the author.

4. Translator's note. Travaux de lecture: literally, "works"--in the sense of "physical work," rather than "work of art" or oeuvre d'art--"of reading." Large construction projects may be spoken of as travaux.

5. A larger section of the same piece appears near the end of the Le Toucher (344-45). Other folded travaux appear 24-25, 152-53, 296-97.

6. Working at set hours, day by day, over the course of an entire year, Hantaï covered the enormous smooth white surface of the work with the liturgical texts associated with the church calendar, as well as philosophical texts, overwritten to illegibility, punctuated by a few significant iconic symbols, a dense and mesmerizing work. Pacquement: "During this period of interrogation into the foundations of pictorial practice, a whole ensemble of processes emerge tending toward the disappearance of mastery, the refusal of the authority of gesture, and resulting in a slowing down of the hand, in effacement" (Melville, ed. 212). See also Baldassari 11-16. Ecriture rose now hangs in the permanent collection of the Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou. A small-scale image (too small, unfortunately, for the handwriting to appear as anything other than a translucent blur) may be seen on the museum's web site <http://www.centrepompidou.fr>. (Click "rechercher" and search under artist = hantai.) Several others of Hantaï's works appear here as well.

7. Hantaï indicates that he intends to copy Donner le temps 203-06, including all or part of the notes, and Etre singulier pluriel 118-19 and part of 120, including footnotes (43). He later indicates that in practice he deviated from this plan to some extent (101); the name "Marx" appearing prominently in one detail (41) would seem to confirm this, as it does not occur within the passages originally specified.

8. Derrida discusses the "rethinking of 'with'" in Etre singulier pluriel in juxtaposition with Merleau-Ponty's notion of "coincidence" in Le Toucher, 224-26.

9. Derrida: "Ici s'imposerait une relecture de La Parole d'Anaximandre" (Donner le temps 201n.); Nancy envisions a more sweeping program: "Il faut réécrire Sein und Zeit . . . c'est la nécessité des oeuvres majeures" (Etre singulier 118n.).

10. Elsewhere: "I tried to say a few words, suspended, about the differences that appeared at that stage between the two texts. But I would tell you nothing new" ¤

(15-19 Sept. 99; 75); later he speaks of the "increasingly abyssal differences between the two texts that appeared during the stretch of time of the copying" ¤"J'essayais de vous dire quelques mots, suspendu, sur les différences apparues à cette étape entre les deux textes. Mais je ne vous apprendrai rien" (28 Nov-17 Dec 99; 95)."différences de plus en plus abyssales entre les deux textes, apparues par l'étalement dans le temps de ces copies"

11. Nancy's vocabulary in Etre singulier pluriel and his recurring use of the term "exposure" (s'exposer, exposition) suggest an implicit dialogue with the work of Emmanuel Lévinas, particularly Autrement qu'être, which Nancy salutes in a note as "exemplary" (Etre singulier 52n.) but does not discuss further per se. In Le Toucher, Derrida refers to "deux pensées de substitution" in Lévinas and Nancy (292), but his primary reference is to Lévinas's Totalité et infinite, rather than the central chapter on "substitution" in Autrement qu'être.

12. See also Deleuze's more extended comparison, Le Pli 50-51. Deleuze also mentions Hantaï in Pourparlers 211. (I thank Charles J. Stivale for this reference.)

13. Pacquement: "Hantaï's painting . . . is not structured in a finalized history, or at any rate, that history remains to be written. There are entire layers (pans) of his work that remain to be discovered, as if the foldings had literally veiled certain parts; or as if the observation of the work, inscribed in a much too linear structure, had sidestepped moments of consequence that remained invisible merely for lack of someone's eye chancing upon them" (Melville, ed. 210).

14. On historical and methodological questions, see Bossis and Altman (as well as a number of the other articles in the same volume). For a range of contemporary theoretical approaches to the reading of "real" correspondences, see Kaufmann, Melançon, and Abiteboul. Chamayou offers a consideration of epistolarity, real and fictional, that is also sensitive to issues of historicity (see esp. 161-82).

15. See Hayes, "The Epistolary Machine," Reading the French Enlightenment 58-85. As the phrasing suggests, the model follows the general lines of the "desiring machines" described in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, L'Anti-Oedipe 43-50.

16. See also Nancy's critique of the notion of desire as lack, L''il y a' du rapport sexuel (36-37).

17. As an editorial footnote--that staple of epistolary novels--helpfully informs us, "we have retained the letters exchanged just before the beginning of the project of the 'travaux de lecture'"¤

(13n.). As there is no reason given for this decision, one tends to agree with Derrida that Hantaï's evocation of bucolic life ("regardant les enfants et 'l'herbe pousser") provides the ideal literary setting, "l'installation discrète mais savante d'un décor," for the text to follow (Connaissance 148)."On a gardé les quelques lettres échangées peu avant le début du projet des 'travaux de lecture'" 18. The ongoing references to the bodily states of the two interlocutors create a background music of concern and intimacy. "How is your health, now? I wanted to ask and didn't dare," ¤

writes Hantaï in one of his earliest letters (21). The word "maintenant" underscores a recognition of Nancy's ongoing struggles. Later, Hantaï's wife Zsuzsa, whose health is also a subject of concern, reads L'Intrus, Nancy's account of his heart transplant (15-19 Sept; 75). In his afterword, Derrida is unable to resist a reference to the memoir: "l'intrus, c'est moi" (155). In Le Toucher, he returns to L'Intrus and Nancy's operation on a number of occasions in passages that bespeak both philosophical engagement and friendship (Toucher 113-15, 301, 308-9). See in particular a note on gratitude and "the heart" and evoking a "souvenir presque secret" of a phone conversation between the two held the day preceding the operation (Toucher 135n.)."Comment va votre santé, maintenant? Je voulais et n'osais vous le demander" 19. Others have wanted to "do something" with Hantaï's letters. His lapidary style tends to appear in many of the texts written about him, as if in echo of earlier written or conversational exchanges. A series of letters written from the painter to critic Georges Didi-Huberman between February 1997 and January 1998, was published in the catalog for the major Hantaï retrospective held in Münster in 1999; they have been translated into English and included in As Painting (Melville 216-29). Accompanied by many photographs, but missing Didi-Huberman's replies, these letters suggest less a "correspondence" than a set of programmatic statements by the artist.

20. Hantaï's altered consciousness via work on the travaux is reminiscent of the impersonal, quasi-meditative execution of Ecriture rose, which critics have likened to "spiritual exercises" (Baldassari 11-16; see also Didi-Huberman, 32-6). In his essay for Hantaï's Biennale catalog, Yves Michaud describes Ecriture rose in terms that apply equally well to the travaux: "Here all the elements count: not only the forgetting of self implied by the infinite copy, but also the manner of confiding in others, abandoning oneself to others, implied in making others' discourse one's own.... The same manner of forgetting oneself, silencing oneself, acceding to a full silence" (16). ¤

"Ici tous les éléments comptent: non seulement l'oubli de soi qu'implique la copie infinie . . . mais tout autant la manière de se confier à autrui, de s'abandonner à autrui, qu'implique le fait de faire sien son discours. . . . Même manière de s'oublier et de se faire taire, d'accéder à un silence plein" 21. A thematics of blindness runs through Connaissance, beginning with Hantaï's reference to a Hungarian proverb, "Bêche ses yeux" (33), his musings on a possible contribution to the "haptic-optic debate" (85), and so on to his dismissal of one of Nancy's more ambitious ideas for publishing the letters as "Un an ou deux de travail de poudre aux yeux" (137). The question of blindness extends deep into Hantaï's career, where it is intimately related to his notions of the hand and of "folding as method." As Dominique Fourcade wrote for Hantaï's 1976 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou: "How far we have come from the time of Matisse, when it was just a question of cutting out the tongue! The problem is having nothing left in one's hands, having to paint with hands behind the back. It seems to be a question of painting with your eyes put out" (n.p.). ¤

"Comme il est loin, le temps de Matisse où il ne s'agissait que de se couper la langue! Le problème est de ne plus rien avoir dans les mains, de se mettre dans les conditions de peindre les mains attachées derrière le dos. La question serait de peindre les yeux crevés" 22. "One can only touch a surface, that is a skin or the covering of a limit (the expression, 'to touch the limit' returns irresistably, like a leitmotiv, in many of Nancy's texts that we will examine). But a limit, limit itself, by definition, seems deprived of a body. It cannot be touched, will not let itself be touched, it eludes the touch of those who either never attain it or forever transgress it" (Derrida, Le Toucher 16). ¤